Post-mortem of a piss-up in a brewery

by

Amardeep Singh Dhillon (@amardeepsinghd)

August 21, 2024

Featured in Shift Patterns (#21)

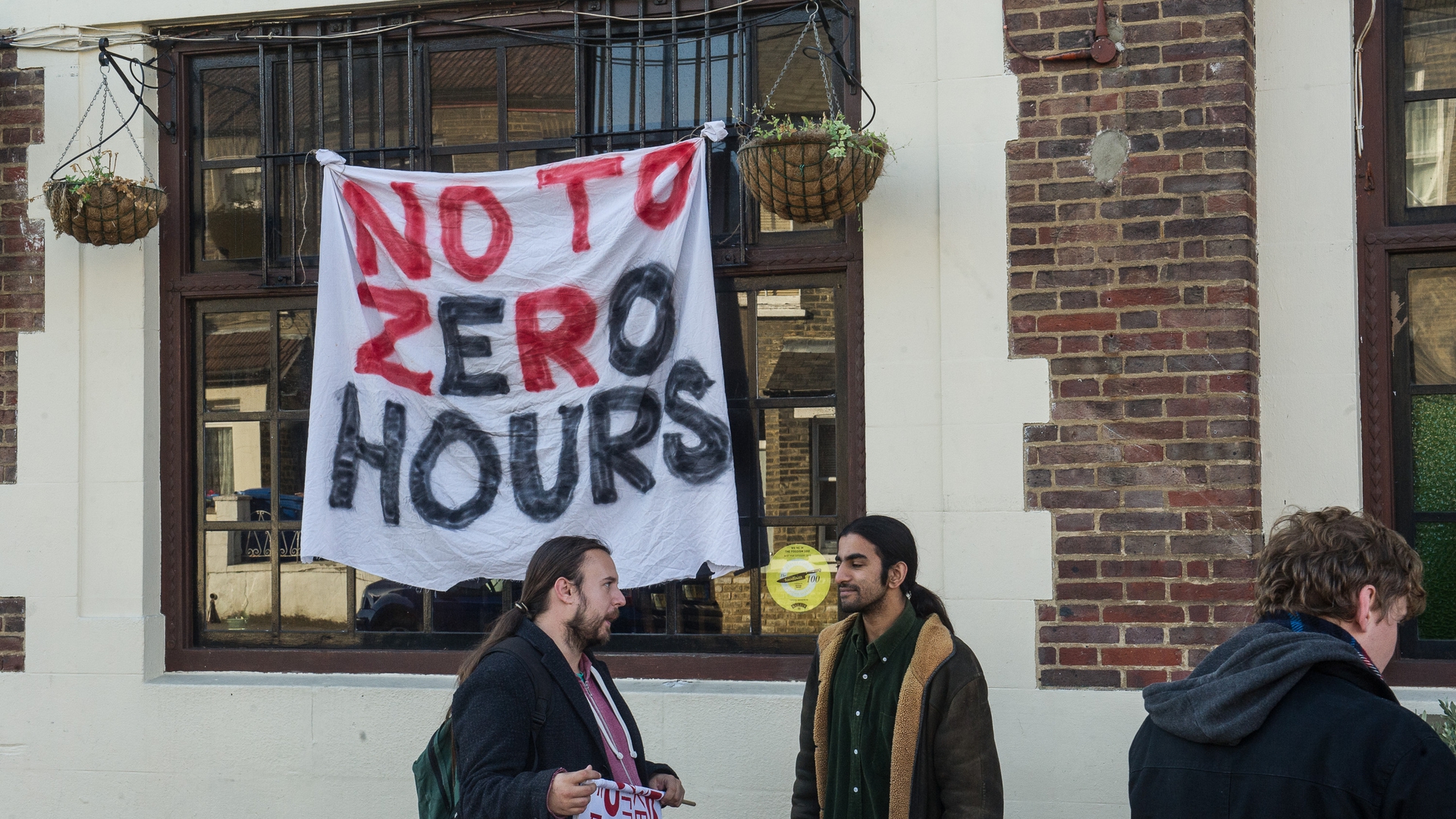

Amardeep Singh Dhillon discusses the formation, successes, and decline of the South London Bartenders Network (SLBN), a network focused on worker-led organising both inside and outside of unions.

inquiry

Post-mortem of a piss-up in a brewery

by

Amardeep Singh Dhillon

/

Aug. 21, 2024

in

Shift Patterns

(#21)

Amardeep Singh Dhillon discusses the formation, successes, and decline of the South London Bartenders Network (SLBN), a network focused on worker-led organising both inside and outside of unions.

