Try again: on GCSE resits in further education

inquiry

Try again: on GCSE resits in further education

by

Tom White

/

Sept. 9, 2024

Funding shortfalls, recruitment crises and pay freezes: where next for struggles in further education?

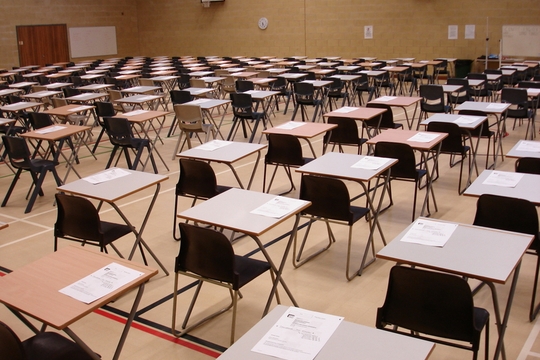

The new academic year begins in England’s further education colleges this week. Among the arriving students will be many who did not achieve a level 4 (equivalent to a C grade) in GCSE English and/or maths during their last year at secondary school. Since 2014 these students have been required to resit these qualifications alongside any new course they have enrolled for at college. This requirement is known by the slightly ominous-sounding acronym “CoF”: condition of funding.

The results for this cohort make for grim reading. For the 2023-24 academic year, the pass rate for GCSE English at further education colleges was 17.9 percent. For maths it was 15 percent. The ongoing detrimental effects of the pandemic are clear to see: in 2019 the pass rates were 27.3 percent and 19.1 percent respectively. Yet even the pre- Covid figures suggest that tens of thousands of students in further education colleges are being subject to a peculiar and cruel form of academic punishment. Many students in the large majority who did not achieve a level 4 in the last round of exams will have been resitting their resit.

The roots of this problem can, to a certain extent, be traced to the schools these students have recently left. Stop School Cuts estimate that 70 percent of schools in England have less real-terms funding now than they did before austerity began fourteen years ago. The teacher recruitment and retainment crisis is deepening. Stress and burnout are common; turnover is high. There are also Michael Gove’s 2010 reforms of GCSE curricula and assessment, which reprioritised high-pressure final exams over coursework. “Anything that allows pupils to do well or work differently is seen as suspicious,” Naomi Grant wrote in 2017, in relation to teaching GCSE English, “as though education must always be skewed so that only a very few can succeed”. Gove’s changes have, though, been embraced by many of the large academy chains that now dominate secondary education. A regressively utilitarian approach to education often goes hand-in-hand with authoritarian behavioural policies.

Many students will arrive at a further education college hoping for a fresh start, only to find that they must retake the same course(s) they recently failed. Those who got a grade 3 (equivalent to a D) have to retake their GCSE. Those who left with a grade 2 or below can, in theory, either take a functional skills level 2 course–a lower level of qualification–or resit their GCSE. In practice, most colleges prioritise GCSE provision. Inevitably, given the narrowness of the qualifications and what is at stake, teaching often leans heavily towards exam preparation and “finding” the extra marks a student needs to nudge them over the level 4 grade boundary.

Those students who need a more personalised, low-pressure route towards improving their maths and English skills are often left adrift once again. Even with the best efforts of teachers, teaching assistants, and support staff, many students are soon faced with the demoralising prospect of resitting an exam they (and we) know they will not pass. There is an obvious alternative to this colossal waste of time and effort. A modular system of post-16 English and maths learning could enable students to build skills and confidence in areas that are useful to them. Students and teachers alike would be freed from the strictures of standardised exams to focus on project work and collaborative learning that could, in its best forms, inculcate a genuine sense of interest in and enjoyment of maths and English. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour pledged to scrap the GCSE resit policy, as part of an ambitious plan to transform education along such lines. Keir Starmer’s government has declined to match this commitment, but has promised a review.

Meanwhile, under existing plans inherited from the Tories, colleges will be mandated to provide students with at least three hours of teaching time per week for GCSE English resits and four for maths, beginning in the 2025-26 academic year. Some colleges are already meeting this requirement. Others aren’t and will therefore need more maths and English teachers. But these teachers will be very difficult to find—impossible in some areas of the country. The sector is already facing a broad recruitment crisis. There is a large disparity in pay between schools and further education and, in vocational areas, between further education and employment in a trade. The new Labour government recently decided not to extend its recent 5.5 percent pay uplift for school teachers to their colleagues in further education, widening this gap still further.

UCU’s “New Deal for Further Education” includes demands for a 10%/£3000 pay rise for all workers and parity with schoolteacher pay within 3 years and a minimum starting salary of £30,000 for teachers. At the further education sector conference in April, it was decided that there would not be an aggregated ballot in June and potential nation- wide industrial action in September, as had been proposed. There have been several local pay disputes that have seen effective organising efforts, but the decision was an acknowledgement that branch density and activity are generally lacking. After years of underfunding and neglect of further education, and of the poorer communities it predominantly serves, many of my colleagues were impatient for a new Labour government. There is already a growing sense of disappointment. Turning this disappointment into anger and rank-and-file activity is now the task at hand for organisers in the sector.

author

Tom White

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The T Levels Mess

by

Tom White

/

Sept. 26, 2023