Towards Disequal Transition: Notes on the Ecological Worker

theory

Towards Disequal Transition: Notes on the Ecological Worker

by

Joel Kilpi

/

July 9, 2025

The Coming Composition of the Ecological Worker

I

The tables have turned at the feast of culpability. Forget the individual consumption choices and the frustrating indecisiveness of policymakers. Cast aside the Anthropocene as the humans’ disastrous reign on Earth. The time has come to put liability on where it belongs. From now on, it is the relentless accumulation of capital and the social formation structured to guarantee its continuation which ought to be held responsible for the ongoing ecological crisis. Blame capitalism; capitalism and its expansionist logic; the capitalist mode of production that overburdens the planet’s ecosystems with grave consequences.

Clear as it seems, not everyone is convinced. On the far side of the crowd that has encircled capital and raves around the culprit waving torches in the air, we can, if we look closely, discern a fellow called Bertolt, ready to ruin the evening with some disturbing questions:

Capital, many times accursed for destroying the Earth, who raised it up so many times?

Capital needs to accumulate regardless of planetary boundaries. Who else gets accumulated?

Capitalocene defeated Anthropocene. Was there not even a cook on the scene?

Among those within the reach of Bertolt’s oration, the questions uttered initiate yet another reversal of perspective. All of a sudden capitalism, so keenly grasped as an overarching system of domination over all living, begins to lose aspects of its once so coherent appearance. Bertolt’s questions seem to hint there are forces within capital on which capital is dependent on; forces which are not mere victims of its rule but in a crucial position in enabling its day-to-day operation. And who knows, suggests some, perhaps these forces can have a will of their own; traits and quirks not easily bendable to capital’s order; needs and desires exceeding what capital can provide. As if the ancient names whispered in the tales of the old folks would come in the flesh right there, in Bertolt’s nightly summon. The crowd becomes restless. Is it the workers he is speaking of? The working class?

And this is where we begin. From these old words, from their possible new uses, from the paths they can show us on our journey from suffering a crisis into becoming one. In present times, where threats of unwanted catastrophes are many, we find in these words a certain notion of catastrophe to be most warmly welcomed. It is the notion of the working class as the catastrophe of capital.

II

At the core of the catastrophe lies a commodity called labour-power. This labour-power is “the aggregate of those mental and physical capabilities” that we as human organisms put to work whenever we produce something under capitalism.1 What makes labour-power peculiar among other commodities is its capacity to produce more value than is required for its own reproduction. We are during a workday able to produce more than is needed to maintain our daily capacity to work. The surplus produced, however, is not for us to enjoy, as it goes in the pockets of capitalists. This exploitation of surplus labour is what keeps capital going but simultaneously exposes it for notable dangers, as labour-power never comes to capital alone. Isolated as we may sometimes feel in the labour market, we are not in any circumstances on our own, since our labour is productive for capital only in relation to the labour performed by others. As workers we are always already a crowd, and the fact that we work together implies a potentiality to resist the working regime together, too. We face capital from the beginning as a collective subject of labour-power; as a working class; as a force capable of both producing capital and to subvert its command.

This is what capital has no choice but to deal with. If the supply of labour-power runs dry, capital is thrown into an existential crisis. It is only when means of production are used to organise labour-power to produce surplus-value that they become capital and their owners capitalists. Correspondingly, it is only through the relation with alien means of production that labour-power becomes labour, the bearers of labour-power become workers, and these workers are composed into a class. Capital is helplessly stuck in a position where its incessant addiction to labour-power keeps reproducing a force which carries a potentiality of dismantling capital itself by refusing to submit the commodity that capital so desperately needs. Capital’s manoeuvres to secure the availability of labour-power and their extension beyond the immediate point of production construct the historical conditions where the collective interests of capitalists as a class are depersonalised to traverse and shape the overall social relations of a given situation. Hence, we arrive at a capitalist society; at capitalism as a “historical system of the reproduction of the working class.”2 Looked at this way, it is not capitalism which divides people into classes from above and then positions these classes against each other. It is, on the contrary, the threat of working class withdrawal from the class relation between workers and capital which constitutes and remodifies capitalism as a social formation that is set to preserve, in differing manners in differing historical conditions, the productive encounter between bearers of labour-power and the means of production not in their possession.3