I was a full time bartender for four years and a part time bartender for a further two years, finally leaving hospitality work in 2023. Over that period, I worked in three sites, but spent the majority of my time working at the community-owned pub The Ivy House in South East London. I took part in the unionisation drive at The Ivy House in 2017 and the successful wildcat strike in 2018, as well as the negotiations around contract terms and union recognition as Branch Secretary of the union, with BFAWU.

The following is a reflection on a hospitality workers network that I subsequently co-founded with other workers in South London in 2020, which was active for around two years and was an experiment in a different kind of worker-led trade union organising. Here, I’ll be tracing the origin and decline of the network we set up, considering the extent of its successes, the nature of the politics that developed within and through it, the limitations of the network model we developed together, and whether there is still scope for this kind of organising model to aid organising in a sector as transient as hospitality. Most of these reflections - particularly around the nature of pub work and the links between the hyperlocal and the transnational - are the result of years of conversations with members and ex-members of South London Bartenders Network, rather than my own original ideas.

The Sector

With the ever-increasing privatisation of public space - and in a city in which many of us don’t even have living rooms - pubs in particular play an important social role, almost akin to a community centre, providing social space and the chance to construct a hyperlocal community to belong to. Of course, pubs are also spaces of exclusion. Whiteness, patriarchy and queerphobia are still present, and often the violence of their expression is exacerbated by intoxication. As transactional spaces, and with stock and operating costs ever rising, they are increasingly inaccessible to many Londoners struggling with precarity and poverty, with the average pint now setting you back over a fiver. Pubs themselves are also implicated in gentrification, both as valuable plots of land that can be run into the ground for a decade before being sold to developers in “up and coming” areas, and as spaces that mark up prices in response to an uptick in disposable income that accompanies the arrival of wealthier residents, pushing out less wealthy locals in the process. Hospitality workers themselves are often the victims rather than beneficiaries of these exclusions.

Many pubs are ultimately owned by private equity and venture capital firms, and following the money can lead to unexpected places. Greene King, which runs over 2,700 pubs, is owned by one of Hong Kong’s largest property developers, CK Asset Holdings. It also owns and operates the longest natural gas pipeline in Australia, an air conditioning company in Canada and Northumbrian Water Limited, which has spilled thousands of tonnes of raw sewage into the North Sea. Laine Pub Co, which runs over 50 pubs, is owned by Punch Pubs and Co, which is owned by Fortress Investment Group, which is majority owned by Mubadala Capital - the Emirati sovereign wealth fund that invested in the Israeli cyberweapons NSO Group that developed Pegasus spyware used to spy on Palestinian human rights activists. Mubadala Capital recently partnered with Proprium Capital Partners - the owners of Admiral Taverns - to build a property portfolio in Tokyo and Osaka worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

At a local level, however, hospitality workers are excluded from and often unaware of these transnational currents of unimaginable wealth, that are in part animated by their poorly-paid labour. On the face of it, pub work looks simple enough - pour some drinks, wash some glasses, clean the lines, serve some food, clean up at the end of the night. As anyone who has been a bartender knows, however, the real work is expansive: it ranges from cleaning up vomit, glass and excrement, de-escalating violent situations, safeguarding minors and administering first aid, to dealing with the police and emergency services, huge levels of emotional labour towards customers we may grow to hate or love and providing some of them with the only human interaction they get outside of their own work.

Outside of pubs, the work is even more wide-ranging: preparing huge quantities of food in kitchens or bakeries, risking repetitive strain injuries from canning beers or hernias and chemical burns from the intensive manual labour involved in brewery work, braving poorly-paid monotony in a dusty coffee roastery, or facing routine harassment in fast food joints. The hospitality sector is much wider than that great British institution, the local pub, but as the majority of South London Bartenders Network were engaged in, well, bar work, it naturally forms the focus of these reflections on our experiments with union organising in South London.

