Political Economy of Hospitality

by

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1),

George Briley (@GeoSBriles)

August 21, 2024

Featured in Shift Patterns (#21)

George and Callum critically examine the state of the British hospitality industry, exploring its profound challenges and systemic issues.

theory

Political Economy of Hospitality

George and Callum critically examine the state of the British hospitality industry, exploring its profound challenges and systemic issues.

Inside the hangar-like halls of the ExCeL centre, managers were circling. It was the first day of The Pub Show 2024, and they had gathered to discuss the future of their industry. The authors were also in attendance, hoping to understand exactly how they plan on adapting their industry to face a radically destabilised future.

The short answer is: they don’t have a clue. They talked a lot about customers, and relatively little about workers. What attention they did pay to workers mostly consisted of complaints: “lots of our new hires,” opined one HR professional, “don’t know what it means to be a good employee, or even what seems to us like basic discipline.” Panels on the mental health crisis amongst the hospitality workforce were staffed by charity bosses who skillfully avoided mentioning any of the key factors behind that crisis (sexual harassment, wages, rents, alienation…) and pub landlords who repeated the glibbest cliches (“working class fathers,” we learned, “don’t know how to talk about feelings.”) Presentations on the future of the industry were mired in the jargon of ‘dwell time’, ‘premium service culture’ and ‘the sustainability journey.’ But sometimes, in the quiet that settled in the gap between another pair of idiotic sentences, you could hear the echo of a worldview.

On the surface, the narrative was that it had been a freakishly bad few years. A random pandemic had distorted demand and labour markets, completely inexplicable events had led to a rise in food and energy costs, and mystical factors had left their workforces depleted and depressed. But, they reassured themselves, everything was going back to normal now. They would double down on upselling and “premiumisation”, get better at highlighting how they were going green to the customer, and use AI to simplify their labour management. The industry, they hoped, was on the verge of bigger and brighter things. But it was hard to avoid the feeling that this confidence was only skin deep. The narrative served to repress and deny the evident truth: hospitality is fucked. Behind every middle manager lurked the spectres of inflation, insubordinate labour power, and climate collapse.

What is the reality that the industry is working so hard to repress? In what follows, we will zoom out to consider the coordinates of the contemporary hospitality industry and its future prospects.

