Rebellion at the LSE: a cleaning sector inquiry

by

Achille Marotta,

Lydia Hughes (@lydiakathleenh)

February 9, 2018

Featured in No Politics Without Inquiry! (#1)

Notes on an inquiry of the cleaning sector in London and grassroots resistance

inquiry

Rebellion at the LSE: a cleaning sector inquiry

Notes on an inquiry of the cleaning sector in London and grassroots resistance

Introduction

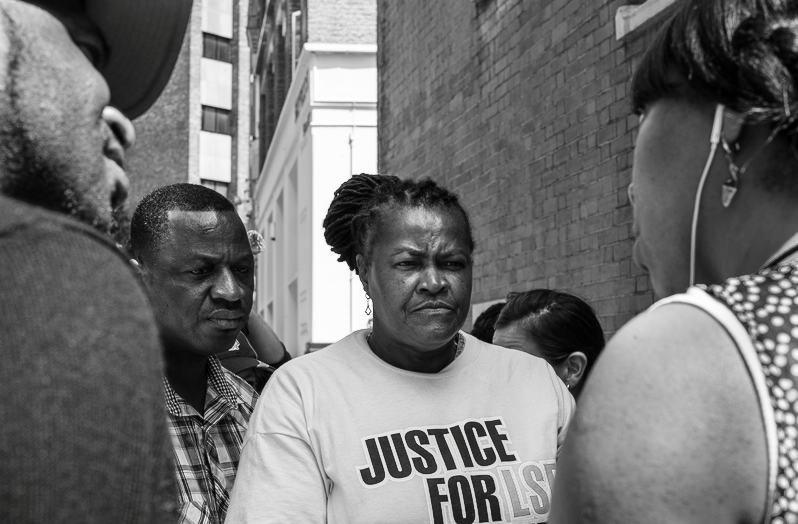

The cleaners’ struggle at the London School of Economics (LSE) had a resounding effect on the radical and trade union left. How could it not? The cleaners seemed to reverse history, beating the tide of precarity and outsourcing ‘at a time of stigmatization of migrant workers and weakening of trade unions’.1 After ten months of campaigning with United Voices of the World (UVW) - including seven strike days, several demonstrations, and two occupations - the cleaners not only achieved their demands of equal terms and conditions with in-house staff, but forced the LSE to employ them directly.

The struggle was spectacular, in every sense of the word. Black, migrant, precarious workers rebelled against exploitation and invisibility in the belly of the neoliberal beast. It was their turn to speak - and they did so outside of Unison and the official trade union recognition agreement. The student-run Justice for Cleaners campaign helped to organise this spectacle, which publicly shamed the university and disrupted its day-to-day functioning. This was the winning tactic. But however many solidarity breakfasts we organised, however long we spent on the picket line, we maintained a feeling of cluelessness. This turned into an awareness that the picket line - the spectacle - was only half of the story.

We decided to inquire into a world which remains unknown and of not much interest to the Left: the world of the cleaner in the workplace. Next to none of the coverage of the strike deemed this world significant.2 We insist this should be our starting point, however routine or banal it might seem to both cleaners and other activists. Because here lies not only the production of clean space, but of rebel workers.

We tried to see the workplace from the viewpoint of militant cleaners. The premises for this article were given to us by B. when she first spoke at an open meeting: “We are in slavery. The only thing they have not done to us is shackle us and whip us. But by words we are whipped, by tools we use we are whipped.” The first two parts of the article deal with these whips and shackles.

The result was these scraps of inquiry, based on long interviews with three militant UVW members. We know that they are not reflective of the entire workforce. However, we hope these notes can be the starting point for a wider process of co-research with London cleaners, who at least since the beginning of this century have formed some of the city’s most tenacious and far-reaching waves of working class insubordination.3 We want to document the entire cycle of these waves, looking beyond their crests and crashes to those deep swells which were generated far from here - in Colombia or Jamaica - gathering energy underwater, only to reemerge with a spray that drenches the highest and mightiest of institutions. The final part of the article is therefore dedicated to resistance, starting from the self-organised refusal to comply, which we believe to be present in any office or university.

