An Introduction to Photos from Below

by

Fergus Lamb

October 11, 2024

Featured in Photos from Below (Book)

An introduction to the Photos from Below project.

theory

An Introduction to Photos from Below

by

Fergus Lamb

/

Oct. 11, 2024

in

Photos from Below

(Book)

An introduction to the Photos from Below project.

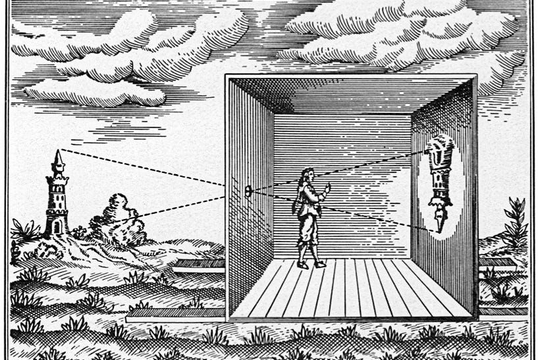

Do workers and bosses see the world in the same way? For the Worker’s Photography Movement - the name given to the various left wing photography clubs which sprang up across Europe and elsewhere in the 1920s and 30s - the answer was no. Whilst everyone perceives the same world, the way that they do so, the emphasises that they place on different aspects, differ. This adds up to the existence of class-based perception. Worker photographers weren’t concerned with shying away from this fact, but instead with developing it. Supported by various communist parties, worker’s photography clubs distributed cameras, technical know-how and access to darkrooms amongst the working class. Left-wing magazines - like the Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (or Worker’s Illustrated Magazine) in Germany - cultivated relationships with worker-photographer correspondents after they realised that the photographs made available by the bourgeois press weren’t appropriate for their projects. Before technological developments in the latter half of the century made cameras more widely available, the working classes rarely saw their lives depicted in the new medium, and if they did, the images were taken by members of the bourgeois class. The principle of the Worker’s Photography Movement was that only the working class could document their own lives. What was worked towards was the construction of a visual class consciousness i.e., the development of a specifically working-class way of seeing the world, distinguished from the capitalist way of seeing. This was achieved by seizing the most advanced means of representation - the camera.

Today, many of the technical difficulties faced by the Worker’s Photography Movement have been overcome. Nearly every worker carries a high quality camera in their pocket. In a sense, the capacity to make photos has been democratised. But does this mean that we take photographs as workers? One of the lessons of the Worker’s Photography Movement is that we have to learn to see the world from the perspective of our class. In his 1930 essay ‘The Worker’s Eye’, Edwin Hoernle wrote that, although the worker and the boss do see the world in distinct ways, the worker photographer has to develop this distinction, to learn to photograph proletarian reality ‘in a hard, merciless light.’ Doing so, Hoernle believed, would ‘increase the fighting power of our class in so far as our pictures show class consciousness, mass consciousness, discipline, solidarity, a spirit of aggression and revenge.’ It was for the same reason that the German communist Hermann Leupold would declare the camera, ‘a weapon in the class struggle’. Today, the task is to re-learn how to wield it.

This is where Photos from Below comes in. It is a new project from the Notes from Below collective, which aims to develop our ability to see the world from the perspective of our class. To do so, we’re looking for workers to submit photographs of their work.

This project can be thought of as a visual wing of the worker’s inquiry revival. For us, worker’s inquiry is the essential basis for class struggle. Strategy must be grounded in the lived reality of the working class because of the worker’s privileged position within the capitalist system. This is why we platform the voices, experiences - and now photographs - of workers. Photos from Below is an experiment aimed at discovering what contemporary work looks like from the perspective of those who perform it. To the slogan of worker’s inquiry - ‘No Politics Without Inquiry!’ - we can add a slogan taken from Hoernle’s essay: ‘No camera without a proletarian eye behind it!’

Why photograph work?

One way of answering this is to highlight why it benefits capitalism that we don’t photograph work. There are two key reasons. Firstly, because when the majority of people don’t see the work that goes into producing a given good, it allows the business which sells that good to present it as something which it - rather than the workers - made. And secondly, because the ‘hiddenness’ of production also hides from view the exploitative working practices which capitalists use to drive up their profits. This is why, in Capital, Marx’s attempt to reveal the ‘secret of profit making’ necessitates that he must follow the worker into what he calls ‘the hidden abode of production’ - the workplace. Here, profit is revealed as the exploitation of the worker. This entails a shift in perspective, for it is only from the position of the worker that the truth of the capitalist system can be grasped.

Another reason to photograph work is because what work looks like has undergone dramatic changes in recent decades. The image of labour and workers produced by the first worker’s photography movement - which often centred male, able-bodied factory workers - doesn’t necessarily map onto contemporary labour. Technological changes, such as that lie behind the rise of ‘gig economy’ jobs, alongside changes in class composition, necessitate an updated visual language of work. A new program of worker’s photography provides the opportunity to renew our imagination of what work looks like.

What are we looking for?

If you work – and if it’s safe for you to do so – we want you to photograph your work.

It’s up to you to decide what your photos look like - they can be in colour or black and white, pretty or ugly. They can be taken on a film camera or on a mobile phone. If you want to, you can use the technique of ‘staging’ photos, instead of relying on more traditionally ‘documentary’ methods (i.e., taking a photo of exactly what you see at work). You might also want to consider ordering your photos in a sequence, or adding a caption to each image. Try and find a way to photograph your work in a way that shows it in ‘a hard, merciless light’ - i.e., how it really is.

Featured in Photos from Below (Book)

author

Fergus Lamb

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Institution of Autonomy: The Worker Photography Movement

by

Steve Edwards

/

Oct. 11, 2024