From Industry to Services

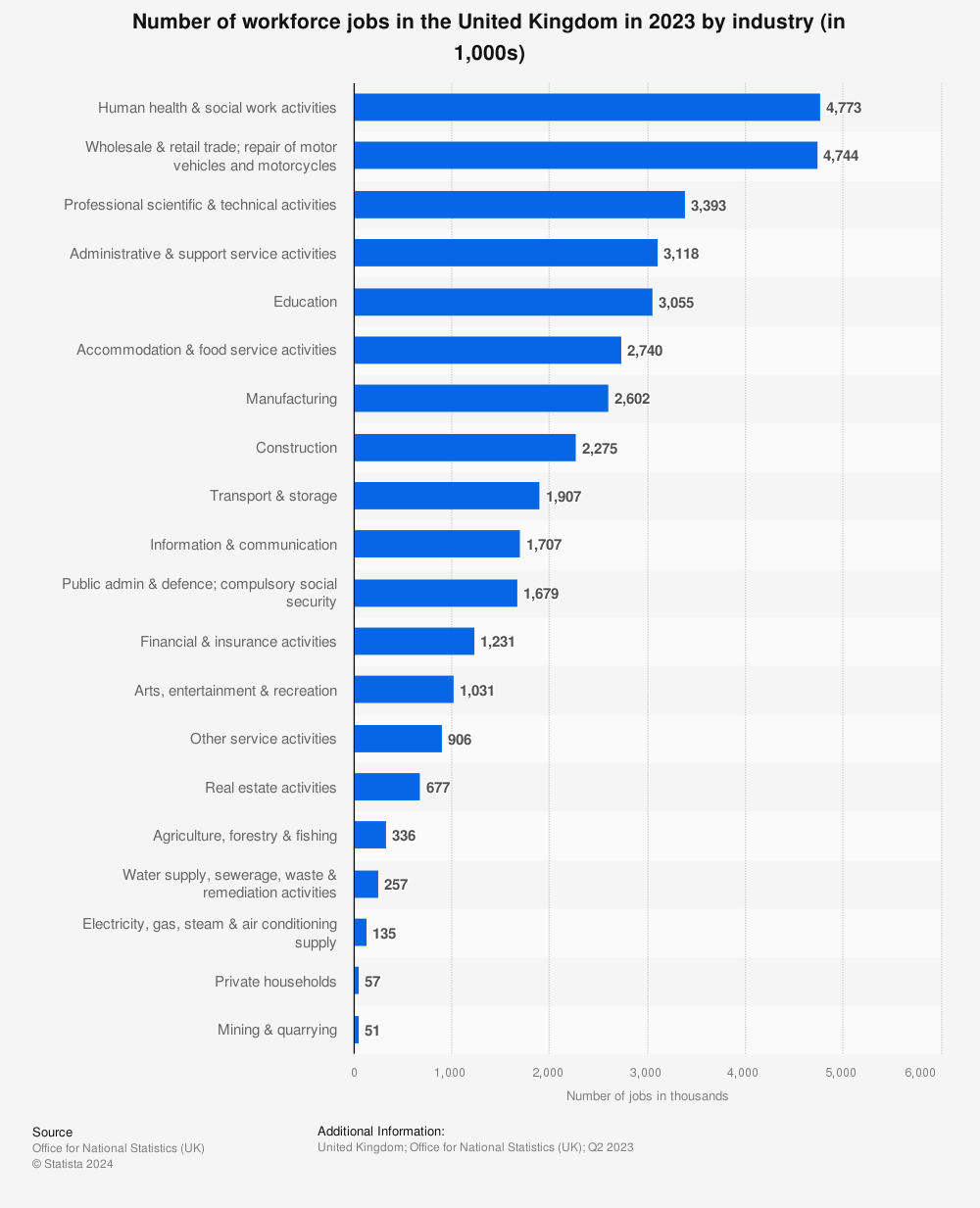

Hospitality is the third largest employer in the UK, with 3.5 million people working in the sector1, making it an incredibly significant part of the economy. We can’t talk about the growth of the hospitality industry without putting it into the larger context of the deindustrialisation of the British economy over the past five decades. The sector doesn’t emerge as a dominant industry and major employer out of nowhere. Deindustrialisation in Britain refers to the decline of the country’s industrial sector, particularly in manufacturing, beginning in the mid-20th century. The political project of breaking up the historic power bases of the working class saw politicians privatise, decimate and offshore British industrial capabilities. It led to significant job losses and economic devastation, particularly in areas heavily reliant on manufacturing, such as the West Midlands, Wales and the North. It means that British hospitality businesses find themselves increasingly reliant on imported products for retail and all the insecurity of global supply chains that comes with that. Quite uniquely in pubs and bars, government intervention into pub ownership by breweries in the early 1990s (called the Beer Orders) has led to an increased focus on retail profits.2 As James Wilt reveals in Drinking Up The Revolution,3 alcohol production is one of the largest global monopolies going, with 6 big companies having a tight grip on production.

The shift away from manufacturing in Britain has seen us increasingly driven towards a service-based economy, from hospitality services to financial services. ONS data4 from 2023 shows the extent of the concentration of employment in the service sector within the Britain economy. This reality challenges the class maps we have inherited from struggles of the past. The major industries through which the labour movement won its historic political victories for the working class have been decimated. This is a significant challenge if we want to rebuild the labour movement. It means organising in sectors that have little-to-no legacy of industrial disputes, and with workforces with meagre union density let alone coverage of bargaining agreements.

