There and Back Again, a Yoghurt’s Holiday

by

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1),

George Briley (@GeoSBriles),

Matthew

September 21, 2023

Featured in Seeds of Struggle: Food in a Time of Crisis (#18)

On workers’ power across the food distribution industry

inquiry

There and Back Again, a Yoghurt’s Holiday

by

Callum Cant,

George Briley,

Matthew

/

Sept. 21, 2023

in

Seeds of Struggle: Food in a Time of Crisis

(#18)

On workers’ power across the food distribution industry

Introduction

Human society has always had to organise itself around the production of food. Whenever a group of people have lived together, they have established a way of making sure they have enough to eat. When they have failed to do so, that society has collapsed. Our own way of producing food in Britain today has emerged out of a centuries-long process of capitalist subsumption that started with the enclosures of common land following the Black Death.

Today, food is an almost universal commodity. We pay capitalists, and in return they give us access to the most fundamental of goods required to keep us alive. If you can’t afford to pay, then you can’t afford to eat. Whereas food production was once the work of millions of peasant subsistence farmers, it is now a profitable capitalist industry.

The business of food production and distribution is incredibly concentrated. Three companies - Tesco, Sainsburys, and Asda - account for over 50% of total grocery retail sales in Britain.1 Within these large supermarket chains, a small number of suppliers provide the majority of goods. The Angry Workers collective have argued that major retailers also have an increasing role in food production, with their power as massive buyers allowing them to shape production in agriculture and food processing - sometimes even by directly investing in machinery and reorganising the labour process.2 We also import almost half of our food from other countries, with 12.5% of all food consumed in Britain arriving through the just 61 ferry crossings every day from Calais to Dover.3

To decrease expenditure and increase profits, the supermarkets all import their fruit and vegetables from the same part of the world at the same time. Once the season ends in that part of the world, they then import from another. This enables them to always stock our favourite fruit and vegetables, no matter the season. However, this leaves their supply chains at great risk from the climate crisis. Extreme weather in Spain and Morocco earlier this year led to crop failures. Because 51% of tomatoes consumed in Britain are grown in these two countries, we had half empty shelves.4 This concentration also leaves food supply chains at disproportionate vulnerability from human interruptions too - such as strikes, slowdowns and labour shortages.

The ‘just in time’ economy requires manufacturers to coordinate with suppliers and clients for prompt restocking, rather than building up large stockpiles of goods. This system changes the traditional buyer-seller relationship, where goods are produced first and then sold to consumers.5 This ‘lean space management’ means food storage mostly happens during transit, making the system vulnerable to disruption. As a result, the roads and ports can be more critical points of disruption than the warehouse itself.

If we want to understand the capitalist food system that prevails in Britain, then we need to understand these supply chains. In this article, we are going to explore the logistics of food imports through a simple object: a 500ml pot of yoghurt. We start our analysis after the cows have been reared, the grass has been grown, and the milk has been collected, transported, and cultured. All of those processes involve intensive applications of labour, and are worthy of inquiry in their own right, but they lie beyond our focus here. Instead, we are going to explore the features of the class composition of the process of road and ferry transport that move food imports from the point of production into the supermarket distribution systems. We’re doing so on the basis of some worker interviews, but primarily through an extensive reading of the internal publications of the capitalist class: from market research and white papers to consultancy reports. Our analysis isn’t final. Instead, we want to lay the groundwork for deeper inquiries that understand the realities of work in this chain at a more granular level and from the workers’ point of view.

Our first moment of analysis takes place in the loading bay of a yoghurt processing facility in an industrial area on the outskirts of Paris, as a pallet of yoghurt (packed into pots, subdivided into cardboard bulk packs, and wrapped in protective covering) is loaded into the back of an articulated lorry.