Exploitation

Work intensity

The system of outsourced cleaning is based on competition over the client’s contract, in this case the LSE. Outsourcing companies vye over the provision of the cheapest service, while at the same time maintaining their own profit margins. The real ‘competitivity’ of firms therefore hinges on two factors: the immiseration of workers and the squeezing of their labour. The first is the payment of poverty wages,4 the second is compulsion to work harder. Outsourcing companies race to provide the most clean space in the fewest possible hours, for the least amount of money. The enforcement of this low pay and high work rhythm is often achieved by violent ‘extra-economic’ means, which we will deal with later.

At the level of work organisation, the basic methods of increasing the work intensity (the rate of exploitation) are the following: 1) the expansion of space to be cleaned by the same number of workers; 2) the reduction of the number of workers tasked to clean the same space; and 3) the reduction of time in which workers must clean the space.

One worker we spoke to began working in the library for the outsourcing company ISS in June 2009, along with three others. Within three months, the library workforce was reduced from four to two. This 100% increase in work intensity eventually forced him to take several months off due to physical and mental exhaustion: “I could not sip even water for the 8 hour shift I was doing”.

When the LSE did not renew the contract with ISS and went into ‘partnership’ with Resource Group, the library staff was increased again and this exhaustion was diminished. But work was intensified in other ways. Whereas before specialised deep cleaning - such as unblocking toilets - was done by external, trained ISS staff, now the LSE and Resource expected cleaners to do it. In other parts of the campus, work intensity as a whole was increased through all the methods mentioned above. Within a few months, cleaners organised in the IWW cleaners’ branch - a precursor to UVW - staged a protest with the following demands:5

- Stop the LSE from reducing the cleaner’s working hours

- Stop the LSE from intensifying the cleaner’s working day

- Stop the LSE from giving with one hand and taking with the other

- Stop the LSE from treating the cleaners like second-class employees

- Publicly expose Resource’s management’s inveterate practice of racist bullying

The characteristics of this protest - including a disruptive samba band and chanting, as well as direct confrontations with management - had many similarities with the struggle that would shake the campus five years later. While a few of its participants would also play a role in the 2017 strike, only Latin American cleaners joined the IWW, and not the Caribbean and African migrants who would come to head the UVW strike. While the 2017 campaign focused primarily on achieving equal terms and conditions with in-house staff, one of its demands was also a review of workers’ workload and the disciplinary procedures used to enforce it.

Throughout the past years, cleaners also witnessed a growing work intensity through the university’s increase in student numbers: more people, more dirt, more work. Added to this was the use of university space for catered commercial and academic events as well as ‘customer service’ facilities. This, combined with the ceaseless redevelopment projects, expanded the space to be cleaned.6 All of these are examples of the ‘neoliberalisation’ of the university, a process that could potentially create common demands between cleaners, students, and teaching staff.7

Health effects

The greater work intensity is well-known to consume the bodies of cleaners with a whole host of physical ailments. Until the recent victory, these issues were worsened by the deadly Statutory Sick Pay of only £89.35 a week, which is received only after the third day of illness. The campaign particularly emphasised the case of M., who was hospitalised after injuring her knee in the library whilst working. After taking four days off, she was forced to come back to work to support her family, causing her knee to swell. And as if this was not enough, during a five minute rest to cope with the pain, M. was photographed by a manager and given a disciplinary.

These kinds of health problems caused directly by the work and the paltry sick pay can be found across the city’s whole cleaning workforce. The low wages and high costs of living in London - rent above all - mean that workers simply cannot afford to take days off sick. Permanently disabling and even fatal cases have been made known to us, and when it comes to mental health issues, the conditions are equally appalling. One could write a whole study of how such progressive institutions as the LSE expend the bodies and minds of the working class in London.

Division and discipline

Compared to say, a factory assembly line, cleaning work can allow for a degree of mobility around the workplace which escapes the levels of monitoring sought by management. This is particularly the case on a larger and more scattered structures like the LSE. The most militant cleaners used this to their advantage to organise the strike: discussing in person or through WhatsApp, convincing colleagues, and distributing union membership forms were all possible during work hours.

But this relative independence varied widely according to the shift and building, even on the same campus. In other cases, it became clear to us that these techniques of exploitation did not just consume workers in the direct sense, but divided them politically, decomposing them as a workforce. Cleaners that are isolated, overworked, and dispersed around the campus are good for management. This busy loneliness prevents the everyday correspondence which forms the basis of workers’ power. Inversely, defeating work intensity gives workers more freedom to organise during working hours.

