The Capitalistic Structures of the Legal Workplace

by

Roger Bravo

May 12, 2025

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

An account of the structure of legal work

inquiry

The Capitalistic Structures of the Legal Workplace

by

Roger Bravo

/

May 12, 2025

in

Legal Workers Inquiry

(Book)

An account of the structure of legal work

In writing this chapter I intend to explain how the typical legal workplace (independent solicitors) is organised, and examine the ability of workers in the legal sector to organise and support each other. The aim of any organising and support must be to promote working class representation at all levels within the legal profession with a view to all legal sector workers being able to enjoy the full benefits of their labour. If history teaches us anything, it is that the working class will drive any lasting change in society and that the middle and upper classes do not need to be handed any more advantages than those they were born with. This broadly accepted (among Marxists) formulation can be starkly observed in the legal profession.

Where I have referenced class, I have taken the ‘middle class’ as those with a ‘professional’ socio-economic background and ‘working class’ as those with an ‘intermediate’ or ‘lower’ socio-economic background. It is my belief that any definition of working class ought to be as broad as possible, within reason.

The typical legal workplace

From high street to multinational magic circle firms, the hierarchy in the offices of solicitors is common across all:

- Facilities & administrative (“admin”) support staff:

1a. Facilities - post rooms, receptionists, cleaners and reprographics

1b. Admin - secretaries, personal assistants and call handlers - Professional support staff - marketing, accounts, HR and IT

- Legal support staff - paralegals and junior fee earners

- Solicitors/Associate Solicitors

- Managing/Senior Associates

- Salaried Partner/Legal Director

- Senior support staff - Directors of Human Resources/Accounts/Marketing/IT1

- Equity Partner

- Managing Partner

The partnership structure in law firms makes equity partners investors and part-owners of the legal workplace, having injected capital (typically through a loan granted by the firm on favourable terms) into the firm. The idea is that they are able to draw (as a dividend or bonus) a portion of any profit with their invested capital potentially at risk if the firm collapses. Independent solicitors firms are most often set up as limited companies or limited liability partnerships.

This hierarchy is rigidly observed and keenly felt in most workplaces, particularly in commercial firms or those catering to wealthy private clients. Even firms that may be considered liberal/left-wing, tend to have the same structure, creating divisions between staff at different levels of the hierarchy, with legal skills rarely being shared with and developed by support staff. Any worker in the legal sector will be aware of a partner they have shared a workplace with who was completely unapproachable and/or routinely unpleasant to junior staff.

Facilities and Admin Support

Working class representation is strongest amongst the facilities and admin support staff. These staff members are often the lowest paid and many are not educated to degree level, although law graduates occasionally take these jobs as a first foot in the door. It is common for members of the support staff to have been with a particular firm for many years, and they are often considered the backbone of the firm, having a deep institutional knowledge of internal processes and politics. Senior personal assistants and secretaries (often female) will be said to be ‘running the firm’ as they are so crucial to the proper functioning of the business. Even where their level of skill and knowledge is recognised, they tend to remain in a poorly paid subordinate role despite the importance of the tasks they undertake and the ‘value’ that they create.

Professional Support

Professional support staff at the younger and more junior end, are often educated to degree level. Those at a more senior level are a mix and match of those with degrees, those with B-Tecs and, more rarely, those who have moved from admin and facilities to undertake a more technical role. In IT departments, there is significant scope for progression open to those who demonstrate talent, despite possibly not having professional qualifications. Wages vary from among the lowest at the firm to on a par with solicitors. Professional support workers are slightly more likely to be working class, with only 47% having a parent with a ‘professional’ occupation.2 Only 8% attended private school, less than half the equivalent figure for solicitors.

Legal Support

Legal support staff often constitute the majority of the employees at claimant firms (i.e. those who represent individuals rather than businesses). This is especially the case in firms focusing on Personal Injury (PI) and group claims (i.e. legal action brought by large groups of people).

Often young and having recently left university, paralegals are the group of workers most vulnerable to exploitation as they seek to gain experience and become a solicitor. Paralegals will typically not spend more than three years at a single firm, as this is part of their route to becoming a solicitor. The primary role of paralegals is to support solicitors in their work by undertaking routine legal tasks, such as dealing with clients and reviewing documentation. Some paralegals may be entrusted with their own caseload once they have sufficient experience or have demonstrated a particular aptitude for the work. Paralegals will, more often than not, be middle class. However, there is better representation of employees from a working-class background amongst paralegals than among solicitors.