If the active part that the working class plays in the so-called “development” of capitalism is taken seriously, then the role of workers in the current ecological crisis comes forth as well. From the working class point of view, it is not the greed of capital which generates its persistent expansionism over the limits that ecosystems can bear, but the ever-present workers’ thrust within the class relation that obliges capital to indefinitely intensify and increase production. Much has been lamented on fossil capital, but from this perspective it would be more adequate to speak of the fossil working class. It is workers who produce in conditions supercharged by fossil energy; it is workers whose refusal to settle for what capital has to offer that makes fossil fuels so compelling for keeping the rate of exploitation bearable. Capital itself is nothing more than fossilised past labour, and the capitalist labour market a venue where the once living productive capacities of ours now stand in front of us in a mortified and alien form: as dead labour, that, “vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.”4

The purpose of this turn towards fossil working class instead of fossil capital is not to point out a new guilty party for the ecocide in a moralistic manner, but to seek means to organise against it which may not be provided by the approaches that take capitalist domination as a primary point of reference in explaining ecological destruction. Objectivism in the analysis of capitalism tends to lead into subjectivism in the attempts of contesting it. When capitalism is perceived as an all-embracing totality immiserating workers and the Earth from above in a deterministic manner, the capacities of fighting against it are often located beyond capital’s inner fractures to a domain of voluntarist politics. Hence, for example, the calls for “ecological Leninism” and “war communism” for taking hold of state power and for using it for sustainable ends, without much emphasis on the forces active within capitalism that could possibly carry out such objectives – not to mention if this kind of strategy represents the most desirable course of action altogether. Or then the hope laid on ecological sabotage of which reserves stem equally from a time and space detached from the material conditions of production. Here reformism pairs with extremism, and because both are adjusted to ignore the subversive potentialities within the everyday procedures that constitute capital, they are deemed to attack against it from the outside, equipped with not much more than the endless expositions of doomsday prophecies to feed the will of the activist cadre.5

As a class of workers, by contrast, we are never without leverage in the struggle against capital, because it is our productive input that enables capital to exist and operate in the first place. The actualisation of the potentialities this leverage entails; the transition from a force producing capital into its destructor, takes to recognise that the working class here in question is in constant motion. It cannot be reduced to some of its historical formations, such as factory or manual workers, nor grasped as a taken for granted revolutionary subject just waiting out there to be summoned to battle in the same manner in differing conditions. The worker revolts of yesterday do not automatically imply that the working class would rebel today, or that it would rebel now in the same ways that it has before. What the class struggles of the past can teach us, however, is that even if the relation between workers and capital would appear pacified today, nothing guarantees this to continue tomorrow.

The concept of class composition, developed within Italian operaismo in the 1960s, can be used as a tool to grasp the historically changing nature of the working class.6 As the name of the concept suggests, it provides a viewpoint to look at how workers are at any given time composed together in the production process and in its contestation. The concept is usually divided into two parts: into technical class composition and political class composition. The technical class composition refers to the productive qualities and techniques of governance presupposed at each time for the establishment and maintenance of the valorisation of capital. This comprises, for example, the skills and qualities required in work and the arrangements of productive cooperation, the methods of managing and disciplining workers, and the hierarchies that divide the workforce internally. The political class composition consists of the modes of thought and behaviour and collective action through which workers deal with or challenge their position in the order of production. This can mean, for example, various desires and aspirations for a better life, everyday gestures of grassroot disobedience, tendencies of mass insubordination, and practices of formal organising such as labour unions and parties.

The skills and capacities and the methods of governance exercised within technical class composition structure the side of the class relation which constitutes the working class as a productive subject; the acts of resistance conducted in the sphere of political class composition make the working class as a subject contesting the productive role imposed on itself in capitalism. Technical and political class compositions are hence two sides of a same class relation but oriented towards opposite directions. Technical composition consists of techniques that conserve the class relation; political composition of those practices which defy its formats and have, potentially, the capacity to dissolve the historical preconditions for the bond between dispossessed labour-power and capitalistically used means of production altogether. From this perspective, the history of capitalism appears as a series of different class compositions; as a changing combination of different kinds of productive abilities required in capitalist production and techniques of power to keep these abilities at work; and as different varieties of resistances and organisational attempts to challenge capital’s command or to break through from it.