As conspiratorial as it might sound from the outside, this is a tendency that workers recognise. From the cleaner’s viewpoint, each form of work organisation appears not as a neutral fact but a political technique of discipline and division. Take, for example, the system according to which the day shift begins only an hour after the morning shift ends: a cleaner who works the former described this to us as “another propaganda of not letting the people come together and know how to get to talk and discuss things”. It took the strike for workers to finally meet each other, after years of cleaning the same building. Despite our attempts through solidarity breakfasts, we were equally unable to engage many cleaners who worked this 6am-8am morning shift, in part because they literally ran to other jobs.

To this we should also add the use of overtime and cover shifts. Because contract hours are relatively low, workers often depend on the assignment of extra hours, which are granted at the discretion of the bosses. This can create competition between workers, forcing them to stay in favour with management. In practice, this system has same effect as zero hour contracts by creating dependency, leaving workers vulnerable to abuse and fearful of speaking out.

A similar example is the use of touchscreen tablets, on which cleaners have to check off tasks as they complete them. One cleaner suggested that its function was for discipline, and that they could always use the microphone or camera to spy on workers. Yet - to the chagrin of our interest in “computerised Taylorism” - everyone dismissed the relevance of these tablets. No one knew how they worked or who looked at the data. Nothing seemed to have ever come out of this supposedly disciplinary technique. Management didn’t even train cleaners to use them properly, and cleaners made all sorts of technological blunders, intentional or not. We can only guess, but perhaps the tablets are simply a way to extort more money out of the School, fooling them that the provided service is more rationalised than it really is. At least for now, they have not replaced the necessity of radios as a tool for organisation and supervision.

Oppression

So far we have limited ourselves to the realm of economic competition: competition in the squeezing of human labour. Already this legal system of outsourced work organisation elicits the harshest criticism from the workers: “it is an embarrassment for LSE to keep having slave masters in the 21st century”. These are the fundamental whips and shackles. But the system is also a breeding ground for ‘extra-economic’ means of coercion which are themselves instrumental to exploitation. Bullying, racism, sexism and homophobia fester in the system, reproducing themselves by their own logic.

Racism, clientelism and documents

All UK universities exhibit a clear racial division of labour. While tenured professors are overwhelmingly white, further down the wage scale the workforce becomes more likely to be migrant and of colour. This is particularly clear with the in-house/outsourced divide, which LSE cleaners continually described as nothing less than segregation, a two tier workforce. This can be seen in the video, shot by the UVW secretary, in which black cleaners described being unable to use the very cafeteria they clean: view it here.

National and ethnic divisions are also felt within the cleaning workforce itself. Lower-level managers - who in recent years have all been Nigerian - tend to hire workers from their own ‘community’ and favour them over others in the assignment of hours. These workers tended to be absent from the UVW picket lines. Workers we talked to explained this through the relationship of patronage/clientelism the Nigerians had with their managers, a relation which begins outside of the workplace, through family and other community relations. There is a story that goes around the workforce about the recruitment process: “at the sessions at church, [the manager] would stand up in the end and say ‘anybody who wants a job, come to LSE’. And she’s most probably vetting them first to see if they’re legit, and if they aren’t, yes come in.”

The clientelism is particularly strong for these ‘not legit’ workers, those with irregular documents. It was repeatedly claimed that managers were taking money from workers as a guarantee that they would maintain their hours and job. We were told about cases of workers who worked long hours and still struggled for money, while those who refused to pay were summarily laid off.

Outsourcing companies may formally be against corrupt managers taking money from undocumented workers for their personal gain, but as long as it divides and disciplines the cleaners, it benefits the multinational. The blackmail of being reported keeps workers docile, while favouritism keeps them dependent on the boss, dividing the workforce along lines of ethnicity, language, and kinship.

We therefore have to reject the idea that this is a problem of the backwardness of African migrants in an otherwise rational and meritocratic European institution. It is the poverty of London life which forces people into these relations of dependency. Without all this, outsourcing companies’ profits would be significantly lower. Ultimately it is Noonan who gains the most from this system, and the LSE did everything possible to protect it.

