Introduction to the Legal Workers’ Inquiry

by

Jamie Woodcock (@jamie_woodcock),

Tanzil Chowdhury

May 12, 2025

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

An introduction

inquiry

Introduction to the Legal Workers’ Inquiry

An introduction

In a letter written in 1905 to Elena Stasova and his other comrades, Lenin said that ‘lawyers should be kept well in hand and made to toe the line, for there is no telling what dirty tricks this intellectualist scum will be up to.’1 Lenin was asked what tactics his imprisoned compatriots should pursue at their trial. Either to reject its legitimacy entirely - arguably a precursor to the ‘rupture defence’ made popular by Jacques Vergès - or to use it as a ‘means of agitation.’ Continuing his disdain of lawyers, he suggested to his comrades that their advocates should stick to ‘criticising and “laying traps” for witnesses and the public prosecutor on the facts of the case, and to nailing trumped-up charges.’ Should they stray and criticise socialism, one should, Lenin wrote, reject the ‘scoundrel’s’ defence. It is reasonable to infer that while Lenin thought they might, at times, have an instrumental value, he saw lawyers firmly as agents of the ruling classes.

However, are lawyers not workers, too? And if indeed they have such an esteemed position as functionaries of capital, might that also mean that their withdrawal of labour would give them significant leverage in disrupting it? The ideology of the lawyerly class does not always defer to power. ‘Critical lawyers’, of a disposition and temperament entirely different to the scoundrels that Lenin imagines, ‘seek a theory and practice that makes the overcoming of such oppression a central political task.’2 While some are understandably sceptical of ‘critical’, ‘radical’ or ‘socialist’ lawyers,3 ‘movement lawyering’ and the ‘law centre movement’ position their legal work in subservience to broader political struggles. And while literary and popular culture representations of lawyers may suggest they are financially well endowed, a recent independent review of criminal legal aid lawyers confirmed that many earn around £12,000 in their first few years of practice.4 While many things have changed since Lenin’s time, the question of what position lawyers - or those who work in the legal sector - remain complicated. It is this question that this collection sets its sights on.

This collection of essays, curated by Notes from Below and the Centre for Law and Society in a Global Context at Queen Mary University of London, is a workers’ inquiry into the legal sector in Britain. To our knowledge, there has never been an inquiry like this before.

Workers’ Inquiry is a method that combines research and organising. It is inspired by Marx’s call for a survey in 1880, which asked factory workers questions about their conditions. Later attempts at workers’ inquiry have demonstrated how the act of asking questions about conditions at work can be a politicising process. While the results of an inquiry are important, the process of collectively undertaking an inquiry can form a first step towards organising. After all, organising first involves understanding what is being organised for - or against.

In this collection, we understand ‘legal workers’ broadly. As LSWU (Legal Sector Workers United) write, ‘we aren’t just barristers and solicitors. We are cleaners, secretaries, paralegals, caseworkers, intermediaries, clerks, support staff and legal executives.’ Therefore, we have tried to bring together as many different types of workers in the legal sector, not just solicitors and barristers, but also facilities managers, caseworkers and paralegals, working in a range of different settings, including law firms, charities, chambers, as well as university legal clinics and law centres. We are interested not only in the work that legal orders do in the reproduction of capitalist social relations,5 but also in the ‘useful knowledge about work, exploitation, class relations, and capitalism from the perspective of workers themselves.’6 Following significant internal disputes with its parent union (UVW), LSWU appears to have been rendered mostly inactive as a branch (although individuals remain attached to the parent union in name). These disputes concerned a range of long-standing and unanticipated issues including maintaining adequate strike solidarity funds for strikers (as was noted by strikers at ASIRT7). Many of these members have elected to instead actively organise within Unite the Union’s Financial and Legal Sector branch.8 Some professional associations have also taken action in recent years (for example, the strikes by the Criminal Bar Association9), and others in the criminal legal aid sector have begun to proactively recruit for Unite, including most notably, the London Criminal Courts Solicitors’ Association and the Criminal Law Solicitors Association,10 to build structures to collectively organise for improvements in pay/conditions across the legal sector (with a focus on Legal Aid).