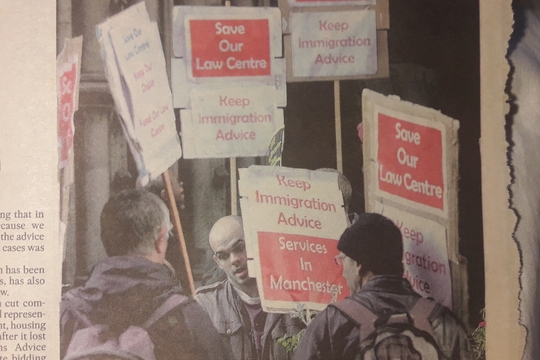

Fee earners, often seen in PI firms, are often non-degree-holding members of staff who are permitted to work on cases. They typically work on low-value PI and road traffic accident (RTA) type claims and will, more occasionally than paralegals, progress to becoming solicitors. They will often remain with firms for a lengthy period of time and are likely to be female, working class, and with caring responsibilities. Junior fee earners tend to be responsible for their own caseload under the supervision of a Senior Associate or Partner. Prior to the cuts to publicly funded legal advice, driven by austerity and codified in the Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (‘LASPO’), in 2013, law firms active in providing social welfare advice would have teams of politically engaged, knowledgeable, and experienced working class fee earners providing advice in areas such as immigration, housing, debt, welfare benefits and employment. Many of these people were made redundant as a direct consequence of LASPO and austerity driven cuts and have now left the legal sector, unlikely to return.

Legal support staff are typically paid slightly more than admin & facilities support staff with average wages between £20,000 - £30,000.

Solicitors/Associates

Solicitors and associates tend to be the most numerous staff at commercial firms. They are almost all educated to degree level, and those who attended university in the late 2000s tend to have some form of post-graduate level qualification. For the most part, solicitors will be in their late 20s to 30s, although some will go through their entire legal career as a solicitor/associate.

The majority of solicitors will have responsibility for managing their own cases to a certain extent, but will be dependent on a senior colleague to provide them with work from their sources. They will be required to assist in the management of client relationships. They may be required to conduct litigation and assist in managing paralegals and admin support staff within their team. An average solicitor will earn £65,000.3 however, salaries can vary from around £25,000 per annum at high street firms to £200,000+ at big city or US firms. Most solicitors will present as middle class and tend to suppress any regional accents or working class markers to be seen as ‘professional.’ Around 57% of solicitors come from what may be considered middle-class households with a parent having a ‘professional’ occupation.4 This statistic does not change significantly as seniority increases.

Managing/Senior Associates

A managing or senior associate will ordinarily have between five to ten years of post-qualification experience (PQE) as a solicitor. They are responsible for managing their own cases. They will be expected to generate some of their own work while maintaining a degree of reliance on a partner for supervision and the provision of work. They will have some responsibility for managing a solicitor, paralegals, and admin support staff. This role is often seen as a stepping stone to partnership. However, it may be given to solicitors who have demonstrated significant technical expertise and/or have substantial experience in a particular area of work. Those seeking to advance to partnership will be expected to show ‘commercial acumen’ by covering the costs of their own employment through their work and/or managing junior staff on behalf of an Equity Partner for a few years.

Salaried Partner

A salaried partner would typically have more than ten years PQE as a solicitor and a track record of being able to generate their own work sufficient to cover the costs of a team (see below). Most salaried partners will be responsible for the day-to-day and strategic management of a small team within a wider team. A small team may consist of two solicitors, two paralegals and a member of admin staff. A minority of salaried partners will reach the position by taking on responsibility for managing large numbers of paralegals/fee earners, this route to partnership can be seen in firms that concentrate on producing high-volume work (low-value PI or large group claims).

Salaried partners earn, on average, £75,000 per annum and may be involved in firmwide decision-making, having a vote at meetings of partners. There are significantly fewer working class partners than solicitors, and people who were privately educated are over represented at 25%,5 with this figure rising to around 61% of the cohort at one typical magic circle law firm.6 This does not compare at all favourably to a society wide figure of 5.9%.7 The figure for privately educated solicitors is 19%,8 reflecting that the networks generated by the privately educated make promotion to partner, particularly at City firms, much more likely.

Senior Support Staff

These will be the directors of professional services departments and may, occasionally, include a head of facilities, admin staff typically being managed by solicitors. Senior support staff will often be educated to degree level and be middle class. This is particularly the case in Human Resources and Accounts, where these are roles often involve some postgraduate professional certification. They may be part of a Senior Management Team (SMT) that will inform the direction of the firm. Salaries can be similar to those earned by equity partners, and within firms that have adopted an Alternative Business Structure (ABS) which permitted non-solicitors to join the partnership of firms following the Legal Services Act 2007.