By mapping the elements which constitute and contest the class relation, the concept of class composition can help in reinforcing workers’ capability to alter the historical conditions they are part of. Observation of technical composition makes visible how the governance over labour-power is arranged and upon what kind of hierarchies within the workforce it rests on, and can thus identify opportune areas for the attempts to dismantle capital’s rule over workers. Becoming acquainted with the political class composition, that is, with the capacities of resistance that emerge from the working class in a determinate moment, makes it possible to build the initiatives of organised struggle on the basis of the already existing insurgency instead of drawing these initiatives out of nowhere or copying them directly from the repertoire of past labour movements.

For the framework of class composition to function properly in organisational attempts within and against the current ecological situation, some re-evaluation of the approach is needed. The concept of an ecological class composition can be inserted to grasp how workers’ productive efforts and acts of insubordination are situated in the web of life. “Ecological composition” addresses the ways in which our productive capacities and their deployment in the production process (technical class composition) are at any moment in time enabled by the ecosystems we are part of, and then looks at how our labour correspondingly shapes the environments which we as productive organisms stem from. Our resistance against the working regime and our aspirations for a better life (political class composition) come to be equally viewed from the perspective of how our struggles and desires are presupposed by the ecological carrying capacity of a given moment. The lens of ecological composition illuminates the environmental preconditions and impacts of our work and of our fights against the order of production, and can hence be used to sort out tendencies within the class struggle that lean towards more sustainable futures. That is, towards futures where our work and our striving for better life does not make it unbearable to live on the Earth.7

III

Within the history of capitalism, work has always been “ecological”. It has on every occasion been performed as a part of a historically specific network of living and non-living things which enables work to unfold, and which is then correspondingly altered by the work done within it. As workers we are products of an environment that we constantly produce ourselves. In contemporary times, however, the ecological aspect of work has become perhaps more pressing than ever. The ongoing planetary crisis calls for significant rearrangements in work’s relation to the rest of the environment. The need to reorganise work towards more sustainable directions brings forth a character that is in the forefront of the aspired environmental change: the ecological worker. The figure of the ecological worker regards here all of us whose labour-power is put to serve the valorisation of capital within the overall capitalist production at the age of ecocide. Understood in this way, the ecological worker cannot be narrowed down to refer only to those who work, for example, in industrial or manual labour, nor to a group of workers in some specific industry which is considered to have a strategic environmental significance, such as in the production of energy. There are obviously differences in how our labours situate within the overall environment, and the restructuring of the labour done by some could have more direct consequences for the functioning of ecosystems than the rearrangement of the labour of others. But the interconnectedness of different work processes under capitalism implies that when it comes to the ecological destruction caused by capitalist production, we are all in it, as we are in the potentiality of preventing the destruction, even if in varying ways.