As the Italian workerist Vittorio Rieser states, workers’ inquiries can be conducted from ‘above’ or ‘below.’11 The former involves gaining access to someone’s workplace using conventional research methods to gather knowledge about work, exploitation, social relations and capitalism. The latter is an endeavour of co-production where workers themselves lead the production of knowledge about the workplace. There have been several academic ethnographies of legal practice, ranging from exploring a US corporate law firm,12 law centres,13 to family law practice in the UK.14 Perhaps the most notable study of the legal profession was carried out in the 1980s by the Research Committee on Sociology of Law of the International Sociological Association. It collated reports from over 20 countries and their respective legal professions. In an accompanying essay for the report,15 Richard Abel examined the legal profession, positioning it within the context of a market economy and reflecting on entry into the legal labour market:

My starting point is the uncontroversial observation that all occupations in capitalist economies must seek to control the markets for their goods and services. Professions can be distinguished from occupations in part by the ways in which they pursue this goal and their relative success in attaining it. Changes in the nature of market control illuminate many facets of the recent history of legal professions. Those changes also influence the composition of the profession, the structures within which lawyers practice, their work, income, and status, and the organization and activities of professional associations.16

Abel’s essay then speaks to how labour supply changes have affected legal work’s social and political composition.17 In his 1985 ethnography titled The Legal Profession in England and Wales,18 he explored how the entry into the legal labour market had impacted the racial, gendered and class composition of both the Bar and solicitors and the stratification of labour in solicitors firms,19 similar investigations into work have been made, from examining labour market flexibility, changing work patterns, and ‘the decomposition of professional labour’ through artificial intelligence. Significant though these contributions are, they capture what we might typically understand as an ‘inquiry from above’ rather than that developed from the experience of the workplace. This is where this collection of essays comes in.

Key concepts

The concept of class composition informs workers’ inquiry, both as a framework for guiding the inquiry, as well as analysing the results. For Notes from Below, class composition is defined as:

A material relation with three parts: the first is the organisation of labour-power into a working class (technical composition); the second is the organisation of the working class into a class society (social composition); the third is the self-organisation of the working class into a force for class struggle (political composition).20

The inquiries discussed here aim to understand different parts of this overall class composition. For some, they have focused on the technical composition of the legal sector, inquiring into the labour process and management of workers in different contexts. Other inquiries have examined the social composition of legal workers or focused on how workers are composed politically. Each of these provides an understanding of class struggle in the legal sector, both where workers are actively organising and where capital is trying to recompose the legal sector.

The implications of this go beyond the class composition of the legal sector itself. For example, social composition has been defined as:

A way to understand how consumption and reproduction form part of the material basis of political class composition. It involves factors like: where workers live and in what kind of housing, the gendered division of labour, patterns of migration, racism, community infrastructure, and so on.21

The legal sector often plays a role in the social composition of other workers. Legal workers may intervene in the provision of housing or other resources, or may mediate between workers and the state in a range of different ways. The importance of understanding class composition is therefore twofold in this collection: what is the class composition of the workers in the legal sector, as well as the role of the legal sector in class composition of other forms of work, the economy, and other parts of society.

Attempts to organise legal workers

A common thread running through attempts to explain the lack of organisation among legal workers is a prevailing conceptualisation that the legal profession is hyper-atomised, characterised by a distinct employee-employer relationship which incentivises careerism, and is typically conservative. Michael Mansfield KC, a prominent human rights lawyer and President of the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers, described efforts to organise lawyers back in the 1970s as ultimately unsuccessful.22 The first attempt to unionise solicitors firms was in 1976, with the establishment of ACTSS, a section of the Transport and General Workers Union.23 There were also several (now defunct) unions which historically admitted legal workers, including The Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs and The Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff; but these were not considered appropriate to cater to the distinct work environments of legal workers. The efforts to unionise solicitors firms continued into the 1980s but failed to gain any serious traction and density in membership.24

Legal workers therefore, have either tended to join some of the more prominent general unions (for example, workers at Thompsons, a leading trade union law firm, are typically members of the GMB) or address work grievances through professional associations, such as The Law Society or The Criminal Bar Association, who operate as a kind of lobbying group on behalf of its members. The many professional law societies have meant there has been a significant division of the legal workforce. As Sommerland writes:

Front-line regulators and representative bodies (e.g. The Law Society and Bar Council) are complemented by the Inns of Court (an archaic residue of the Bar’s history, offering barristers and students educational activities and dining facilities) and a range of special interest associations grounded in demographics (e.g., the African Women Lawyers’ Association and the Society of Asian Lawyers), practice areas (e.g., The City of London Law Society and the Association of Personal Injury Lawyers (APIL)) and geographic locations (e.g., Birmingham Law Society). These several dozen groups represent and further the fragmentation of the profession, including its knowledge base.25

This British experience stands in stark contrast to legal workers in places like France where the Organization Syndicale des Avocats, founded by the communist and anti-Zionist lawyer Eddy Kenig, now the Syndicat des Avocats de France (SAF), has been and continues to organise lawyers. While SAF organises lawyers to ensure better working conditions, much of their work also involves political education and participating in efforts to improve the justice system.

In 2019, the Legal Sector Workers United (LSWU), a branch of the United Voices of the World (UVW), was set up in an attempt to fill this union vacuum in Britain. They began their organising by conducting a survey of all legal sector workers to get a sense of the kinds of issues affecting legal workers. The new union sought to initially focus on insourcing legal workers - typically cleaners, part of a broader ambition of UVW - as well as focusing on the pay of its trainees and paralegals.26 In a piece for the Socialist Lawyer, LSWU members wrote that ‘gender pay gaps, racialised divisions of labour, inequality of wealth and income, and high levels of economic exploitation are the norm’, and wanted to position the union to ‘speak with one voice when negotiating with the government.’27 During COVID-19, they saw a three-fold increase in the size of their membership, with much of their work voicing support and organising in solidarity with detained and undocumented migrants.28

Alongside this, organising among lawyers continued within the professional associations. In the summer of 2022, there was perhaps the most significant mobilisation of lawyers taken in recents years. Members of the Criminal Bar Association voted almost unanimously to take industrial action over rates of pay and the pay structure, eventually securing a settlement with the British government.

Law, legal practice, and capitalism

One way in which to explore the contradictions of law and legal work is to make sense of its relation to the prevailing conditions of society. The role of law and legal orders in reproducing the exploitative social relations that are foundational to capitalism have been especially well explored by Marx and Marxists, producing a range of different formulations29 of the relationship between law and capital. As Marx famously wrote in his Preface to a contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, legal relations are not the products of the human mind but are rooted in the material conditions of life. For example, Marx argues:

A philosopher produces ideas, a poet poems, a clergyman sermons, a professor compendia and so on. A criminal produces crimes. If we take a closer look at the connection between this latter branch of production and society as a whole, we shall rid ourselves of many prejudices. The criminal produces not only crimes but also criminal law, and with this also the professor who gives lectures on criminal law and in addition to this the inevitable compendium in which this same professor throws his lectures onto the general market as “commodities”. This brings with it augmentation of national wealth … The criminal moreover produces the whole of the police and of criminal justice, constables, judges, hangmen, juries, etc. ; and all these different lines of business, which form just as many categories of the social division of labour, develop different capacities of the human mind, create new needs and new ways of satisfying them …

The criminal breaks the monotony and everyday security of bourgeois life. In this way he keeps it from stagnation, and gives rise to that uneasy tension and agility without which even the spur of competition would get blunted. Thus he gives a stimulus to the productive forces. While crime takes a part of the redundant population off the labour market and thus reduces competition among the labourers — up to a certain point preventing wages from falling below the minimum — the struggle against crime absorbs another part of this population. Thus the criminal comes in as one of those natural “counterweights” which bring about a correct balance and open up a whole perspective of “useful” occupations …

Crime, through its ever new methods of attack on property, constantly calls into being new methods of defence, and so is as productive as strikes for the invention of machines. And if one leaves the sphere of private crime: would the world market ever have come into being but for national crime? Indeed, would even the nations have arisen? And has not the Tree of Sin been at the same time the Tree of Knowledge ever since the time of Adam?30