We can often think of the hospitality industry as something untouched by technological or managerial development. Where the server pouring our drink or making our food is mostly unchanged from decades past, that their job is caught in a time warp. This projection of the “traditional” within the hospitality industry is inaccurate though. Across the industry, we see an increased centralisation of both capital and labour. This means that huge, often, international companies dominate our high streets. Small businesses are beaten out by larger venues serving a higher turnover of customers, with more and more workers drawn in to staff these larger spaces. This is not to lament the passing of the petit bourgeois shopkeepers and landlords, but to highlight the increasing connection between the labour process of hospitality workers and big capital.

Focusing on the situation of pubs, bars and clubs as an example of the centralisation of labour, ONS data suggests that whilst the overall number of venues is decreasing across the country, revenue and the number of workers is increasing. We can perhaps account for this by looking into the size of the contemporary venues. In 2018 fewer people were employed in venues with less than 10 employees, as compared to 2001, reducing from 176,000 to 103,000, a fall of 41%. Over the same period, all other size categories of venues have seen increases in the number of people employed. Employment in venues with 10 to 24 employees saw increases of 10%. Establishments with 25-49 employees saw a 74% increase in employment. Venues that had 50 or more employees had a 25% increase in employment.5

It isn’t just having an increase in the number of colleagues that has changed for workers though. The centralisation of capital in the sector has also resulted in investment in and introduction of new technologies to try and increase productivity in an industry increasingly reliant on tight retail margins. The most obvious of these technologies are platforms like Uber, Deliveroo, JustEat etc. Not only do these platforms reorganise the work of delivery riders, but they also increasingly affect labour processes across the industry as businesses integrate them into the workplace. Plucky entrepreneurs are even looking to expand the platform model of insecurity and exploitation to servers inside hospitality venues too.6 This is an important reminder that just because workers might have different technical and social compositions, if the work is similar, techniques of managerial control can travel across. After all, the process of delivering food via an app is not all that different from delivering a pint or a plate to a customer, even if the image we have of the type of person doing those jobs is different. Hospitality workers increasingly find themselves working to orders on a screen or ticket, with the process of taking an order mediated by a platform, even within a physical venue, through QR codes and online orders.

The hospitality industry finds itself in an isolated position economically too. Capital in the industry is increasingly at odds with the state, with national trade bodies declaring that “hospitality is being priced out of existence”.7 This anger is not just saved for the government though, with British hospitality trade bodies decrying the inflated costs of the commodities they retail. Hospitality capital is itself fragmented and its interests are levelled against both the British state and other fractions of capital. Hospitality bosses find themselves raging against the government for extra support, with business hammered by the inflated price of the commodities retailed, a general cost of living crisis hitting its customer base slowing down trade, and suffering from a staffing shortage crisis it seems both unable and unwilling to fix.

Whilst the cost of living crisis has seen many people forced to tighten budgets and go out less often, an increasing trend within the hospitality industry has been to move towards more “elite consumption” or, basically, catering more to posh people. As inequality expands, it makes business sense to target people with more money. City centres are steadily becoming playgrounds for the rich, with soulless corporate “destination venues” increasingly taking the place of more locally embedded “community venues”. Alongside this is the notion of “premiumisation”, very popular at The Pub Show, shifting the offering of venues up the price scale. Venues suffering lower footfall are being advised that they need staff members to be trained in upselling in order to pick up the slack of slow trade.