Homophobia and sexual harassment

The same argument has to be made with regards to other forms of abuse. It is convenient for the company to explain sexism or homophobia in terms of the national culture of migrant workers. When Daniel - a leader of the strike and himself a Kenyan migrant - was suffering heavy homophobic abuse at the hands of his coworkers, Noonan’s account manager just told him: “it’s in their culture”.

This disregard of abuse is financially motivated: if a grievance was upheld, the company could be found liable for thousands of pounds. Thus, while the company was comfortable with sacking three cleaners who left work an hour early,8 Daniel’s abusers were left untouched. The low sick pay and annual leave meant that Daniel was unable to take time off to recover from the mental health issues inflicted from this abuse. Instead, he was offered to move to another Noonan site.

But Daniel decided to stay and struggle. The collective victory at the LSE laid down the conditions for his battle: thanks to the newly won sick pay, Daniel was able to take time off to recover. He took Noonan to court with the demand to have the bullies sacked. His tribunal ended on the 18th of January 2018 and we will know the verdict in a month - after the publication of this piece.

Management’s tolerance of abuse, together with the conditions of the contract, also put women in a particularly vulnerable position. Cleaners explained to us that sexual harassment was routine and embedded into the shift system. Workers’ dependence on managers’ assignment of hours left them particularly vulnerable to these individuals. Abusers would assign women to particular buildings and assault them at times when they knew they would be alone. One of the many reasons why women were on the frontline in denouncing the entire structure.

Rebellion

In such a system, it should be no surprise that struggle existed prior to UVW. Even alongside all the divisions, workers resisted management on a daily level: standing up to management’s bullying, refusing to carry out extra tasks, working slower so as to not be assigned more work. These everyday forms of resistance may be short-lived, confined to few workers, but they exist as a result of direct experiences in the workplace, and tempered those fighters who would come to lead the strike.

At the same time, more powerful struggles circulate throughout the working class. One kind of these is the union struggle in London. When three LSE workers were fired for leaving work an hour early, one of them contacted an organisation they had heard good things about. After a few months, UVW had the ‘LSE 3’ reinstated. This success story spread like wildfire through the workforce. UVW was known to be a fighting union and LSE cleaners joined in their dozens.

Another kind of struggle is the kind which circulates internationally, brought across the world by migrant workers. The movement of London cleaners, now spanning two decades and several union organisations, would probably not have been possible without the experiences migrants had in their home countries. As an example, we briefly discuss the life experiences of struggle of B., one of the leaders of the LSE cleaners’ strike.

The making of a militant

B was born in Jamaica, where her family’s land was bought out by an American Bauxite mining corporation. Looking for work, she migrated to the Dutch territory of St. Martin in the Antilles, where she joined UFA, a militant union led by Willy Haize. Haize became a workers’ leader in the 1969 Curaçao revolt, which began when outsourced workers at Shell Oil demanded equal wages with in-house staff.9 In 2007, B. organised workers into UFA in a building supplies store she worked at. When management tried to frame her by suspending her for using a cell phone, she organised an immediate wildcat strike with all of her 14 colleagues. They did not walk back in until they had secured the right for workers to communicate by phone during work hours.

B. on the picket line with Willy Haize10

In 2008, she began working for ISS at LSE, and immediately began struggling against the bosses. She spoke up and refused to comply, and paid for this by not receiving cover shifts. Everybody knew her face, and regardless of their nationality they would seek her out for advice:

“Sometimes I would just encourage them. Or I would just tell them you need to write this, you need to do this. Or sometimes I even wrote to the managers myself. And I said “Listen, what is happening in this university is unlawful.’ I even go on the website, I check with ACAS. I go to the Citizens Advice Bureau to get legal answers. And I come back and I say look at this. This is it.”

After two years away from the LSE, B. began working for Resource in 2012. She joined Unite with a group of other cleaners, including Daniel, but failed to get anything off the ground. Unfortunately they were unaware of their Latin American colleagues organising in the IWW at the same time.