Marx describes the development of various productive forces in reaction to the criminal in a similar way to Tronti’s arguments about workers’ struggles as the driving force of capitalism, pushing capital to innovate in response.[^321]

Marxist analysis has offered a range of jurisprudential theories conceptualising the relationship between law and capital; from arguing legal orders are a mere reflection of the economic base (the so-called base-superstructure metaphor); law as an apparatus in the hands of the owners of the means of production (this draws on the famous idiom from the Communist Manifesto that ‘the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie’32); that law is constitutive of the economic base33 through fields such as contract, property law etc; that law is relatively autonomous but determined in the last instance by the economy34; or that law is ideological in that it obfuscates but naturalises materially unequal relationships through formal juridical subjectivity.35

Perhaps one of the most thoroughgoing attempts to develop a general theory of law through Marxism, was that articulated by one of the most eminent legal thinkers of the Soviet Union, Evgeny Pashukanis. His commodity form theory of law argued that law was a historically specific form of social regulation, unique to the capitalist mode of production.36 The juridical subject (an abstracted subject removed from its context) mirrored the commodity form because ‘in order for commodities to be exchanged, their ‘guardians must … recognize each other as owners of private property’; this ‘juridical relation, whose form is the contract … mirrors the economic relation’.37 In effect, the legal form abstracts out the material differences between parties to commodity exchange: the dispossessed worker and the owner of the means of production. Irrespective of the content of laws then, legal disputes simply reproduced this commodity form. As for the state and public law, according to Pashukanis, they derive from this legal social relation, but not as the will of private capitalists. Competition among units of capital make it impossible for them to secure the general conditions of production. Instead, the capitalist state form emerges as an ‘impersonal public power’. The conclusion of Pashukanis’ argument is that ‘proletarian-’ or ‘socialist legality’ is an oxymoron, instead detailing the logical withering away of law in a classless society.

But what about lawyers and legal practice’s role in the reproduction of capitalist social relations? While this book has adopted a more expansive definition of legal workers, we will briefly discuss whether lawyers (solicitors, barristers, paralegals, legal executives, and so on) are classed as workers in a conventional sense. Returning to Richard Abel’s work is useful for attempting to understand the position of lawyers, as professionals, within the relations of production. They appear to sit uneasily in the classical Marxist class distinctions, neither owning the means of production but also distinct from most workers ‘in the work they do and the rewards they receive.’38 However, others have understood that the growing concentration of capital would mean an intermediary class of functionaries would emerge, acting as the agents of capital.39 Bankowski and Mungham capture then how lawyers cannot be in service of the made-poor or working class:

First, lawyers, in the long term, can have no material interest in conceding very much to the poor. In other words, the more the client knows, the less the lawyer is able to earn. And second, a significant erosion of the monopoly of legal knowledge is not in the lawyer’s interest either, for if this base begins to wither away then so does the claim of the lawyer to power and privileges in society. From this point of view it can be seen that the lawyer has need of the poor, but what we have yet to establish is whether the poor need lawyers.40

Following a similar trajectory, Pashukanis wrote that ‘a dispute, a conflict of interest, elicits the form of law, the legal superstructure’.41 If social and political antagonisms are mediated through the legal form, or are ‘juridified’, this means that these conflicts ‘must be mediated by legal experts.’42 Lawyers become the agents of a capitalist form of mediation that needs their specialist expertise, but also alienates social antagonism from popular mobilisation.

Other ways in which to position lawyers are that they are not involved in production but in the reproduction (for example, family law, inheritance, and so on) of capital. Alternatively, lawyers have been understood to have ‘global functions’ such as ‘social control’ (for example, criminal law), structuring relations of production (labour law) and exchange among capitalists (company law).43 A potential riposte may be that there are lawyers that advance, or at least protect, the interest of the working class through immigration, housing, and social welfare law. However, returning to Paskuanis, it can be argued that while the content of those laws may be useful, they are still reproducing the form of social regulation unique to capitalism. Indeed, much depends on our vision of the future: law and lawyers will not set us free. Abel’s analysis also continues to explore processes of proletarianization among lawyers as a result in the changes of their work conditions, particularly as they lose control over the organisation of their work.44

In this collection’s more expansive definition of legal worker, there are those who clearly fit into the category of worker. As the contributions will illustrate, the determination of whether lawyers as professionals are workers, assume an all to easy flattening that can hide more than it reveals.