Yoghurt on a Lorry

The man driving the lorry is called Cristian. He’s 36, and from Romania. He’s about average height with a big barrel chest and thinning hair. When we talk, we are standing in the HGV section of a service station on the M2 in Kent, one of the major routes out of the port of Dover, and he’s taking one of his legally-mandated fifteen minute breaks. For six weeks at a time, Cristian leaves behind his family and travels to Western Europe to work, before taking a 3-week break back home. During these working stints, he drives 36 hours a week on the same route, back and forth from the outskirts of Paris to a supermarket distribution centre in the Greater Manchester area. On top of that driving time, he also does four to six hours a day of other work, such as vehicle maintenance, supervising loading and unloading, and administration. In total he usually works 12 to 14 hour days, with a legally-mandated 45 hour rest period once a week. He doesn’t only drive yoghurt - sometimes it’s chocolate, sometimes it’s gardening goods. “I couldn’t list them all,” he says. He works in this pattern because the wages he makes going back and forth across the channel dwarf anything available at home. “In Romania the average pay is around 500 Euro a month, but working here I earn around 3000 Euros a month.”

His metric for prices is a can of Monster energy drink. It costs the same in Dover as it does in Bucharest - but here, the wages are six times higher. But the wages have a downside. “It’s not a very good job because I have to spend so much time here when I would rather be in Romania. I stay a long time here each shift and I miss my family.” Asked if he intends to keep working this way, he answers “I hope not but I think I might have to. I don’t know what else I would do.”

Cristian works for a small firm. His boss owns 14 trucks, and their movements across the continent are coordinated by a team of three planners. The planners send him GPS files containing his pick up and delivery points and he works out his own route between them. He drives for seven or eight hours a day. At the moment, he’s not managed too intensively: “My boss tries to be nice to me as there are not many drivers around, so he needs me.”

He’s not a member of a trade union. “In Romania we have two or three of these types of unions, but I don’t need one. I’ve worked seven years for the same boss and I’ve never had any problems.” On this trip across the Channel, he has a 28 year old trainee driver, also from Romania, in the cab with him. He’s showing him the ropes. He says that back home there are a lot of people training to become drivers because they want higher wages. Sometimes he teaches in the training academy. “Lots of people are learning to drive trucks.” And with that, his fifteen minutes are over. He hops up the step into his cab and starts the engine, ready to head north.

Cristian’s experience is not unusual. It is broadly representative of the 274,000 people who work in the £33bn road freight industry. Overall, the food import supply chain is characterised by six key features, explained below.

A low concentration of capital in road freight

Industry estimates suggest that operating a 44-tonne truck for 3 months costs about £25,000 before licensing costs.6 That’s a lot of money, but it’s a drop in the ocean compared to the amount of investment required to set up a supermarket. This low cost of entry means that capital is fragmented in the road freight industry, with only one company (DHL) boasting more than 5% market share. Firms like Christian’s are common, but the majority of registered businesses in the industry are even smaller, with 84% of enterprises employing fewer than five staff members in 2021. New firms are setting up and going bust all the time, and drivers who can cobble together the cash often leave existing firms to go independent as self-employed owner-operators. As a result, the road freight workforce is subdivided into lots of tiny fragments split across thousands of firms, with many of the more experienced drivers ending up ascending into the petit bourgeoise, even if only temporarily.

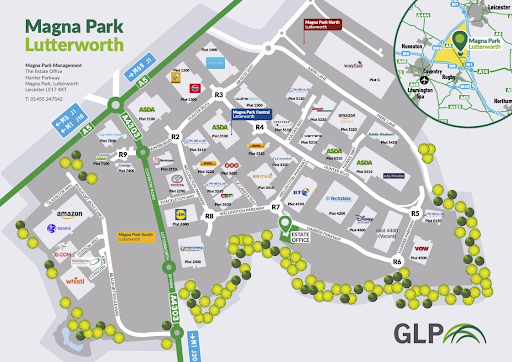

These tens of thousands of businesses are disproportionately clustered in the midlands, specifically in the 289 square mile ‘golden triangle’ between the M4, M1 and M6. From there, trucks can reach 90% of the UK population in 4 hours. Between 2011 and 2021, the number of business premises dedicated to transport and storage increased by 88%, with the sub-category of freight transport by road premises increasing specifically by 114% over the same period. These premises have disproportionately been concentrated in clusters like Rugby, Daventry, and Milton Keynes. Magna Park in Lutterworth is home to 29 warehouses in the single biggest concentration of distribution centres anywhere in Europe. Asda operates 5 of them, and Lidl another one. That’s a lot of yoghurt.