In 2013, independent of any union, B. won 12 days extra holiday pay for cleaners working weekend shifts, after discovering they were only receiving leave for weekday work. She explained: “This is it. You can’t take away my rights. Honestly. When it comes to my right I will die for that.” In 2016 - after her friend and two other laid off cleaners (the “LSE 3”) were reinstated thanks to UVW - she met Petros Elia (the General Secretary of UVW) and they drank in the Shakespeare’s Head (a pub near LSE) to celebrate their victory:

“I went over there was I said Petros let me tell you something. I can’t applaud you much more. Wonderful job. I said as of today I, [B.], am going to join your union. […] And I am going to organise. Watch. Yous is going to become the main one in here, to represent us […] you will see, I am going to recruit.”

Indeed, the recruitment was not led by the union, but by B. and others like her. The victory of the LSE 3 provided a powerful example to convince people to join. From then on, UVW provided a space to bring together a group of militant cleaners, holding regular meetings to organise for industrial action.

Workers and unions

When B., Daniel and others went to Unite in 2012, they were told that they needed 20% of the workforce to join the union for them to take any action. Such procedures lagged behind the more militant workers, and fail to engage those who have doubts. B. simply said ‘I wasn’t impressed.’

Meanwhile, the LSE Unison branch was loathed by the most militant cleaners. It was dismissed as being part of management, and cursed in the same breath as Noonan and the LSE. Many had never heard of Unison before the dispute, while those who had were not wooed by them.

As the struggle proceeded, Unison assumed the role of mediator between LSE/Noonan and the cleaners, of which they represented only a handful. They established a ‘formal three-way partnership working arrangement’11 to negotiate the ending of a dispute they had no control over. The rage of the cleaners was never channelled through Unison, only towards them. The cleaners refused to accept Unison’s role and actively rebelled against it, interrupting branch meetings and holding signs on the picket lines denouncing them.

What explains the failure of the recognised unions on campus? We can first of all note that they began from above. Their starting point was the negotiation table, for which workers’ activity was only a pawn. At the end of the day, they believed that workers did not have power, that they could not win. This was revealed by the fact Unison members were spreading information among workers that they could lose their jobs if they joined the picket line, effectively placing them on the same side as management.

Meanwhile, UVW began from below: from the perspective that workers can immediately struggle for their rights and win through direct action. It unconditionally supported and encouraged the initiative of cleaners, even if they were in a minority. The strategy of moving straight to direct action tactics such as strikes, protests, and occupations gave strength and confidence to workers, bringing them into direct confrontation with their bosses rather than mediating between the two. Negotiations only dealt with the question of when, not whether, their demands would be met. This confidence in struggle until victory could be seen from the most militant cleaners, who did not fixate their slogans and speeches on the particularities of terms and conditions but on the more radical demand of ‘equality’.

In fact, improved terms and conditions were only a part of what mobilised cleaners. Central to UVW’s discourse and culture is the reclaiming of dignity and respect which - in a workplace and sector where bullying and discrimination are endemic - struck a chord with the daily experience of cleaners. To this we can add UVW’s main slogan - “No longer invisible!” - which resonated with the alienation that cleaners experience from the product of their labour: not just clean space, but the people who use it. Despite the fact that teaching, studying, and researching would not be possible without hours and hours of cleaning work (a fact that cleaners are fully aware of), cleaners are treated as ghosts. This alienation was compounded by the racial division of labour. Thus UVW meetings, protests, and pickets became not only sites of organisation and struggle, but places where workers could, for once, make themselves visible and make their voices heard.

Moving forward

This struggle for a voice, dignity, and respect is more revolutionary than any demand for better pay or terms and conditions. A wage rise can be negotiated and conceded, but real dignity and respect would require a complete revolution in how the university - and ultimately society - is structured.

The demands and actions of the cleaners contained the seed of workers’ power. It is the recognition of this striving for power which gives UVW and other militant union organisations such an appeal to outsourced migrant workers across the city. Our task today is to take workers’ will to power and make it permanent. We need to create direct coordinations of workers which can concentrate and spread this offensive struggle to other workplaces and sectors of the workforce.

To this end, we have been working on a monthly bulletin called Precarious Notes for outsourced and precarious workers. We hope it can be used as a medium to circulate struggles across the class, and reflect on tactics and organisation.