The call and the contributions

The call for contributions for this collection of essays was launched in November 2023, inviting submissions from as many different types of legal workers drawn from as many different types of legal environments as possible. The call was spread among several networks, including firms and chambers, unions, professional associations, legal charities, and law centres. Most of our authors wrote these essays themselves, either sole or co-authored. Some are based on interviews conducted by the editors, or interviews between the co-authors of the pieces themselves. Though the brief was to produce a workers’ inquiry into their workplace, the range of responses, but also styles in prose and presentation, is compelling. We met with all the writers to explain the brief of the project, the theory informing it, and worked through several edits with all of the authors. Several pieces have been anonymised for fear of reprisals from bosses and, perhaps not surprisingly, almost all of the legal workers who responded to our call primarily work in non-commercial areas of law.

In the first contribution to this book, Roger Bravo* provides a forensic account of the technical composition characteristic of many law firms, foregrounding the ‘deeply entrenched hierarchical structures’ of the workplace. In describing the different types of work present in a typical legal workplace, he identifies how much of the lawyers’ productive labour is possible only through the invisibilised labour of non-legal staff. Bravo also brings into focus how the disciplining effects of competition and the incentive structure diminish the possibility of workplace organising. Taking a long durée approach, he also briefly examines how this culture is nurtured in law school (a point developed by one of our other writers), in which social capital and networks foster a hyper-individual careerism that is anathema to any worker solidarity.

With the growth of clinical legal education in the UK, many British law school’s now offer legal advice and representation. In this original and insightful contribution, Robert Jones* and Gordon Dalziel,* who both work in a legal clinic for a university, provide an important historical context to the emergence of university legal clinics before outlining the technical composition and stratification of labour of their workplace. They describe ‘the shit jobs’ which are apportioned to the most junior student volunteer staff, so that others can continue the work that they are not otherwise qualified to do. As they both astutely observe, legal clinics provide an important pool of free student labour. Echoing elements of Roger Bravo’s analysis, Jones and Dalziel also discuss the social composition of their workplace; whether that is the debt incurred by working class law students and the conveyor belt supply of labour supply directed toward corporate law it produces; or that those with precarious migrant status are unlikely to be able to work in the UK after they graduate. The piece also foregrounds a discussion about the challenges of leveraging power in legal aid clinics

Political composition is an important element to workers’ inquiry and until very recently, there was no specialist legal workers union. Our interview with Casey* and Khadijah*, two members previously active in the Legal Sector Workers’ Union (LSWU) (a branch of United Voices of the World (UVW) union) reflect on their experience of organising in the legal sector within a large legal aid firm. As has been previously discussed, earlier attempts to establish a trade union had failed and much collective organising typically happens through professional associations. The political sensibilities that lawyers are typified as having, are some of the reasons which preclude their participation; as well as the high turnover of precarious legal workers. What emerges from their chapter is how the union began to break from the atomised nature of legal work places. Especially insightful were the challenges of organising in a legal aid-funded firm, bearing the bring of rapacious austerity since 2012 and would typically be servicing clients from working class backgrounds. What is also apparent is that LSWU, imbuing the ethos of solidarity strikes that were prohibited by the UK government in the 80s, also sought to use their platform to offer solidarity to their clients and various internationalist struggles.

Oliver Conway’s diarised contribution is part a day in the life of a high street legal aid lawyer, part eulogy to the high street firm. It puts the trials and tribulations of his clients against the working class background from which he came, ravaged with debt and spending his wages on exorbitant London housing. The references to his underpaid paralegal or the support staff are telling. Like Roger Bravo’s contribution, Conway identifies how they are the invisible labour or ‘unspoken contract’ of the high street firm, and in particular, the ‘extra limb’ of the legal work process. The irony is that the important work that social-justice lawyers like Oliver do, is less valued by the state. There is an inevitability therefore, in the demise of the high street firm. Conway also acknowledges the challenges that AI and automation pose, and the coldness with which this would mediate the otherwise humane and warmer textures of lawyer-client relationships.