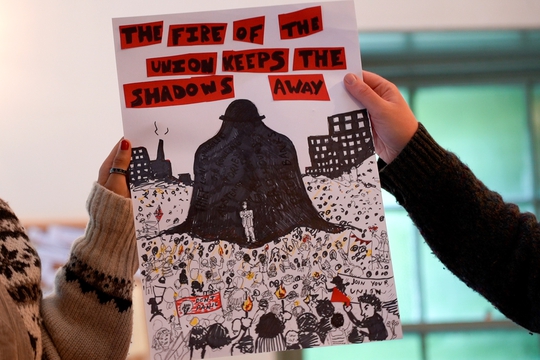

You would think that with the increased centralisation of labour and capital, and increased alienation from venues as community spaces towards hollow relationships with plastic brands, the conditions for labour to organise are fertile. We’ve yet to see organisation emerge en masse though, with the vast majority of workers in the sector not covered by a collective bargaining agreement or even members of a trade union. Whilst there has been some inspiring organising through Unite Hospitality, BFAWU and the IWW, this has not become a national movement. The incredibly impressive organising of Starbucks workers in the US gives a partial view of what this might look like.8 But really, it’s hard to even imagine what a national movement of hospitality worker organisation might look like in Britain, when our class maps from the past give us so little direction or guidance.

Into the Gloomy Future

To understand the factors that will shape class struggle in the hospitality sector in the near future, we need to look at the bigger picture. This moment in the history of capitalism is increasingly defined by one trend: the decline of cheap nature, and with it, the stagnation of living standards.9 It is worth underscoring how new this is. For more than a century, the working class in the global north tended to experience a gradual improvement of material living standards. In Britain after the 1870s, annual real wage rises of 1-3% were the norm.10 When combined with the expanding welfare state and limited political reform, this improvement allowed the ruling class to achieve a seemingly impossible task: the partial stabilisation of capitalism, a system defined by crisis and conflict.

From the late 19th century onwards, Britain’s ruling class benefited from the rising productivity in the factories, imperialist domination in the colonies, a gendered division of labour in the home, and the relentless exploitation of cheap natural resources everywhere. These combined to facilitate a series of different class compositions that successfully subjugated the working class, despite moments of revolutionary potential. Each time the rising costs of natural inputs (principally labour, food, raw materials and energy) began to place limits on accumulation, a combination of geographical expansion, enclosure, and new scientific revolutions opened up a new ecological surplus that could be exploited. These surpluses offered the ruling class room for manoeuvre and allowed it to use working class struggles to drive new processes of development, thereby cutting off routes that led towards revolutionary situations. But now in the 21st century, that new surplus isn’t forthcoming - and, in fact, the bills run up through past exploitation are coming due. In the language of Jason Moore, we have witnessed the transition from the accumulation of surplus value to the accumulation of negative value.

The climate is collapsing in front of our eyes. There are a million data points you can lean on to make this point. The one that is stuck in our throat at the moment is this: global temperatures hit 2°C above 1850-1900 levels on four consecutive days in February 2024.11 Sometimes we distrust our own gut reactions to these numbers, so perhaps it’s helpful to demonstrate how dramatic the consensus on the rate of heating now is amongst climate scientists. A poll of first authors on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports recently showed that a majority of respondents under the age of 50 expected the climate to heat by more than 3 degrees celsius by the end of the century. This is especially remarkable since the IPPC is a profoundly conservative institution which has consistently failed to predict the speed of climate collapse.12 The basic ecological reality can’t be contested. The more open question is how this heating will be felt, reacted to, and struggled over. This is the central hinge of our current class composition, the point around which everything else moves.

Cheap nature is a key concept to deploy in our thinking on this question. It helps us see the reality behind the widespread perception that the ‘cost of living crisis’ has developed from a one-off shock into a new reality. The persistent inflationary pressures that are stalking the advanced economies are the symptom of a general rise in both the labour-intensity and scarcity of those fundamental resources that enable production (in particular energy, raw materials, food and labour power.) The end of cheap nature has knock-on effects throughout the interconnected networks of capital and labour that structure the global economy. As prices rise, so too does our cost of living (defined as the value of the bundle of commodities that is required to reproduce a worker). Eventually, this forces up the value of labour-power.13

This pressure is resolved in three ways. First, workers who cannot force up their wages have to spend more to cover the basic means of subsistence like food and energy, and less on everything else. Second, workers who already earn around the minimum viable wage can be forced to go below the socially-determined norm of living standards, so that their wages cover less than the value of their labour power. Third, capital can increase wages to account for the rising value of labour power. The first and second options are obviously the generally favoured paths of capital, although the third is sometimes unavoidable for it - particularly if workers are organised and militant, or there is intense labour market competition to hire new people.