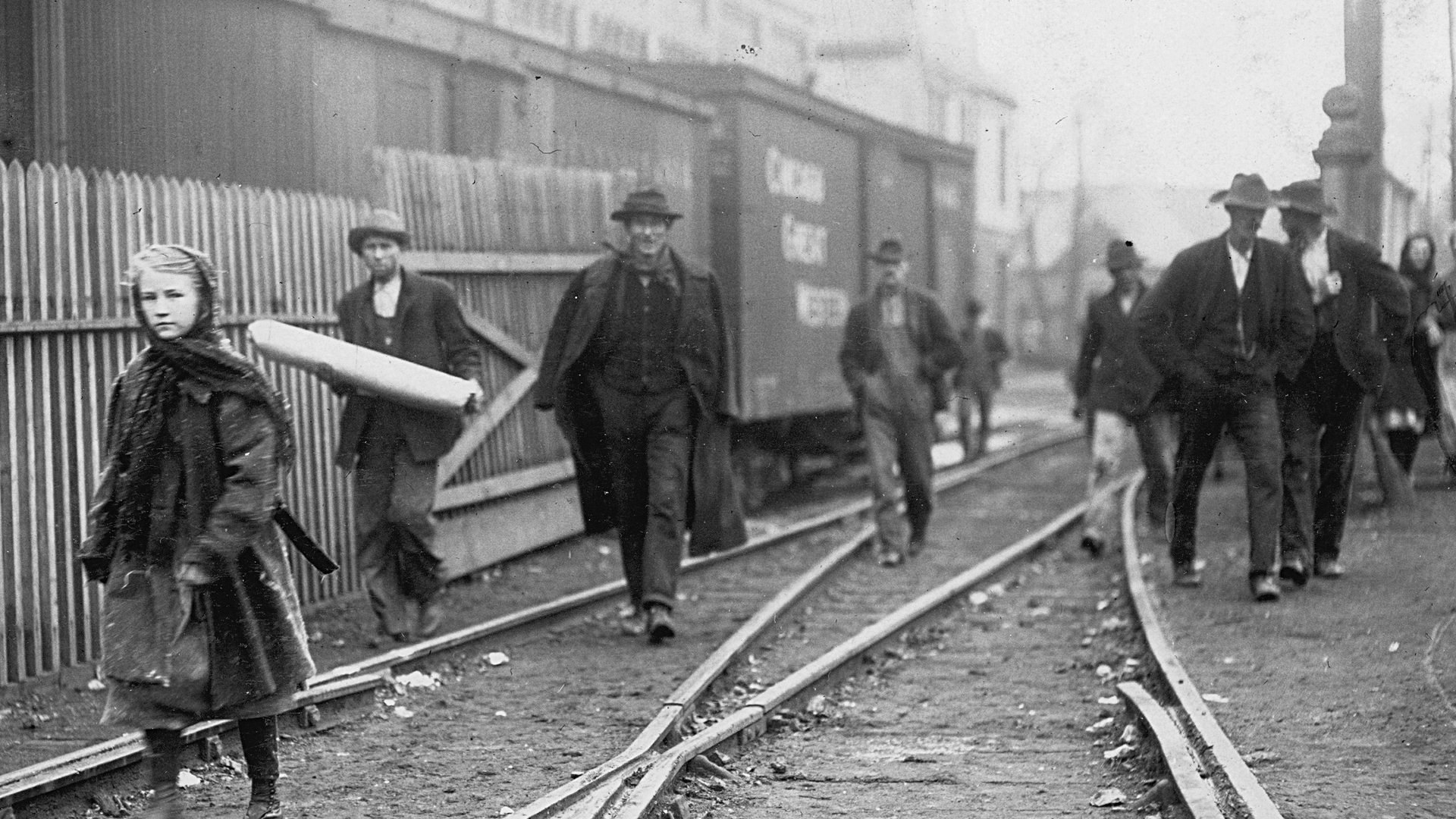

The combining factor that composes the contemporary workers of different character into a class of ecological workers is the imperative to produce on a scale that is unbearable for the rest of the environment and hence also for the workers themselves, as it is this same environment from where we as workers live in and from. The industrialization once brought the proletariat together in factories where they formed a distinct class of industrial workers that both produced industrial capital and positioned themselves as its gravedigger. Now the current environmental crisis constitutes a situation in which workers of the present are assembled into a global greenhouse where we are forced, in order to make a living, to work in conditions and in pace that endanger the living conditions of the planet – and, if we don’t want our work to degrade the environment and our lives, also to struggle against this same noxious regime of production that makes us the gravediggers of Earth’s habitability.

A further common denominator of the class of ecological workers is forged in the initiatives of green transition launched by capitalists and their servants in state institutions. In these initiatives, the ecological worker plays the role of an executor of programs where those who govern production from above pursue a more sustainable work regime by modifying the nature of the labour process and the usage of non-human resources within. Here the consumption of raw materials and energy sources and the waste management of production are put into transformation, but capital’s ascendancy in subjugating labour-power and non-human nature is left untouched. This ecological perestroika and the promises of capitalism with a green face it entails may help in slowing down the environmental crisis, but does not remove the threat that the expansionist logic of capitalist production itself poses for all living. And while the programs of green transition dictated by the powers that be seem not to undo the existential insecurity related to environmental destruction, they can add other kinds of insecurities to the lives of ecological workers. For some the green transition can mean new opportunities to work in healthier and more sustainable conditions, for others a loss of job and income and possibly also a deprivation of a sense of social belonging and worth attached to a kind of employment that is about to diminish in ecological restructuring.