Legal workers were the target of criticism from the previous Conservative government, castigated as ‘ambulance chasers’ or ‘lefty lawyers’. Isobel Bowler and Maxwell Goddard, both legal workers at the Greater Manchester Immigration Aid Unit, discuss ‘the negative political language’ directed at their work and the groups they represent, within the ‘hostile environment’ milieu. Anti-migrant rhetoric is, they write, ‘transferred to us as legal representatives’. In their piece, they examine how government and media rhetoric has made the work they do precarious and at times dangerous. This has led to attacks on their offices requiring heightened security measures as a result. However, the attacks on their clients and the work they do has fed into a solidarity between their co-workers. Though they are paid well, it cannot compete with the private sector, and the structural issues around granting asylum claims creates a significant absence in their representation or support.

Stan French*, a former legal aid solicitor, provides a vivid and intimate account of the effects of his workplace in a community care law firm on his personal wellbeing, that ultimately led him to leave. Weaving both narrative and facts, French illustrates the economic incentives behind legal aid for an area of law that is significantly underfunded. They show how rigid categories of law don’t match with the intuitive sense of rights that his clients have; and this can often be a source of intense workloads for lawyers. An important resource for bosses, writes French, is the good will of their workers that are committed to an area of law that is in the service of the made-poor and marginalised. Despite this, French concludes that the conditions are potentially ripe for unionisation.

The moral and political commitments of legal workers to the made-poor and vulnerable are an important repository from which bosses can exploit their workers. This underwrites Louise Lorde* discussion of their work as a human rights solicitor, representing vulnerable people in claims against the state. They outline how their work is organised, the main challenges in their workplace, and their attempts at union organising. They detail their labour process- from advising their clients, outlining their funding options, obtaining evidence, writing letters of claim, instructing experts, settling or taking to trial etc- and make reference to the pattern of class differentiation between solicitors and barristers. Louise’s journey is one which appears typical of working-class lawyers, working as an admin-paralegal to ‘get a foot in’, juggling several jobs and code-switching to ensure one is taken seriously. They outline the difficulties of unionising- including disaffection with bigger unions, workload- but discuss how through informal chats in the work space, they have been able to secure some small victories.

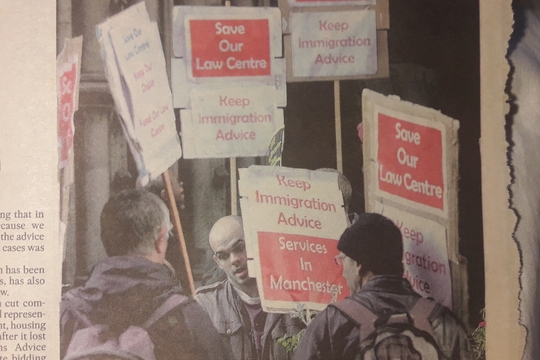

The 2012 cuts to legal aid did however, provoke much workplace organising. John Nicholson, a former immigration barrister, walks us through the recent history of resistance to cuts in legal aid in Greater Manchester. These austerity measures occurred, as he writes, because of a broader crisis in social reproduction, as well as more punitive immigration regimes and the creation of ‘advice deserts’. John speaks to more informal organising that took place to defend the closure of advice and law centres following the global financial crash in 2008. In similar echoes to Isobel and Maxwell’s contribution, the antagonism is not with bosses per se, but with local councils and the legal services commission that provide funding for immigration and social welfare law work. A combination of legal and political elements comprise the strategy to resist closures. John also refers to the creation of the Greater Manchester Law Centre, a centre which emerged from the ashes of several other law centre closures in the area, and which continues today as a fighting, campaigning organisation.