South Long Bartenders Network

SLBN developed in the context of - and was shaped by - a new wave of political activity that followed the end of Corbynism. The spike in trade union activity in response to the pandemic; the explosion of mutual aid networks and community provision; the BLM uprisings; the Kill the Bill movement and the emergence of a national Copwatch network; the emergence of the Campaign for Psych Abolition and the resurgence of anti-raids groups. Many SLBN members were active in these spheres of organising.

The network model was inspired by community unionism - including the BFAWU fast food workers campaign Peckham Needs a Payrise which focused on building union density in a locality rather than targeting one specific employer - and influenced by the structures of local mutual aid groups. Its formation also emerged off the back of a successful wildcat strike at The Ivy House pub in 2018, and a gradual realisation among some staff that workers organising themselves had the potential to get wins that externally-directed trade union campaigns might not. We chatted to our friends, who also worked in bars, cafes and breweries, and realised that while hospitality work is transient, the workers themselves tended to move between pubs, bars, cafes and breweries within easy travelling distance of where they lived. A few of us began to gauge interest with our friends, and spoke to workers involved in other local union campaigns for advice.

In 2019, when the first serious discussions around the idea of network took place, it wasn’t uncommon to hear other trade unionists write off hospitality as a sector with organising potential. I heard people say it was too precarious, the workforce too transient, and while there had been a few wins - The Ivy House, Brighton Wetherspoons, Unite Hospitality in Scotland - it was generally “too difficult.” A few of us shadowed the brilliant BFAWU organiser running Peckham Needs a Payrise, hitting up workers in Nandos, KFC, Burger King and Wetherspoons, and quickly realised that there was appetite for fighting back in some of the most precarious workplaces when people felt like they were being invited to direct their own struggle.

Some of us had had experience of trade union campaigns - to varying degrees of success - and were critical of the top-down nature of some of the organising we had seen. We were also aware that trade union officials were often ill-placed to support hospitality organising, not understanding the specific dynamics of our workplaces and evidently inexperienced in attempting to support hospitality workers. At the same time, particularly in the wake of the successful wildcat strike at The Ivy House, there was a real feeling that it was possible to organise hospitality workers, a belief that there was power in organising in our localities (rather than just against a specific employer) and a desire to think through what formation might make that possible.

The premise was simple - socials and industry nights with free or cheap booze, regular meetings for hospitality workers (and any allies who wanted to lend capacity) to think through our experiences of work, a Whatsapp chat for co-ordinating everything, and a commitment to supporting other workers who wanted to organise. We were gearing up to launch in early 2020 when Covid-19 hit and the necessity of some kind of formation became undeniable - so we ditched the socials as lockdown was imposed, set up social media accounts and invited anyone who was remotely interested to join a zoom call. I think 6 people attended that first call, some of them total strangers to me. What emerged out of that first meeting was, in retrospect, pretty astonishing.

We focused on our own workplaces initially, and soon we were reporting back about our attempts to get organised on the shop floor to the network in weekly meetings. Pretty organically, workers who had heard of us through word of mouth began to reach out through mutual friends during crisis points in their employment. We represented them - and each other - in disciplinaries, supported their unionisation campaigns and helped them see disputes through ACAS right up until claims were lodged in court. We called this part of the work “casework”.

The bulk of the casework we undertook was with workers who were not union members at the point at which they needed help - and had been turned away by trade unions as a result. We wryly referred to this work as “guerrilla unionism”, as it often involved being economical with the truth - yes, this worker is definitely a member of a trade union; yes, I am definitely an accredited trade union rep; yes, we definitely have access to some of the best lawyers in the country; yes, we have already gone to the press, so if [REDACTED] doesn’t provide legal representation for these workers we’ll have to publicly state that the union is not supporting them.

Our view of our role in relation to trade unions became increasingly unclear as time went on. Some members wondered if we had simply become an unpaid trade union, doing casework unions should have been doing but with almost no resources. Others wondered if maybe SLBN could become the basis for a dedicated Hospitality Union. Some, myself included, continued to view the casework as a means of bringing workers into the union movement where its apathy, inefficacy or bureaucracy would otherwise have alienated them.