Supermarket power

The network of tens of thousands of micro-enterprises becomes concentrated around the big beasts of the corporate world, the ‘lead firms.’ 33% of road freight services are bought by retailers and wholesalers. In the case of food imports, these lead firms are the big supermarkets. They have huge power over the road freight industry and the hundreds or even thousands of small firms and individual owner-operators they interact with - either directly or through 3rd party firms. Contracts between supermarkets, producers, and logistics firms can specify Service Level Agreements (things like delivery times and trailer temperatures) that have to be maintained during transportation. Lead firms ensure that they have visibility over their supply chains by using software platforms that integrate roadside data such as GPS locations with key documentation, thereby allowing for the operation of a just-in-time system based on live point of sale data from supermarket tills and sophisticated forecasting. Walmart set the example of how to integrate data flows in supply chains to give the lead firm visibility and control through their pioneering use of barcodes - and now that principle has been applied to almost every commodity chain.

Volatile profits

Demand in the road freight industry closely follows demand in the economy more generally. This is less true in the case of food, where a certain constant baseline of demand is always guaranteed, but the level of demand in the rest of the industry will have knock-on effects in how many firms are competing for the same food import contracts and at what prices. Capital in the sector is also highly exposed to fluctuations in fuel prices. Prices for freight transport are often renegotiated on a quarterly short cycle to reflect this variability of costs. As a result, profits are volatile - losses can be large and unpredictable, and firms often lack the financial backing required to absorb them.

A labour shortage

The COVID-19 pandemic combined with Brexit massively reduced the number of drivers available in the UK road freight industry: HGV licence tests were suspended, creating a blockage in the driver training pipeline; migrant workers began to return home in large numbers; and after the end of the transition period UK employers have been left with permanently reduced access to the EU labour market. In 2021 the Road Haulage Association estimated that there was a shortage of more than 100,000 qualified drivers. This led to an increase in workers’ individual bargaining power and resulted in wage increases, with wages rising from 23% of industry revenue in 2020 to 26% in 2021, where they have stabilised since. This has contributed to squeezing average profits from 12% to 9% over the same period. The government and capital have responded to try and reduce the shortage, with temporary visa schemes and increased training funds being used to try and get around the bottleneck.

Regulated work intensity

The example of the garment industry shows how low concentration industries with volatile profits and high relative labour costs tend towards extreme strategies for labour exploitation. However, road freight has unique legal barriers to forcing workers to work faster for longer. The first of these is the system of speed limits. HGVs are limited to 60 mph on the motorway and 30mph in built-up areas. Working faster than this is illegal. Working hours are also regulated by leftover EU law. The exact specifics of the regulation are complex, with a number of possible patterns of break times and working hours allowed, but basically it mandates workers take a 45 minute break every 4.5 hours, and drive a maximum of 9 hours a day, 56 hours a week, and 90 hours a fortnight. Compliance with this legislation is monitored by a tachograph. Falsification of tachograph records is possible; in 2016 440 HGVs crossing into the UK were found to have “interrupters” fitted that manipulated the data collected by the devices,7 but it’s unclear how widespread this practice continues to be.

Potential technological change

There are two key workforces in the road freight industry, drivers and planners, and they both face varying forms of technological change. Planners face change through the increasing automation of delivery planning and supervision of the kind that might be more familiar from delivery platforms like UberEats. Software like Roadnet Anywhere promises to “dramatically reduce miles driven, fuel costs, and driver overtime to realise greater profitability” by generating routes, managing documentation, and collecting and analysing driver data. Planners seem highly exposed to a degree of technological unemployment in the near future, as the introduction of algorithmic management to the industry eliminates tasks and likely lowers the overall skill level of the job.