It would be remiss to not recognise the globalisation of UK legal services. Many of the bigger law firms for example, have established offices in key financial centres across the world. This has also led to the repatriation of certain work streams in UK law firms. Sreyan Chatterjee and Suddhabarta Deb Roy offer an important account of how the outsourcing of UK legal services to India has ‘become the crucible of experimentation in value capture, workplace control and domination over workers’ lives.’ In their fascinating piece, they explain how the rise of paralegals in India since the neoliberal reforms of the early 90s have produced a highly exploitable pool of labour. Through interviews with workers in Bengaluru and Mumbai, their contribution reveals the technical, social and political composition of the ‘legal process outsourcing’. Outsourcing has therefore led to a segmentation of the legal workforce in India, making organising difficult.

Some of the earlier essays make reference to legal education and the way in which it is structured to produced the kinds of legal workers that is the target of Lenin’s opprobrium. Kate Bradley tries to unearth the process by which well-intentioned law students that initially want to practise in social-justice oriented areas of law end up representing capital, through understanding ideology in law schools and her own experiences of how the sector perceives itself as ‘above the fray’. Foregrounding her experiential account, is a counter-analytical take on the work law does for capitalism, drawing on Marxist jurisprudence. The funding structure of legal education from university to firm, means that people will likely go in higher-earning areas of law to help ameliorate their debts.

In the final contribution to this book, Will Staveley, a facilities manager at chambers, brings into focus the unique technical composition and stratification of labour in his work place. Will describes how clerks and barristers, the former who take a cut of the barristers fees, are in a symbiotic but unequal relationship, given the latter outnumber and therefore obscure the exploitative relationship with the former. As he writes, several roles within the chambers are done on a voluntary basis, occasionally by barristers, but more likely that not, given the ebbs and flows of their practice, will likely mean these tasks are delegated to non-lawyers. Herein, we see Will write about the difference in labour entitlements between barristers and support staff pertaining to work spaces, maternity and menopause leave etc. Will also talks about how the incentive structure for clerks’ bonuses are tied to the success of the barristers work. The physical separation of certain types of staff (clerks and marketers for example) is not conducive to building solidarity, while the notion of the chambers as a ‘family’, he writes, can obscure the different social relations between clerks, administrative staff and barristers. One anecdote he provides, brings into acute focus the invisibilisation of the labour of clerks and administrative staff; and how gift giving, an age-old tradition at the bar, is often a way to pacify demands for better wages.

-

Lenin, Vladimir 1962 [1905], ‘A Letter to Y. D. Stasova and to the Other Comrades in Prison in Moscow’, Lenin Collected Works: volume 8, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. ↩

-

Grigg-Spall, Ian and Paddy Ireland (eds.) 1992, The Critical Lawyers Handbook: Vol 1, London: Pluto. ↩

-

Economindes, Kim and Ole Hanson 1992, ‘Critical Legal Practice: Beyond Abstract Radicalism’ in The Critical Lawyers Handbook: Vol 1, edited by Ian Grigg-Spall and Paddy Ireland, London: Pluto; See also Fitzpatrick, John 1992 ‘Legal Practice and Socialist Practice’, in The Critical Lawyers Handbook: Vol 1. ↩

-

Bellamy, Christopher 2021, Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid, https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/independent-review-of-criminal-legal-aid ↩

-

Though that is not entirely irrelevant. See also Law, legal practice, and capitalism. ↩

-

Notes from Below 2018, ‘The Workers’ Inquiry and Social Composition’, Notes from Below, 1. ↩

-

Stamp, Dave 2023, ‘Burnt Out’, Notes from Below, https://notesfrombelow.org/article/burnt-out ↩

-

See: https://www.unitetheunion.org/what-we-do/unite-in-your-sector/finance-legal ↩

-

See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-63198892 ↩

-

See: https://www.lccsa.org.uk/lccsa-and-clsa-members-joining-the-trade-union-unite/ ↩

-

Published in Pozzi, Francesca and Gigi Roggero (eds.) 2002, Futuro Anteriore, Roma: Deriveapprodi. ↩

-

Flood, John 2013, What do lawyers do? An ethnography of a large law firm, New Orleans, LA: Quid Pro. ↩

-

Fitzpatrick, ‘Collective Working in Law Centres’. ↩

-

Holt, Kim and Nancy Kelly 2020, ‘“Children not trophies”: An ethnographic study of private family law practice in England’, Qualitative Social Work, 19, 5-6: 1183-1199. ↩