The Heights

By the time the first lockdown had finished, SLBN had become a serious commitment for about a dozen workers. We had members in huge chain pubs and independent pubs, franchise pubs and community-owned pubs, breweries and coffee roasteries, cafes and social enterprises. A few months later at its height, SLBN had around 50 members, although perhaps half of these were active.

Over a period of one and a half years, we taught ourselves employment law and successfully represented dozens of workers facing disciplinaries. We developed unionisation campaigns in several sites - some of which were shockingly successful - as well as supported workers in one chain in getting holiday pay reinstated across an entire company. We successfully pressured trade unions to give legal representation to workers whose union membership had not been processed when they entered into dispute, and secured pay-outs for workers who were facing the termination of their employment. We supported migratised workers whose visas were being jeopardised by “creative” accounting and working practices. We organised socials and reading groups, and we tentatively began to develop a politics in relation to the industry we were working in, particularly through researching the links between global finance and the hospitality sector - which we hadn’t seen discussed elsewhere.

These politics began to emerge concretely with an invitation from Notes from Below to collectively undertake a workers inquiry- the conversations involved in writing the piece provided us with a shared analysis of the terrain that we were fighting on, and we began to situate our struggles at work within wider class antagonisms.

One of the largest pieces of casework SLBN undertook related to the firing of two workers from a brewery where staff had been unionising during the pandemic. While the pretext for their firing was that they had taken a few cans of beer without paying for them after a shift, this had long been common practice and these workers had additionally been demanding holiday pay and other rights accrued on the basis of having worked continuously for two years at the company, and therefore being classified as “employees”. Both were people of colour and had been involved in the unionisation drive. They were invited into a hearing and summarily given 24 hours to resign.

When the workers reached out to SLBN, an emergency meeting was held late at night online and a small casework team was convened to quickly establish a timeline of events, solicit legal information, establish what the workers actually wanted as outcomes from fighting their dismissal, map out the varied breaches of employment law the company had potentially committed, and develop a plan of escalating actions. With SLBN’s support - including an SLBN member representing them as a trade union rep - workers were able to force the company to follow an actual disciplinary process, a meticulous record of every instance of communication (which included emails to the board threatening legal action when the general manager refused to engage) was kept, and the case was seen through right up until ACAS mediation, at which point a union lawyer was engaged to take the case on to court. One worker took a pay-out to resign, unable to afford the long fight with the courts being so backed up, while one worker was able to see things through to a tribunal. The case was eventually settled out of court, more than a year after initial contact had been made with SLBN.

The stakes felt high, but every win was exhilarating. By July 2021, bartenders and trade union organisers from other parts of the country were getting in touch, and we were confident enough in our own potential to develop a “How To” guide for workers interested in setting up a bartenders network in their own locality, in response to tentative interest. Around the same time, SLBN members began to do “drop-ins” at hospitality sites where we had no presence to speak to workers, particularly around Southbank, getting upskilled in how to have recruitment and organising conversations in the process.

The success of the network was also evidenced by invitations from several trade unions to formally affiliate, with the promise of full autonomy within them and access to union resources. We debated the benefits of doing so, but the experiences of several members with trade union campaigns in hospitality ultimately led us to reaffirm that part of the utility of the network was that it enabled workers to organise “in and against” their unions where necessary, and for us to work with several unions without getting involved in union politics around encroaching on each other’s territory or “poaching” organised workers. Our orientation towards the workers first and foremost meant that we had no loyalty to any particular union, although we firmly saw them as our allies. In this way, it felt genuinely different to relying on overworked, paid union organisers - as fellow workers we had skin in the game, we understood the realities of the work and far from a service-provision model, we were trying to prove that as workers we were best placed to organise ourselves.

Alongside SLBN, friends of members set up Empower Workers as a sister organisation, responding to the need for legal information to inform our approach to disputes and disciplinaries. Key to enabling us to press on with casework while we were still learning about what constituted detriment, poor practice or a breach of the law, Empower Workers produced guides on employment law and its functioning, took on fundraising and at the point at which SLBN became dormant was working towards a comprehensive guide to employment law targeted at the hospitality sector specifically.