We can see evidence of all three options around us. The reduction of working class spending is visible in the consumption statistics: between 2021 and 2023, consumers spent 15% more on basically the same volume of commodities.14 In hospitality specifically, the net percentage of consumers spending less on eating out and drinking in pubs and bars over the last three months has consistently risen since April 2021, reaching 16.6% and 19.5% respectively in March 2024.15 These workers are experiencing a more or less gradual reduction in their consumption towards a bare minimum standard.

Others, such as food delivery platform workers, are being forced to accept wages that aren’t enough for them to even maintain a basic standard of living. Some workers are more vulnerable to being forced below this level than others, as the state and capital collaborate to create and mobilise differences between workers (via borders, the welfare system, racist/sexist policing, housing, degrees of employment security/formality, etc.) in order to create populations that can be subjected to this specific form of exploitation.

Finally, other workers are forcing higher wages through collective action or moving between employers/industries to find higher pay. These tend to be those workers who have access to significant collective or individual bargaining power. As the evidence of consumption data shows, however, it is the first option which predominates. A social composition of the working class defined by the capacity of cheap nature to facilitate consistently rising living standards in the advanced economies has been falling apart for a long time: at least since the crisis of 2007-8. But now this process is picking up speed. This trend will fluctuate, but the direction of travel seems set. Cheap nature enabled a specific kind of class compromise which is coming to an end - what comes next is an open question.

The decomposition of the old settlement, however, does not only matter when we think about how workers reproduce themselves. It is also a major pressure that shapes the way that workers in certain industries are organised by capital into a working class. This is true in any industry where:

- Labour is a major cost and the opportunities for productivity gains are limited (in Marx’s terms, where the organic composition of capital is low and likely to remain low)

- Other once cheap ‘natural’ inputs (food, energy, raw materials) are fundamental to the production process

- Working class consumers make up a significant proportion of the market for the commodities produced by the industry, but these commodities are not necessarily part of the means of subsistence and demand can be reduced if budgets are squeezed

In these industries, the factors of production are becoming more expensive at the same time as the market for commodities shrinks (due to the reallocation of working class consumption to the essential means of subsistence). The result is a sharp reduction in the rate of surplus value extraction at the same time as a contraction in the wider market leads to overproduction.

Hospitality is perhaps the perfect example of an industry caught in this pinch. Capital in the hospitality industry is particularly prone to being technologically stagnant. The labour processes that produce service commodities like drinks served at a bar or food prepared to a more premium standard, are very difficult to accelerate. As the economist William Baumol famously identified, a string quartet today requires just the same amount of labour to operate as it did in 1800. The provision of certain services is very resistant to change due to the nature of the service itself. In hospitality, the tools and techniques of industrialisation can be applied to segments of the sector (e.g. food production) up to a point. For instance, fast food kitchens are quasi-industrial in their organisation, although their spatial distribution and ownership models usually impose upper limits on the introduction of fixed capital. But in other parts of the industry (restaurants, cafes, hotels) productivity gains are hard to come by. Wild dreams of automated food production and delivery via robotics appear to be significantly beyond even the largest and best-funded businesses in the industry. This is not to say that there are no ongoing attempts to introduce technology in these workplaces, but that they cannot, in their current form and at their current scale, fix the crisis of profitability in the sector.

The other two factors described above are relatively self-evident: food, energy and wages are all fundamental inputs to every business in the industry and cannot be easily substituted for alternatives. Mass consumption hospitality businesses rely on working class budgets extending to cover non-essential services: they are the businesses that sell us roses, rather than bread.16

Capital in the industry seems to be in denial over the impending squeeze. But even if there are discussions about this near-future scenario in boardrooms, the avenues for action seem limited. Labour costs are the factor of production that are most within the control of hospitality capital, and there have been predictable long-term efforts to reduce these costs to the minimum possible level. Work in the industry has been consistently intensified, sometimes through low-tech managerial practices like surveillance, bullying and harassment, and sometimes through the application of digital management technologies. The most prominent examples of these technologies on display at The Pub Show 2024 were AI tools that forecast demand on the basis of past sales volume and worked out what staffing level would allow a business to service the maximum number of customers with the minimum number of workers, deleting workers from shift patterns and intensifying work.