-

Abel, Richard 1985, ‘Comparative Sociology of Legal Professions: An Exploratory Essay’, American Bar Foundation Research Journal, 10, 1: 1-79. ↩

-

Abel, ‘Comparative Sociology of Legal Professions: An Exploratory Essay’, p.6. ↩

-

See also Key Concepts. ↩

-

Abel, Richard 1988, The Legal Profession in England and Wales, Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ↩

-

Sommerlad, Hilary, Andrew Francis, Joan Loughrey and Steven Vaughan 2020, ‘England and Wales: A legal Profession in the Vanguard of Professional Transformation’ in Lawyers in 21st-Century Societies: Vol 1: National Reports 2020, edited by Richard L Abel, Ole Hammerslev, Hilary Sommerlad, and Ulrike Schultz, London: Bloomsbury. ↩

-

Notes from Below, ‘The Workers’ Inquiry and Social Composition’. ↩

-

Notes from Below, ‘The Workers’ Inquiry and Social Composition’. ↩

-

Bowcott, Owen 2019 ‘Barristers, solicitors and paralegals urged to join single trade union’, The Guardian. ↩

-

Madge, Nic 1978, ‘Unions in the Lawyers Office’, Bulletin of Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers, 9: 17-18. ↩

-

Haldane Bulletin 1983, ‘Unionisation of Solicitors Firms’, Bulletin of Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers, 17: 10-12. ↩

-

Sommerland, Hilary 2020 ‘England & Wales: A Legal Profession in the Vanguard of the Professional Transformation’, in Lawyers in 21st-Century Societies. ↩

-

See also Lewis, Thomas 2020, ‘The Legal Sector Workers Union’, Chambers Student. ↩

-

LSWU 2019, ‘A trade union for all workers in the legal sector’, Socialist Lawyer, 81: 5-6. ↩

-

Ricca-Richardson, Isaac 2020, ‘A Hell of Ride’, Socialist Lawyer, 86: 9-10. ↩

-

O’Connell, Paul and Umut Özsu 2021, Handbook on Law and Marxism, Cheltenam: Edward Elgar. ↩

-

Marx, Karl, 1861-63, ‘Digression: (On Productive Labour)’, in Marx’s Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63, Part 3, Relative Surplus Value, Volume 30, MECW, p. 306. ↩

-

Tronti, Mario 2019, Workers and Capital, London: Verso. ↩

-

Marx, Karl and Fredrich Engels 1848, The Communist Manifesto. ↩

-

Klare, Karl 1979, ‘Law-Making as Praxis’, Telos, 40: 123-35. ↩

-

Althusser, Louis 1971, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, New York: Monthly Review Press. ↩

-

Hugh Collins 1984 Marxism and Law ↩

-

Pashukanis, Evgeny 1980 [1924], ‘A General Theory of Law and Marxism’ In Selected Writings on Marxism and Law; London: Academic Press; See also Knox, Rob 2016 Valuing race? Stretched Marxism and the logic of imperialism; London Review of Internaitonal Law; 2024 was the centenary anniversary of his most popular treatise, Legal Form 2024, ‘100th Anniversary of “The General Theory of Law and Marxism”: Pashukanis@100’, Legal Form, https://legalform.blog/pashukanis-100th-anniversary ↩

-

Pashukanis, A General Theory of Law and Marxism. ↩

-

Abel, The Legal Profession in England and Wales, p.21. ↩

-

Abel, The Legal Profession in England and Wales, p.21. ↩

-

Bankowski, Zenon, and Geoff Mungham, 1976, Images of Law, Law Book Co of Australia, p.78. ↩

-

Pashukanis, A General Theory of Law and Marxism. ↩

-

Knox, Rob 2018, ‘Against Law-sterity’, Salvage Magazine. ↩

-

Abel, The Legal Profession in England and Wales, p.22. ↩

-

Abel, The Legal Profession in England and Wales, p.23. ↩

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Capitalistic Structures of the Legal Workplace

by

Roger Bravo

/

May 12, 2025