But we also hope that research can be returned to working class organisation as a guide to action. We see these scraps of inquiry as the beginning of a larger project to understand the political economy of the cleaning sector, the changes it has undergone since the early days of outsourcing and the various kinds of struggles cleaners have waged, ever since the Cleaners Action Group in the 1970s.12 To this end we have compiled a questionnaire for the cleaning sector (found below), focused initially on universities, adapted from those of our comrades in the Angry Workers collective .13 We provide it below as an initial framework for anyone who wishes to take up this proposal for inquiry into cleaning work, and urge you to get in touch with us to plan this out.

Email us at [email protected] for a more extensive guide on workers’ inquiry in the university.

Photos by Gordon Roland Peden. For more visit his blog .

-

Acciari, Louisa and Davide Però, 2017. On the Frontline: Confronting precariousness, outsourcing and exploitation - lessons from the LSE cleaners. ↩

-

As a partial exception, we can cite Virginia Moreno Molina’s three-part series on The Prisma (see especially Cleaners in struggle: Where are their rights? and Cleaners: the 21st century slaves? ) for their longer interviews with several striking cleaners. In addition to these articles, we recommend our friend Joe Hayns’s chronicles of the picket lines in Novara Media and Jacobin Magazine . ↩

-

A history of this wave of struggle from the perspective present article will have to be saved for the future. For an introduction, we recommend Richard B’s excellent Crisis in the Cleaning Sector (2013). ↩

-

In the ‘wage’ we also include that portion beyond the hourly rate, i.e.: sick pay, holiday pay, pension and maternity/paternity/adoption leave. The LSE struggle broke out over these ‘terms and conditions’ - which were all at the legal minimum - in spite of the university’s London Living Wage policy. ↩

-

IWW, 2012. URGENT PROTEST!!! Justice for the #IWW #Cleaners at #LSE! Weds 13, 1PM. See also Peter Marshall, 2012. LSE Cleaners Protest . ↩

-

One militant worker who cleans the library cited to us the recent transformation of the majority of the Ground floor into the “LSE LIFE” centre, a “pioneering facility dedicated to students’ academic, personal and professional development” which has had over 200,000 visitors in its first 9 months, and therefore takes significantly more work to clean than the bookshelves which previously took up the space but for which no more time is allotted for cleaning. http://www.lse.ac.uk/News/Latest-news-from-LSE/2017/06-June-2017/TEF ↩

-

As public funding has been cut, UK universities have sought to rebalance their budgets by increasing the proportion of international students forced to pay exorbitant fees (now 70% of the LSE student population) and investing into infrastructure which can be capitalised, or capitalising existing infrastructure (consider the use of halls as hotels over the holidays). The cuts are particularly significant for the LSE, due to the low level of funds available to the social sciences and the university’s student satisfaction rate, one of the lowest in the country. Last summer, it received the lowest classification of “bronze” in the government’s Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). If its classification does not go up, the LSE will not be able to charge undergraduates more than £9,000 a year. It is in this context that we have to see its recent decision to opt out of the TEF . A bad reputation risks jeopardising its most valuable asset: international and postgraduate students who attend the School for the marketability of its degrees in the business and financial world. In other words, the LSE risks a crisis which they may seek to offset through the diminution of the pay and conditions of its staff, a process from which the status of ‘direct employee’ does not provide protection, as precarious teaching staff know all too well. The key point is that this process can provide the basis for the mobilisation of other university workers and students, if these groups can learn to replicate the effective political behaviours of cleaners. The upcoming UCU strikes, for example, could make much use of loud, militant picket lines which bring in different groups and truly disrupt the day-to-day functioning of the university. ↩

-

UVW, 2016. Breaking News: “LSE 3” Reinstated ↩

-

Mark Kilian, 2012. Curaçao 1969: eiland in opstand . See also Joseph H. Lake Jr., 2004. Friendly Anger: The rise of the labour movement in St. Martin. ↩

-

The Daily Herald. Wednesday, May 23 2007. Front page. ↩

-

Young, Andrew. 2016. Dispute between LSE cleaning staff and external contractor Noonan. ↩

-

See May Hobbs, 1973. Born to Struggle; and Sheila Rowbotham, 2006. Cleaners’ Organizing in Britain from the 1970s: A Personal Account. ↩

-

Angry Workers, Questionnaire for workplace reports II ↩

Featured in No Politics Without Inquiry! (#1)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

No Politics Without Inquiry! (1995)

by

Ed Emery

/

Jan. 29, 2018