Other technologies that combine various forms of sales and video data in an AI software package that acts as a virtual supervisor seem possible, but have yet to reach widespread deployment and face potentially significant legal and cultural barriers. However, these management methods have major limitations. The result of work intensification is an ever-rising baseline of workplace conflict between managers and a workforce that is predominantly young, concentrated in urban locations, and often has a contradictory but predominantly leftist politics. This resistance is at present expressed mostly via informal means such as euphemistically named ‘turnover’ (leaving), ‘shrinkage’ (nicking) and ‘organisational misbehaviour’ (resisting). An additional impact is the widespread mental health crisis in the hospitality workforce, with various reports of 84% of staff experiencing a mental illness during their careers17 and 85% experiencing symptoms of mental ill health in the past year.18 Attempts to intensify work further will likely produce diminishing returns as they are met with both formal and informal worker resistance.

So, given the difficulty of squeezing more labour out of the same workers, the major escape routes open for the industry go via the state. Given that wages in the sector are clustered around the minimum wage (either actually at the legal minimum or pegged to a relatively stable percentage above it), the state is the de facto regulator of wages in the industry. The state could, therefore, ‘defend’ the hospitality industry by allowing for a specific minimum wage exemption for certain kinds of employees or businesses. This option, however, would seem likely to prompt significant resistance from workers in the sector. A more realistic hope, from the point of view of hospitality capital, might be for governments to accept longer-term repression of the minimum wage so that its value falls in real terms. Both would mean significant potential damage to a government’s popular support and risk the emergence of wider struggles. A second, less politically toxic avenue for increasing profitability would see the government implement VAT cuts on hospitality commodities. This would be a relatively straight tradeoff between state revenues and industry finances, and therefore has its own significant downsides for a state that is already struggling with fiscal balance. It should come as no surprise that both of these policy options (wage repression and tax cuts) are being more or less publicly advocated for by newly-knighted Wetherspoons boss Tim Martin.

If this sketch of the balance of forces within the industry is accurate, we should be able to validate it with reference to the current state of play. Hospitality businesses would already be showing significant signs of stress, despite the return to in-person leisure following the pandemic. Rather than lockdown being a one-off stress that the industry has bounced back from, overall performance should be showing a more long term decline. And what do we find? Exactly that. After a temporary post-pandemic bump as demand surged, the financial health of the industry has already declined back to 2021 levels.

‘Zombie’ firms are generally defined as indebted companies which can just about remain solvent but cannot meaningfully invest in growth or in reducing their debts. Such firms make up 19% of firms in the hospitality industry, significantly more than the approximately 12.4% of firms in the Britain economy that are either at risk of becoming or have already become zombies.19 Indebtedness in the industry has risen substantially from pre-pandemic levels, with a 37% increase in debt burdens amongst the largest firms with a value of more than £250,000. This comes at a moment when higher interest rates make such a debt burden significantly more expensive, thereby piling on the pressure. Across the industry, there are £4.9 billion more short term liabilities due than there are realisable assets to pay them. The results are predictable, with market analysts suggesting that 47% of firms are facing a significant risk of bankruptcy or restructuring within the next three years. Such a wave of restructuring would mark an acceleration in an existing tendency towards consolidation and centralisation under the control of larger firms. Because whilst many firms are struggling with debt and low profitability, there are others that hold a relatively stronger position within the industry that are ready to occupy the space evacuated by failing businesses. If this centralisation accompanies an overall reduction in employment, then it might mark the emergence of a new kind of deindustrialisation driven by input costs - a phenomenon which would be particularly significant given that services have generally absorbed the massive amounts of labour expelled from manufacturing over the last century.