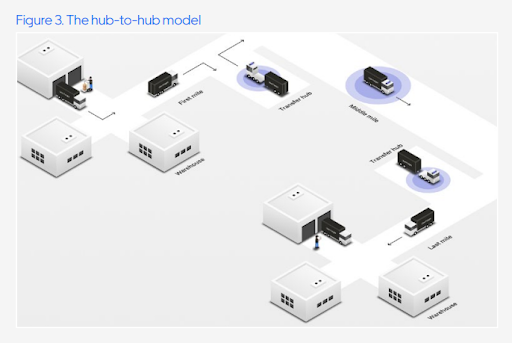

Drivers face technological recomposition via a greater variety of routes.The potential development in the industry with the most journalistic coverage devoted to it is the introduction of autonomous commercial vehicles. Zenzic, the UK’s joint government-industry venture that aims to accelerate driverless technology and direct 200 million of investment spending, expects commercial deployment pilots to emerge in road freight over the next three years, and for those pilots to have resulted in projects ready for large scale investment from 2027 onwards. The most likely next jump forwards will take place when vehicles are capable of operating fully autonomously within a limited range of conditions - e.g. motorways. Uber Freight, a subsidiary freight technology business under the Uber umbrella, envisages a ‘hub-to-hub’ automation model where autonomous vehicles do the long hauls along motorways before human drivers based out of transfer hubs take over for the more complex last mile.

But there are also blunter approaches to raising productivity: a fifteen-year pilot scheme, started in 2012, fitted 2,800 trucks with LSTs (Longer Semi Trailers) which are capable of carrying two more rows of pallets or three more rows of goods cages.If the pilot proves successful, per-driver productivity will rise by roughly 7-10%. In-cab surveillance technology, like Amazon’s Driverai developed by Netradyne, utilises computer vision AI systems to monitor driver-facing cameras. This technology, when combined with driver performance tools from companies like Microlise, enables increased managerial control and monitoring. It tracks metrics such as acceleration, braking, and more, intensifying oversight over drivers.

None of these developments are guaranteed to result in success. A five year trial into truck ‘platooning’ (whereby three trucks driver very close together in formation to reduce air resistance and thereby fuel costs) recently ended in failure following a failure to deal with other drivers’ lane merging behaviours. Autonomous vehicle development has already been severely delayed, despite an estimated $100 billion of investment since 2010, and there is no sign of technical consensus about the best way to achieve level 4 autonomy. However, a wider range of firms have a significant interest in technically recomposing road freight. Relatively big players like DHL would stand to benefit from the introduction of capital-intensive level 4 automation as they could leverage their turnover to achieve cost savings ahead of other market participants. Lead firms might also use their vast size and existing experience of running distribution centre-to-shop delivery fleets to vertically integrate food imports and achieve cost savings. Both moves would increase the cost of market entry and concentrate capital - potentially recomposing the workforce in the industry and creating a more direct and shared antagonism between drivers and managers. State pressure to reduce emissions and lower the ecological impact of road freight might also dovetail with this trend: only the biggest firms have the cash available to achieve, for example, rapid electrification.

Yoghurt on a Ferry

Cristian, and the tonnes of yoghurt in the back of his HGV cannot simply drive all the way from Paris to Manchester, because of the 31 miles of water in the way. Given the island nature of Britain, it is unsurprising that 95% of all imports and exports into and out of the country are transported by sea.8 To get our yoghurt to Manchester then, Cristian will have to queue up at Calais to board one of the 61 ferries a day to Dover, using one of three operators running freight ferries across the channel - P&O, Irish Ferries, and DFDS. Dover is the largest roll-on/roll-off port (that is, a port where cargo is driven off rather than being lifted off by cranes) in Britain, with 1.7 million HGVs, and 12.5% of all our food passing through the port every year.9 The crossing itself takes around 90 minutes, and each ferry carries up to 180 HGVs. New models of ferries are however increasingly introduced to expand capacity - just a few years ago the same ferry services were only able to hold 90 HGVs per journey.

