Karl Marx - Instructions for the Delegates of the Provisional General Council and The Different Questions (1866)

by

Karl Marx

July 9, 2022

Featured in Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry (#14)

Chapter Two

theory

Karl Marx - Instructions for the Delegates of the Provisional General Council and The Different Questions (1866)

by

Karl Marx

/

July 9, 2022

in

Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry

(#14)

Chapter Two

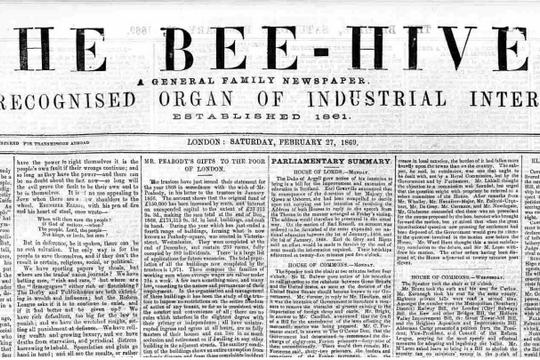

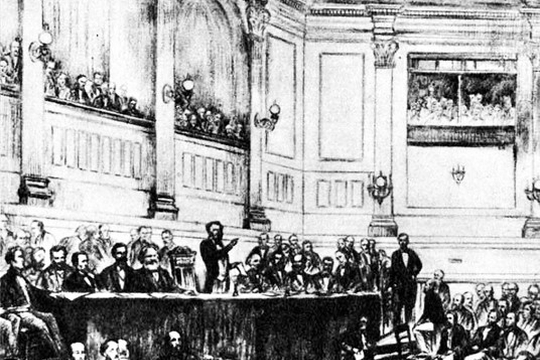

These instructions, written by Marx in August 1866, were submitted to the First General Congress of the International Working Men’s Association (IWMA), held in Geneva in September of that year. They were first published in English in the newspaper The International Courier, in February 1867. The Geneva Congress represented a pivotal moment for the IWMA, establishing the revolutionary character of the Association and its focus on class-struggle and worker organising. The Association adopted almost all of Marx’s proposals, including his call for international workers’ inquiries, reproduced below, which was accepted unanimously. Marx’s instructions on trade unions, the limitation of the working day, and the Polish national question are also included here, relevant as they are to the history outlined in this volume. Original footnotes from the Marx-Engels Collected Works (MECW) version have also been included in this abridged reproduction.

Organisation of the International Association

Upon the whole, the Provisional Central Council recommend the plan of Organisation as traced in the Provisional Statutes. Its soundness and facilities of adaptation to different countries without prejudice to unity of action have been proved by two years’ experience. For the next year we recommend London as the seat of the Central Council, the Continental situation looking unfavourable for change.

The members of the Central Council will of course be elected by Congress (5 of the Provisional Statutes) with power to add to their number.

The General Secretary to be chosen by Congress for one year and to be the only paid officer of the Association. We propose £2 for his weekly salary.1

The uniform annual contribution of each individual member of the Association to be one half penny (perhaps one penny). The cost price of cards of membership (carnets) to be charged extra.

While calling upon the members of the Association to form benefit societies and connect them by an international link, we leave the initiation of this question (etablissement des societes de secours mutuels. Appoi moral et materiel accorde aux orphelins de l’association)2 to the Swiss who originally proposed it at the conference of September last.

International combination of efforts, by the agency of the association, in the struggle between labour and capital

(a) From a general point of view, this question embraces the whole activity of the International Association which aims at combining and generalising the till now disconnected efforts for emancipation by the working classes in different countries.

(b) To counteract the intrigues of capitalists always ready, in cases of strikes and lockouts, to misuse the foreign workman as a tool against the native workman, is one of the particular functions which our Society has hitherto performed with success. It is one of the great purposes of the Association to make the workmen of different countries not only feel but act as brethren and comrades in the army of emancipation.

(c) One great “International combination of efforts” which we suggest is a statistical inquiry into the situation of the working classes of all countries to be instituted by the working classes themselves. To act with any success, the materials to be acted upon must be known. By initiating so great a work, the workmen will prove their ability to take their own fate into their own hands. We propose therefore:

That in each locality, where branches of our Association exist, the work be immediately commenced, and evidence collected on the different points specified in the subjoined scheme of inquiry.

That the Congress invite all workmen of Europe and the United States of America to collaborate in gathering the elements of the statistics of the working class; that reports and evidence be forwarded to the Central Council. That the Central Council elaborate them into a general report, adding the evidence as an appendix.

That this report together with its appendix be laid before the next annual Congress, and after having received its sanction, be printed at the expense of the Association.

General Scheme of Inquiry, which may of course be modified by each Locality

- Industry, name of.

- Age and sex of the employed.

- Number of the employed.

- Salaries and wages: (a) apprentices; (b) wages by the day or piece work; scale paid by middlemen. Weekly, yearly average.

- (a) Hours of work in factories. (b) The hours of work with small employers and in home work, if the business be carried on in those different modes. (c) Nightwork and daywork.

- Meal times and treatment.

- Sort of workshop and work: overcrowding, defective ventilation, want of sunlight, use of gaslight. Cleanliness, etc.

- Nature of occupation.

- Effect of employment upon the physical condition.

- Moral condition. Education.