Far from offering an alternative strategy for capital, the new models of operation which have emerged in hospitality in the last decade are actually barriers to further development. Food delivery platforms in particular have operated on a monopoly-securing strategy that was invented in the era of low interest rates and surplus capital. Now they have grown to a gargantuan size they are proceeding to cannibalise the profits of other fractions of capital through market rents in the form of commission. Platformisation has, at least temporarily, allowed them to ‘solve’ labour costs through the utilisation of migrants without papers working for sub-minimum wages that often fail to cover the means of subsistence. Jason Smith has argued that the two characteristic corporate forms of our conjuncture are the platform and the zombie20 - this precisely describes the dynamics in hospitality. Rather than the platform offering a way out for capital, it instead intensifies the dynamics producing zombies in the first place by using its market power to stake a claim on value produced elsewhere in the industry.

We have now examined at some length the macro impasse facing capital in the hospitality industry. But to understand the real stakes of this discussion, we have to flip this question on its head. What does the end of cheap nature and the faltering accumulation of capital in the industry mean for the millions of workers who allow it to function on a daily basis?

The challenge for hospitality workers is to collectively discover a form of struggle that can respond to the crisis of the industry that employs them. This form cannot be dictated from the outside. Those located in the most industrialised and capital-intensive parts of the sector have the strongest prospects for formal collective bargaining that could defend their wages and conditions. Centralised production and distribution facilities like bakeries and warehouses are the most obvious candidates. Outside of those pinch points, it’s unlikely to be a form of struggle that bargains for a share of value created through increasing productivity, given a state of play characterised by technological stagnation, rising input costs, and wobbly consumer demand. What limited examples we can draw on from the vast network of service locations that are dotted across the British urban landscape seems to suggest that the ongoing concentration of more workers into larger workplaces (which may be further accelerated by the potential collapse of small zombie firms) could create febrile organising environments. In these workplaces, young precarious service workers are placed under huge strain for poverty wages, with little or no prospect of significant improvements in the future through a partnership or class collaborationist model. It is a combustible combination, and the resulting sparks can fly in many different directions, but the potential for the formation of coalitions of urban service workers around wage demands and a different political horizon has manifested at times in the past decade (even if only for short bursts).21

If such a development occurs again at a more sustained level, then the short-term victories won by that organising are likely to run up against soft economic limits that will require political struggle if they’re to be overcome. No worker can ever win the future they deserve within the bounds of the capitalist mode of production - but the barrier is particularly pronounced in an industry where capital accumulation has become so squeezed. This is a question that is being worked out in the everyday reality of the struggle already; just look at the examples from Scotland of new creative cultures of organising and the development of workers cooperatives included elsewhere in this issue.

Class struggle in a collapsing climate will not necessarily look like the class struggle of the past. The exact form it takes, however, can’t be decided on the basis of abstract calculations. As Lenin argued in a discussion of forms of struggle after the 1905 revolution:

Marxism differs from all primitive forms of socialism by not binding the movement to any one particular form of struggle. It recognises the most varied forms of struggle; and it does not “concoct” them, but only generalises, organises, gives conscious expression to those forms of struggle of the revolutionary classes which arise of themselves in the course of the movement. Absolutely hostile to all abstract formulas and to all doctrinaire recipes, Marxism demands an attentive attitude to the mass struggle in progress, which, as the movement develops, as the class-consciousness of the masses grows, as economic and political crises become acute, continually gives rise to new and more varied methods of defence and attack.22

The hospitality sector will have to be one such place where we apply that ‘attentive attitude to the mass struggle in process,’ and workers’ inquiry is the method through which we can apply it. Rather than writing off workers’ capacity to struggle at work because of the suspicion that they are powerless in the face of impersonal forces, we should find the cracks where - against all odds - the proletarian capacity to turn the world on its head begins to make itself felt. Crisis is the condition of business in hospitality, but we have no interest in the defence of a splintering status quo.