Concentrated Capital

Unlike with HGVs, the concentration levels of capital here on the freight ferry are high. Purchasing one ferry, let alone enough to run a regular service, is extremely expensive, as are docking fees and (turbulent) fuel costs. Whilst average profit margins are just about healthy at 7% of total revenue, they are not particularly high. With capital buy-in high, and profit margins relatively low, only a few operators are able to function. This means a great deal of freight goods are concentrated onto a small number of boats, run by an even smaller number of companies. For example, P&O, the largest ferry operator in the UK, only operates four ferries out of Dover, and when including all companies, only 12 freight ferries in total operate between Dover and Calais. Ferry services then constitute an incredibly vulnerable part of the supply chain from factory to supermarket - a strike or blockade at the ports on either end of the channel could block up a huge number of goods, and force through rerouting to other already busy ports further away. Subsequently, the workers who make these ferries function hold a similarly incredible amount of power. The ferry system in Dover therefore seemingly exemplifies Deborah Cowen’s argument, that logistical supply-chains are characterised by their vulnerability.10

Ferry Workers’ Power

The history of seafaring is one of a generally militant workforce.11 The word ‘strike’ even originates from sailors’ protests in the 1760s, in which they ‘struck’ their sails, preventing their ships from functioning.12 So why do we not see ferry workers regularly exercising this power they have over the supply chain?

The numbers of workers operating the port in Dover are fairly small, numbering at just over 8,000. P&O’s Ferries near 24/7 services in Dover are staffed by just 500 crew members. Although each ship has a relatively large crew because of the need for rapid loading and unloading at each side of the channel, this is still an extremely concentrated workforce. This concentration must be one of the factors behind the RMT’s ambitions to have 100% union density in the sector.

However, ferry strikes are few and far between. In recent years the only strikes we have seen have been on the French side as part of national days of action against Macron’s pension reforms, and a number of days by border force agents in the Port of Dover itself, organised by the civil servants’ union PCS. In fact, ferry workers’ seem firmly on the back foot after P&O’s illegal sacking of 800 ferry workers nationally last year, which saw them replace permanent staff with agency workers who are paid less than minimum wage and work far longer hours.13 The response to these sackings were militant: workers occupied their boats, and when evicted by private bailiffs wearing balaclavas and carrying handcuffs, they blocked the roads to the Port. Yet this action has seemingly fizzled away on the ground, and beyond parliamentary lobbying and media campaigns, organising around the issue by official unions seems to have petered out. Similar trends, in terms of dodging labour legislation and hiring workers on low wages with long hours, also plagues Irish Ferries14, another of the three freight ferry companies at Dover.

We have many questions to ask then, and answers to uncover, if we wish to encourage this working-class power to be exercised in the ferry industry. What role does the managed decline of coastal towns, in both Britain and internationally, play in pacifying the naval workforce? What role does the ‘split’ between permanent and casualised workers play in this pacification? How can the growing precarity of the ferry industry be turned into a class weapon? How can we link labour and social movements to these isolated, floating workplaces? Answering these questions will demand much more work on the ground.

Why the fuck do we care about yoghurt?

By the point we receive it, our yoghurt has seen many different labour processes. Each stage of the commodity chain presents various opportunities for the working class to take action, even if they haven’t been fully realised yet. However, our understanding of how workers can effectively utilise these opportunities is limited due to our lack of direct connections with their perspective. While we can identify potential leverage points by observing the commodity chain from above, to really understand it we need to see it from the workers’ point of view. Therefore, our next task is to strengthen our connections with workers in these industries and conduct further inquiry to gain deeper insights.

But the view from above does explain something about the trade union strategies in the road freight industry. Beyond some isolated wage victories at small firms, Unite’s current big picture strategy is a class collaborationist appeal for sectoral collective bargaining. Rather than trying to organise shop by shop in a massive industry with lots of tiny employers, the union is attempting to appeal to the state and capital’s interests in reducing labour turnover to establish a national collective bargaining deal covering every worker in the sector. This collaborationist appeal for partnership unionism in the sector based on a common cross-class interest in driver retention paints a picture where the interests of all parties can advance in harmony15. But that isn’t the reality on the ground, where technological developments and increases in labour supply look set to initiate a renewed cycle of struggle between workers and bosses.