- State of trade: whether season trade, or more or less uniformly distributed over year, whether greatly fluctuating, whether exposed to foreign competition, whether destined principally for home or foreign competition, etc.3

Limitation of the Working Day

A preliminary condition, without which all further attempts at improvement and emancipation must prove abortive, is the limitation of the working day. It is needed to restore the health and physical energies of the working class, that is, the great body of every nation, as well as to secure them the possibility of intellectual development, sociable intercourse, social and political action. We propose 8 hours work as the legal limit of the working day. This limitation being generally claimed by the workmen of the United States of America,4 the vote of the Congress will raise it to the common platform of the working classes all over the world. For the information of continental members, whose experience of factory law is comparatively short-dated, we add that all legal restrictions will fail and be broken through by Capital if the period of the day during which the 8 working hours must be taken, be not fixed. The length of that period ought to be determined by the 8 working hours and the additional pauses for meals. For instance, if the different interruptions for meals amount to one hour, the legal period of the day ought to embrace 9 hours, say from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., or from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., etc. Nightwork to be but exceptionally permitted, in trades or branches of trades specified by law. The tendency must be to suppress all nightwork.

Trades’ unions. Their past, present and future

(a) Their past.

Capital is concentrated social force, while the workman has only to dispose of his working force. The contract between capital and labour can therefore never be struck on equitable terms, equitable even in the sense of a society which places the ownership of the material means of life and labour on one side and the vital productive energies on the opposite side. The only social power of the workmen is their number. The force of numbers, however is broken by disunion. The disunion of the workmen is created and perpetuated by their unavoidable competition among themselves.

Trades’ Unions originally sprang up from the spontaneous attempts of workmen at removing or at least checking that competition, in order to conquer such terms of contract as might raise them at least above the condition of mere slaves. The immediate object of Trades’ Unions was therefore confined to everyday necessities, to expediences for the obstruction of the incessant encroachments of capital, in one word, to questions of wages and time of labour. This activity of the Trades’ Unions is not only legitimate, it is necessary. It cannot be dispensed with so long as the present system of production lasts. On the contrary, it must be generalised by the formation and the combination of Trades’ Unions throughout all countries. On the other hand, unconsciously to themselves, the Trades’ Unions were forming centres of organisation of the working class, as the mediaeval municipalities and communes did for the middle class. If the Trades’ Unions are required for the guerilla fights between capital and labour, they are still more important as organised agencies for superseding the very system of wages labour and capital rule.

(b) Their present.

Too exclusively bent upon the local and immediate struggles with capital, the Trades’ Unions have not yet fully understood their power of acting against the system of wages slavery itself. They therefore kept too much aloof from general social and political movements. Of late, however, they seem to awaken to some sense of their great historical mission, as appears, for instance, from their participation, in England, in the recent political movement, from the enlarged views taken of their function in the United States, and from the following resolution passed at the recent great conference of Trades’ delegates at Sheffield:

“That this Conference, fully appreciating the efforts made by the International Association to unite in one common bond of brotherhood the working men of all countries, most earnestly recommend to the various societies here represented, the advisability of becoming affiliated to that body, believing that it is essential to the progress and prosperity of the entire working community.”

(c) Their future.

Apart from their original purposes, they must now learn to act deliberately as organising centres of the working class in the broad interest of its complete emancipation. They must aid every social and political movement tending in that direction. Considering themselves and acting as the champions and representatives of the whole working class, they cannot fail to enlist the non-society men into their ranks. They must look carefully after the interests of the worst paid trades, such as the agricultural labourers, rendered powerless5 by exceptional circumstances. They must convince the world at large6 that their efforts, far from being narrow – and selfish, aim at the emancipation of the downtrodden millions.

Polish question7

(a) Why do the workmen of Europe take up this question? In the first instance, because the middle-class writers and agitators conspire to suppress it, although they patronise all sorts of nationalities, on the Continent, even Ireland. Whence this reticence? Because both, aristocrats and bourgeois, look upon the dark Asiatic power in the background as a last resource against the advancing tide of working class ascendancy; That power can only be effectually put down by the restoration of Poland upon a democratic basis.

(b) In the present changed state of central Europe, and especially Germany, it is more than ever necessary to have a democratic Poland. Without it, Germany will become the outwork of the Holy Alliance, with it, the co-operator with republican France. The working-class movement will continuously be interrupted, checked, and retarded, until this great European question be set at rest.

(c) It is especially the duty of the German working class to take the initiative in this matter, because Germany is one of the partitioners of Poland.

-

In the French text the following paragraph has been added: “The Standing Committee, which is in fact an executive of the Central Council, to be chosen by Congress, the function of any of its member to be defined by the Central Council.” The same paragraph is given in the German text - Ed. ↩

-

Foundation of benefit societies; moral and material assistance to the Association’s orphans. - Ed. ↩

-

The Minute Book of the General Council has “consumption” instead of “competition.” - Ed. ↩

-

When the Civil War ended, the movement for the legislative introduction of an eight-hour working day intensified in the USA. Leagues of struggle for the eight-hour day were set up all over the country. The National Labor Union declared at its inaugural convention in Baltimore in August 1866 that the demand for the eight-hour day was an indispensable condition for the emancipation of labour. ↩

-

The French text here reads: “incapable of organised resistance” - Ed. ↩

-

The French and German texts read: “convince the broad masses of workers” - Ed. ↩

-

The French reads: “Necessity of annihilating Russian influence in Europe by implementing the right of nations to self-determination and restoring Poland on a democratic and social basis.” The German has a similar subtitle in slightly altered wording - Ed. ↩

Featured in Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry (#14)

author

Karl Marx

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?