Equity Partners

Once a salaried partner has demonstrated the ability to manage a profitable team, they may be invited to join the equity partnership and purchase a ‘share’ in the firm. Equity partners would usually have around 15 years PQE and have demonstrated a mixture of commercial and legal success. They are expected to have engaged in significant ‘business development’ activity, bringing in new clients to the firm and, at claimant firms in particular, generating innovative cases. Women are underrepresented at equity level, making up 53% of solicitors, with a cliff edge to 32% of equity partners. This inequality is often excused as being the result of women taking time off work due to caring responsibilities, but it is more likely due to a gender bias when it comes to promoting women to senior management positions.

Equity partners typically earn £130,000 per annum and will be involved in setting the firm’s strategic direction through votes at an AGM. They are encouraged to think of themselves as a small business within a business, often resulting in competition and strained relationships between teams employed by the same firm. The most ambitious equity partners will be responsible for departments, potentially incorporating multiple specialist teams headed by other equity partners. Some, whose ambitions know no bounds, may be responsible for running entire offices and dreaming of managing the firm.

Managing Partner

The managing partner is the big boss, equivalent to a CEO in a regular business. The managing partner has a multi-faceted role. They will manage the facilities and professional support staff, through the SMT, and set out a vision for the firm that is voted on by the equity partners at the AGM. Often, they will be assisted in setting out a strategic vision by the equity partners who are heads of departments. A managing partner at anything beyond the high street level will likely not carry out any specialist legal work, with their time taken up by their management role.

Teams & Departments

A department is typically headed up by a senior equity partner, and may consist of a number of teams with particular specialisms. For example, in PI there may be Catastrophic Injury, Road Traffic Accidents, Clinical Negligence, and Industrial Disease teams. A team will often be headed by an equity partner or occasionally by a salaried partner. This team leader will manage a budget, bring work in for the team and make decisions on recruitment. The next layer under the team leader is typically one or two senior/managing associate solicitors and two to four solicitors/associates. Depending on the type of work, there may be as many as eight paralegals or as few as two. Teams doing low-value and/or high-volume work will typically see a number of the solicitor roles replaced by paralegals or junior fee earners, undertaking a role that would historically have been the preserve of a qualified solicitor. There will ordinarily be at least one admin support staff member, often a skilled secretary or PA.

This team structure would typically be seen in all firms from medium to multi-national. A team broadly reflects the entire staff of a traditional high street solicitors’ firm and will often operate with a certain degree of independence from other parts of the firm. As small firms have consolidated, in light of various challenges squeezing the profit margins of legal services providers and an increased trend towards specialisation, most legal professionals now work at firms with multiple departments and teams. The traditional single-office high street practice, with generalist lawyers able to deal with all kinds of enquiries from the local community, is becoming a relic.

Competition and Industrial Organising

Due to the deeply entrenched hierarchical structures and stressful working environments, common to almost all law firms, the task of organising amongst working class members of staff is incredibly difficult. Almost all law firms base their profitability on ensuring that they have the correct ‘gearing’ (the ratio of partners to junior staff). This gearing is then multiplied by the number of hours worked, rates charged, the recovery of costs and profit margin, to give an idea of the profit each partner will make. The following examples are typical of such calculations and show the disparity in profitability between City firms and Claimant firms:

1 City

Gearing: 5 fee earners per equity partner

Chargeable Hours: 1,800 per fee earner per annum

Rate: £500 per hour

Recovery: 80% (£400 per hour)

Margin: 40%

Profit per Equity Partner (PEP) = £1,440,000

2 Claimant

Gearing: 5 fee earners per equity partner

Chargeable Hours: 1,200 per fee earner per annum

Rate: £200 per hour

Recovery: 70% (£140 per hour)

Margin: 20%

PEP = £168,000

This approach to ensuring profitability inevitably creates pressure on staff at all levels. Unless a partner has a reputation for particularly specialist knowledge in a complex area (e.g tax) for which they can charge enormous fees, the best way to make a profit is to push junior staff to produce a large volume of high quality work while keeping costs to a minimum. Beyond the longstanding structures which reward exploitation of staff, industrial organisation is increasingly required if we are to face the challenges of the future. AI and automation are key concerns, while AI cannot yet draft pleadings it can produce marketing copy, conduct low level research, be used to review disclosure and produce schedules of loss. These are all traditionally jobs carried out by those paralegals who, lacking other advantages, undertake labour intensive work as a first step on the ladder. We have also seen the beginnings of the offshoring of work to other jurisdictions with lower wages and less workplace protections. This will inevitably lead to redundancies, more competition between colleagues and a loss of opportunities for people wishing to enter the profession.