Abolition

Looking back over the minutes and agenda items of SLBN meetings, it’s surprising to be reminded of the scope of our ambition. So often, organising in the workplace can be articulated in terms of conditions and pay alone, but within a year SLBN was seriously discussing our relationship to harm and addiction, our complicity in criminalisation and thinking through what abolitionist approaches to hospitality work could look like. Many of us had experienced violence or harassment at work, and had intervened in violent situations between customers. Linking up with Good Night Out, most of us began pushing seriously for employer-funded de-escalation training within our own workplaces.

One campaign that never got off the ground was developed in response to Project Vigilant - an initiative whereby plainclothes police officers would be placed around hospitality and nightlife sites to surveil and identify predatory men. Ironically, this policy proposal was a response to the public outrage after the murder of Sarah Everard by off-duty police officer Wayne Couzins. We were all too aware of the pervasiveness of misogyny and sexual assault, but didn’t trust the police to keep us (or anyone) safe. We were equally aware that an increase in surveillance and police intervention would be racialised and racialising, and have the effect of making pubs more dangerous spaces for marginalised people. Our proposal was that instead of introducing cops into pubs, the Mayor of London should make de-escalation training for all staff a prerequisite of alcohol licensing.

The beginnings of a reckoning with the wider social implications of making interventions as bartenders are evident in this draft text taken from the minutes of a meeting in May 2021:

Bartending is not seen as skilled labour - and the average hourly pay rate reflects that. But in alcohol- and drug-fuelled environments, we are responsible for breaking up fights and de-escalating confrontations, intervening when someone is being harassed and dealing with people suffering from severe mental health issues and homelessness. Out of the forty or so hospitality workers in our network, not one has cited the police as a central or even a useful resource in the majority of cases.

By actively claiming our positionality as hospitality workers to link our fight for better working conditions to resistance to the further incursion of police into our communities, we began to explore the systems of surveillance and criminalisation that we were often made complicit in. This included discussions over the anecdotal increase in hiring security in pubs that hadn’t done so before the pandemic; questions around the implications of ID checks on the door for undocumented migrants; strategising around how to fulfil the insurance obligations of filing police reports and comply with company policy around harm while refusing to hand over CCTV to police to reduce the potential for criminalisation in non-fatal circumstances; and what responsibility we had as legal drug dealers in encouraging vulnerable people struggling with addiction to have “just one more”.

This appraisal of our role in surveillance and facilitating or countering harm extended to discussions around recognising our intuitively abolitionist responses to those experiencing acute mental health crises or exhibiting non-typical behaviour. None of our members would call the police if we witnessed a customer having a public meltdown, but we were now becoming attentive to the ways in which coercive powers were similarly embedded within social services too, and recognising that our go-to responses (getting them a cup of tea, trying to calm them down or move them to a less over-stimulating space, offering to call someone or keeping tabs until they were ready to leave the venue) were also in line with a developing abolitionist politics.

The Decline

We achieved shocking successes organising with SLBN, but it has been dormant now for as long as it was ever really active. After 1.5 years, it became clear that we had not succeeded in building a formation that could withstand the departure of a few key members. Intense periods of activity around high-stakes casework left members burnt-out, and the promotion of some members to management positions at work compromised their membership of the network. The interest of other workers wasn’t always converted into activity, and despite the consensus-based horizontal organising model, labour and power weren’t evenly distributed. On top of this, some members left the industry and therefore hospitality organising ceased to be a matter of their own material interest.

Most of all, the social element of the network was never fully consolidated. Before the pandemic, this social element had been envisaged as the primary vehicle for developing a base, encouraging identification with the worker subjectivity, delivering training and political education as well as bringing other workers in. The big plans for monthly industry nights that would be free for trade union members, 5-aside football tournaments to bring workers from different sites into contact with each other, and linking up with artists and musicians from South London’s music circuit never came to fruition.

We did the best we could under lockdown conditions, with “pub quiz” nights on zoom, an outdoor reading group geared toward trade unionist political education and “ranting circles”, where we would facilitate chatting shit about our employers. Once lockdown ended, we did meet in person in parks and in pubs - but the relationship between “organising meetings” and “socialising” was never inverted in the way that it needed to be. In other words, we weren’t able to bring workers who weren’t ready to start organising in their workplace into a social space that would encourage the proliferation of a culture of worker-to-worker solidarity in South London. The durability of the SLBN model could have come from consolidating a broader social base, out of which workers who weren’t formally part of the network could have access to the tools to organise themselves. We had always been clear that we didn’t see ourselves as a special vanguard tasked with raising consciousness - we had got pissed off enough to organise when the precarity and disrespect became intolerable in our own workplaces, and we trusted that other workers would do the same if given resources and an open offer of support.