It’s also vital to recognise that the apparent leverage of drivers in a lean production system is heavily limited in other ways. When workers in one firm strike, other small players can swoop in and provide their services instead. Capital in the sector is highly geographically mobile by design - any one small group of drivers will struggle to be more than a speed bump in the path of the logistical juggernaut. On top of that, trucking work culture often has strong reactionary elements. It seems obvious that a blend of petit bourgeois owner-operator self-interest and the masculinity of a 99% male workforce both shape many of the historic example of driver militancy, from the US trucker go slows of the 1970s to the Brazil truck strikes of 2018,16 and the Canadian “freedom convoy” during the pandemic.17

But there seem to be class struggle strategies that could win real economic and political gains using the leverage of the industry. Sectoral collective bargaining could be fought for using go-slows on essential infrastructure like the M25; drivers could refuse en masse to disembark from ferries at Dover; and so on. Similarly, ferry workers could use their concentration to threaten to choke off a significant chunk of the UK’s food imports for a range of ends, from immediate pay and conditions improvements to wider working class political goals.

The road freight industry is changing rapidly, with state-led initiatives to loosen the labour market through education and migration18 potentially combining in complex ways with technological changes in the near future. This could lead to a rapid concentration of capital in the sector, redrawing the battle lines between labour and capital in new and potentially more explosive ways. The ferry industry is also changing, with an employer’s offensive seemingly focusing on lengthening the working day and increasing its reliance on a more precarious migrant labour force. However, struggles over this recomposition are ongoing, and it could possibly open up new terrains of struggle, both through the process itself and its potential results.

Who controls the organisation of work in this scenario has implications beyond industrial disputes over wages and conditions. The work of logistics is also important to consumers; if we want that yoghurt, it matters how it got to the shop we buy it from. For consumers, there’s many different dynamics that make food logistics important. We don’t want to pay too much for our yoghurt. We might (hopefully) not want workers’ delivering that yoghurt to be severely exploited because of what passport they hold. We should also be concerned about the environmental impact of our yoghurt reaching us. Whilst regulation is one way in which these concerns might be mediated, reform via Westminster politics seems unlikely to say the least. The alignment between the interests of consumers and workers makes for a potential political composition able to wield significant leverage. The emergence of that solidarity currently looks unlikely, but is that potential, and the leverage it could allow us, a gamble we can really afford to ignore?

-

Mintel, UK Supermarkets Market Report 2022. ↩

-

AngryWorkers, Class Power on Zero Hours. London: PM Press UK, 2020. ↩

-

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (22 December 2021) United Kingdom Food Security Report 2021: Theme 2: UK Food Supply Sources. ↩

-

BBC News (3 March 2023) Tomato shortage: How far is Brexit to blame?. ↩

-

Bernes, Jasper (2013) ‘Logistics, Counterlogistics and the Communist Prospect’, Endnotes 3. ↩

-

Commercial Motor (2 May 2023) ‘The true cost of becoming an owner-operator’, Commercial Motor. ↩

-

Cave, Rob. (24 September 2017) ‘Rise in Lorry Tachograph Tampering on UK Roads’. BBC News. ↩

-

Fraser, Mia (2022) Sea & Coastal Freight Water Transport in the UK, IBISWorld. ↩

-

Department for Transport (16 March 2023) Road goods vehicles travelling to Europe: 2022. ↩

-

Cowen, Deborah (2014) The deadly life of logistics: Mapping violence in global trade . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ↩

-

Linebaugh, Peter and Rediker, Marcus (2001) The Many Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon Press. ↩

-

Clover, Joshua. Riot Strike Riot. London: Verso, 2016. ↩

-

Topham, Gwyn (17 March 2023) ‘One year on, has P&O Ferries got away with illegally sacking all its crew?’, The Guardian. ↩

-

Blackburn, Daniel (9 Sept 2021) ‘Collective bargaining machinery: a solution to ‘chaos’ in the HGV sector’, Unite the Union. ↩

-

Winslow, Cal (23 Jan 2021) ‘The 1970s: Decade of the Rank and File’, Jacobin. ↩

-

Leedham, Emily (5 Feb 2022) ‘Canada’s “Freedom Convoy” Is a Front for a Right-Wing, Anti-Worker Agenda’, Jacobin. ↩

-

Department of Transport (15 June 2022) Future of Freight Plan. ↩

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Coming Indigestion

by

Notes from Below

/

Sept. 21, 2023