Competition Culture

A huge hindrance to organising in the legal workplace is the culture of competition and the reliance on an ability to ‘toe the line’ in order for people to progress, this is particularly prevalent during early career stages but does not diminish as workers move up the ladder into senior roles. A manifest example of the culture of competition is the importance to many legal professionals of being ranked in a directory, such as the Legal 500 or Chambers. It is difficult to imagine such a ranking system taking hold amongst architects, much less the release of the rankings being celebrated as part of their professional calendar, accompanied by mutual online back slapping and not so humble bragging.

This culture starts at law school. Students are encouraged to compete with each other to obtain the best exam results or coveted work experience opportunities. The ‘law society’ within a law school can be a breeding ground for future corporate lawyers. They are often run by a clique of students taking up positions on a committee and ensuring that they and their friends have greater access to the best career development opportunities to the exclusion of their fellow students. Anecdotally, these students seem more likely to be privately educated and tend to already have contacts within the legal profession who actively encourage their behaviour. It is rare that a 19 or 20 year old would seek election to a committee, without external prompting or a clear understanding of its potential benefits.

This spirit of competition is ramped up at law firms. Following their studies, a law student will often be required to do some work as a paralegal with a view to becoming a solicitor. In looking around at their peers in the office, every paralegal will know that there are more paralegals than solicitor vacancies. They must stand out from their peers (working long hours, attending social events and joining workplace committees) to have any chance of gaining a training contract. Paralegals can internalise a hierarchy of those who they see as more or less likely than them to obtain a training contract, attempting to improve their place within that internal hierarchy.

Outside of actual legal work there is a culture of patronage. Those paralegals with the best relationships with their bosses, in spite of talent or lack thereof, will be most likely to succeed quickly. The importance of the type of networking skills (which are, of course, promoted and taught in private schools) and adherence to unwritten codes of ‘proper professional’ behaviour will often be the difference between an early award of a training contract and several years of grinding and gaining experience and recognition.

This spirit of competition does not fade as legal professionals ascend the career ladder. It is just the beginning. Solicitors are often expected to bill and record hours with benchmarks set by reference to the performance of their colleagues. This encourages a harmful workplace culture of long working hours and high stress. It is not uncommon for negative comments to be made when someone tends to arrive and leave the office on time, regardless of their personal circumstances.

Those lawyers whose ambition is not sated by being one of those (un)lucky enough to become a solicitor will then throw themselves into competition with their colleagues at each stage of their careers. This means competing to obtain promotions and status within their firm and the profession. This culture of competition extends into the equity partnership, with the influence someone may exert on the direction of their firm often having a direct correlation with the amount of profit that they generate for their team/department in the first instance. Often, their contribution to the wider business of the firm is a secondary concern. It is not exactly as depicted in the TV drama Suits, but the partnership can be a ruthlessly cutthroat scene by the standards of most workplaces.

This hyper-competitive and individualist environment is antithetical to workplace solidarity. However, there are inspiring examples of professional services being delivered outside of the endemic capitalistic model outlined above. The co-operative model has been embraced in the legal sector by All Rise9 in the USA and has been attempted in accountancy in the UK by the Accountancy Co-Operative10 and adopted most successfully amongst firms of architects.11 The worker owned co-operative model may offer a viable alternative way of working in the legal sector.

A legal sector union

The most obvious answer for developing solidarity and class consciousness within the existing legal workplace is to unionise. Organising greater numbers of staff in non-managerial positions may effectively counter a hierarchical structure where power is heavily concentrated at the top and little agency for the majority of workers. An alternative or addition to joining the union is to join the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers. This organisation has a long and proud history of radical activism amongst the working class, particularly during the miner’s strikes of the 1970s and 1980s. Unfortunately, its activity outside of London is limited, with attempts to establish elsewhere not gaining traction. Particularly post Covid the move to remote work and away from in person meetings has had a more significant impact in the regions where there were less of these types of events in the first place. This prevents like-minded solicitors across the country from finding each other and beginning to organise collaboratively outside of the often stultifying atmosphere in union branch meetings.