-

https://www.ukhospitality.org.uk/media-centre/facts-and-stats/ ↩

-

Mellows, Phil (11 Dec 2019) ‘How the Beer Orders still influence the on-trade 30 years later’, The Morning Advertiser. ↩

-

Wilt, James (2022) Drinking Up the Revolution: How to Smash Big Alcohol and Reclaim Working-Class Joy. London: Repeater Books. ↩

-

Clark, D. (3 Jul 2023) ‘Number of workforce jobs in the United Kingdom in 2023 by industry’, Statista. ↩

-

Foley, Niamh (21 May 2021) ‘Pub Statistics’, UK Parliament ↩

-

Wyer, Sean (16 Sep 2021) ‘A Marathon, Not a Stint’, Eater London. ↩

-

Wholesale Manager (24 Apr 2024) Hospitality groups across UK and Ireland say sector is being priced out of existence ↩

-

Anonymous Starbucks Worker (2023) ‘Get a Job and Organise It’, Notes from Below ↩

-

Cheap nature refers to inputs like labour, food, resources and energy that can be used by capitalists without covering the full costs of their production. See Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life, particularly Part 4: The Rise and Demise of Cheap Nature. ↩

-

Gazeley, Ian (2014) ‘Income and Living Standards, Great Britain 1871-2011’ in The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain. Volume 2: 1870 to the Present, edited by Roderick Floud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩

-

Copernicus Climate Change Service. February 2024 Was Globally the Warmest on Record. ↩

-

The Salvage Collective (2011) The Tragedy of the Worker: Towards the Proletarocene. London: Verso Books. ↩

-

For more on the value of labour power, see chapter six of Marx’s Capital Volume 1: “The value of labour-power is determined, as in the case of every other commodity, by the labour-time necessary for the production, and consequently also the reproduction, of this special article… Therefore the labour-time requisite for the production of labour-power reduces itself to that necessary for the production of those means of subsistence; in other words, the value of labour-power is the value of the means of subsistence necessary for the maintenance of the labourer… the number and extent of his [sic] so-called necessary wants, as also the modes of satisfying them, are themselves the product of historical development, and depend therefore to a great extent on the degree of civilisation of a country, more particularly on the conditions under which, and consequently on the habits and degree of comfort in which, the class of free labourers has been formed.” ↩

-

Romei, Valentina (2 May 2024) UK Households Cut Back on Beer, Meat and Domestic Appliances after Prices Surge’, Financial Times. ↩

-

Sugiura, Eri (29 Apr 2024) ‘Britons Avoid the Pub as Cost of Living Weighs on Leisure Spending’, Financial Times. ↩

-

Hospitality businesses that successfully orientate themselves towards ‘elite consumption’ are likely to prove largely exempt from the analysis presented here, as growing inequality will see the ruling class continue to consume an ever larger volume of services by value. ↩

-

RSPH (2019) Service With(out) a Smile? London: Royal Society for Public Health. ↩

-

Planday (2024) The Shift Towards Retention: How to Reduce Staff Turnover in Britain Hospitality. London: Planday. ↩

-

Statistics in the following paragraph taken from: (2023) Britain Hospitality Sector Report - Finances Are Faltering. London: Opus Business Advisory Group. ↩

-

Smith, Jason E. (2020) Smart Machines and Service Work: Automation in an Age of Stagnation. Field Notes. London: Reaktion Books. ↩

-

Cant, Callum, and Jamie Woodcock (2020) ‘Fast Food Shutdown: From Disorganisation to Action in the Service Sector’, Capital & Class, Vol. 44:4. ↩

-

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich (1906) ‘Guerrilla Warfare’, Proletary. ↩

Featured in Shift Patterns (#21)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Organising Culture in the Hospitality Industry

by

James Barrowman,

Cailean Gallagher

/

Aug. 21, 2024