In retrospect, this desire to begin with establishing a social base chimes with the role trade unions historically played in working class communities at the heights of the labour movement in Britain. The failure to reorientate ourselves towards socially embedding the network among a broader base of workers was partly a result of burnout, and partly the nature of hospitality work in the first place. The need to do so had been recognised during a series of strategy discussions at the beginning of 2021, but our intensive engagement in casework at the time and our shift-patterns meant that it was difficult to get the industry nights off the ground.

The Aftermath

Since the network fell dormant, many pubs have become the sites of a different kind of struggle. In 2023, The Honor Oak Pub was targeted for 8 months by the far-right for hosting Drag Queen Story Hour. Month after month, locals co-ordinated an anti-fascist resistance in the face of fascist violence and police repression, and I myself was arrested and convicted for a breach of public order outside the pub in June. While the fascists were decisively seen off at almost every encounter, in the summer the manager was sacked (apparently for unrelated reasons) and the pub “paused” Drag Queen Story Hour - to date, it has not been reinstated.

This was, ultimately, a defeat for anti-fascists that stemmed from a misanalysis of their strategy. The Nazis were successful because we had failed to organise effective counter-power with regards to the pub chain, which we should have anticipated. In the aftermath, I found myself wondering how, over a period of 8 months, we hadn’t actually thought to engage the workers by linking the fascist presence on the streets to their own precarity at work. I’m convinced that, had the workforce in the pub been organised, the event could not have been shelved so easily. With the demonisation of trans people (and by extension drag shows and queer people generally) reaching new heights in the wake of the Cass Review, it’s clear that organising bartenders has to be an important component of anti-fascist work, at least for as long as their workplaces are being smashed up by the likes of Combat18, Blood and Honour and the EDL.

The genocide in Gaza has again reminded me of the necessity of organising in the sector. While Palestine might feel a world away from the pints we pour, the role of real estate speculation and asset management firms in the sector means that some sites at least are implicated in finance capital that could as easily be used to buy up luxury properties in Atlanta as it could be invested in an Israeli bank financing illegal settlements. It feels like a pipe dream to imagine separating hospitality sites from financialised capital - but if it is possible, it will only be possible if the workers themselves are organised against those who convert the profits they generate into investment opportunities abroad. A key ex-SLBN member, Liz, had this to say when asked about the potential of hospitality organising beyond agitating for better pay and working conditions:

“SLBN (as opposed to unions) and the casual yet close knit nature of hospitality workers could produce the perfect ground for developing new methods of protest. Hospitality workers are uniquely placed to be able to deliver short, sharp actions with high public visibility and impact - such as 90 minute shut downs during derby matches in local areas, for example.”

At several points in the last two and a half years, ex-SLBN members have expressed an interest in reviving the network. Most of us, however, no longer work in hospitality, and there is an enduring belief that it was our position as workers that had enabled us to achieve some real gains. In the last few months, however, we have come into contact with workers at several pubs in South London who have expressed an interest in organising.

Our experiment has already had unexpected afterlives - East London Hospitality Network emerged in 2023 and was ambitiously active for several months, though it is now also dormant; musicians in Leeds are quietly applying the network model to organise against corrupt promoters, recognising the parallels between hospitality work and other forms of (literal) gig work; and workers in the South East have recently got in touch expressing interest in learning about what worked (and what didn’t) with SLBN.

Without making any promises, it feels like there is enough energy in South London to at least attempt to bring together current hospitality workers with ex-SLBN members to discuss what can be done to support the organising that is already (quietly) happening. Maybe this could be the revival or reinvention of SLBN, or maybe it will lead to a new model, shaped by those for whom hospitality organising is not now a passion project or an origin story, but an urgent necessity rooted in their own material conditions. If you are such a worker, in South London or elsewhere, and you think you can organise a piss up in a brewery, do get in touch.

Featured in Shift Patterns (#21)

author

Amardeep Singh Dhillon (@amardeepsinghd)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?