In the legal profession, unions have not yet taken hold and do not appear well set to gain any momentum in the near future. It is likely that out of nearly 350,000 people employed in the legal sector,12 less than 3,000 (or 0.85%) are in a legal sector-specific union branch for lawyers and support staff. I am aware of only one recognition agreement between a union and an independent law firm at Thompsons, England’s long-established union firm of choice. This is not due to a lack of effort on the part of a number of activists within the sector.

Around 2011-2013, the early days of austerity and with LASPO looming large on the horizon, a number of left-wing lawyers urged forming a union in order to withdraw our labour and joined Unite. That project fizzled out as quickly as it started. The Unite legal branch was merged with ‘financial’ workers, becoming a place for those with ambitions in the Labour party, but with no real desire to rock the boat in the legal sector. Many of the members of this small branch, which merely existed on paper through much of the 2010s, were in senior positions within their organisations and the profession. Others impacted by LASPO, and aware of the benefits of a union, directed their energy into other forms of activism or left the legal sector forever.

In the late 2010s, as a consequence of issues in the criminal justice system, a new wave of young legal professionals were switched on to the need for the legal sector to organise within a union. This awareness arose due to the signal failure of representative bodies such as The Law Society and The Bar Council to represent and protect their members effectively. This resulted in the formation of Legal Sector Workers United (LSWU), a branch of United Voices of the World (UVW). Enthusiasm was high, and recruitment was solid, but the pandemic halted any rapid development. When things opened back up again, UVW made clear that they were focusing more on organising amongst migrant workers. What followed was a collapse in morale, a split and the diversion of a fair amount of radical DIY union energy into larger bureaucratic unions (primarily Unite and GMB). The various joyous actions aimed at organising the junior end of the profession have now ceased. The wind has left our sails, and the moment appears to have passed us by again.

It is worth highlighting that in all the attempts at union organising within the legal sector, it has proven incredibly difficult to bring support staff into the fold. This is despite concerted efforts by LSWU members in some workplaces. The split between support staff and legal workers must be overcome if a unionising drive is to improve pay and working conditions for all in the legal sector, not simply benefit those who have been privileged enough to attend university and obtain legal qualifications.

If, in the short term, developing a legal sector-wide union is not possible, workers with a developed political and class consciousness will have to take individual responsibility for improving their places of work. Useful action can be as basic as refusing to accept long working hours as the norm or as complex as organising fellow workers to ensure wages are increased each year to meet the cost of living. There are always opportunities to show workplace solidarity with fellow members of the working class. Where there is solidarity, there is hope.

-

Senior support staff are unlikely to be found at a high street firm. ↩

-

Solicitors Regulation Authority, 2024, ‘Diversity in law firms’ workforce’, Solicitors Regulation Authority, https://www.sra.org.uk/sra/equality-diversity/diversity-profession/diverse-legal-profession ↩

-

The Law Society 2024, ‘How much do Solicitors Earn?’, The Law Society, https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/career-advice/becoming-a-solicitor/how-much-do-solicitors-earn ↩

-

Solicitors Regulation Authority, ‘Diversity in law firms’ workforce’. ↩

-

Solicitors Regulation Authority, ‘Diversity in law firms’ workforce’. ↩

-

Lock, Simon 2019, ‘Magic Circle Partnerships’ Oxbridge and Private School Bias Exposed’, Law.com, https://www.law.com/international-edition/2019/10/29/magic-circle-partnerships-oxbridge-and-private-school-bias-exposed ↩

-

See also Independent Schools Council 2024, ‘Research’, Independent Schools Council, https://www.isc.co.uk/research ↩

-

Solicitors Regulation Authority, ‘Diversity in law firms’ workforce’. ↩

-

All Rise, https://www.allriselaw.org; All Rise, 2023, ‘Traditional Law Firms vs. Legal Cooperatives: A Simple Lesson in Economics’ Medium, https://medium.com/@AllRiseLegalCoop/traditional-law-firms-vs-legal-cooperatives-a-simple-lesson-in-economics-479995c9bdfb; ↩

-

Accountancy Co-operative 2024, ‘Accountancy Co-operative’, https://www.accountancy.coop/contact.html ↩

-

Chadha, Sahiba 2019, ‘Co-operative by design’, RIBA, https://www.ribaj.com/intelligence/employee-ownership-cooperative-architecture-practices-cullinan-studio-sahiba-chadha-rising-star-growing-interest ↩

-

Clarke, D 2024 ‘Number of legal professionals in the UK 2021-2024’ Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/319211/number-of-legal-professionals-in-the-uk ↩

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

author

Roger Bravo

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Introduction to the Legal Workers’ Inquiry

by

Jamie Woodcock,

Tanzil Chowdhury

/

May 12, 2025