In addition to the different positionings within the green transition, the field of ecological labour is divided and stratified in other aspects too. There is, first of all, the question of what kind of activity is recognised as work and remunerated with a wage and what kind of activity is not. The existence and reproduction of everyone’s capacity to work is from the beginning dependent on the care work that takes place in the sphere of home and social relations beyond the site which is traditionally understood as the workplace. The lack of wage for this kind of work that produces and reproduces labour-power – the most precious commodity for capitalist production there is – means that capital gets this work for free. Wage, in other words, conceals the real length of the working day. Through the wage, capital borders one part of productive activity to the limits of the working day but still benefits from the work that happens outside of it without paying for it.8

In so-called post-industrial capitalism, a notable part of production relies on communicative and affective abilities of which usage spreads over the sphere of wage labour to the whole of society. These cooperative skills come prior to the capitalist arrangement of production. They exist and develop outside of it, in the area of social, unlike in industrial production where the required skills were more a consequence of the capitalist organisation of the work process. Here productive labour accounts not only to the work that valorises capital in wage labour but also to the activities which produce the area of social as a resource and as a means of production. In the historical conditions where our everyday acts of social bonding come to be weighted as a resource pool for capitalist extraction, it is not only some human attributes that are put to work but the human organism as such with all its communicative and affective abilities.9

Even if our productive activity outside wage labour does not always generate directly visible transformations in the material environment – or no other products than ourselves as human beings and our ability to produce and keep producing – it is no less ecological than any other kind of work. The care we give and receive and the networks of our social cooperation rest on the ecological resources that comprise the non-human materials necessary for human life. The value and hence power capital extracts from unpaid reproductive work and social cooperation enables capital to tighten its grip over all living. If capital’s noxious rule on Earth is to be abolished, capital’s means to suck vitality from our lives must be confronted also beyond wage labour.

IV

The composition of ecological workers is as global as is global capitalism, but there are evident divisions between workers of different locations and positions within it. As is often repeated, the economies of the so-called Global North are responsible for a major part of the emissions that cause climate change while the most severe impacts of it are at the moment experienced in the so-called Global South. The work that we do in the North is both grounded on and on its part facilitates a way of life that can be called an “imperial mode of living”,10 where the affluence of the societies of the North is in significant parts constructed through an unsustainable appropriation and utilisation of the resources of the rest of the world. This stands for the capital-driven green transition too: the minerals needed for the ecological restructuring of the North are often extracted from the terrain of the South, which acquits the North from dealing with the environmental impacts of mining.

Following the fact that the effects of the climate crisis hit the hardest to the Global South, the advocates of “climate justice” in the Global North sometimes pinpoint the primary field of climate struggle to lie in the South as well. But from the perspective that highlights the ecological worker as an enabler and a potential challenger of the productive regime that generates environmental destruction, this kind of outsourcing of conflict to the South represents a misfortune negligence of the leverage in our hands here in the North. It leaves us with the inhibited role of a sympathiser, of a supporter, of an ally; with an inclination to project our striving for a better life to surrogate struggles that are always fought beyond our own immediate sphere of living. If it is the work we do in the North and the mode of living it constitutes that is the main factor behind the global climate crisis, we can do no better than to fight against this work wherever in the North we happen to be based. This does not exclude the importance of enhancing solidarity between North and South, but here the quest for ecological internationalism stems from the reciprocal need to build points of connection and mutual aid to strengthen the struggles that are being waged in different parts of the globe.

In addition to global divisions, the composition of ecological workers is stratified also within both the North and the South. Money and possibilities distribute unevenly across the workforces of global labour markets. It seems clear that the mode of living of the global well off consumes the environment more than the one of those with more modest wages or those who barely survive with their income, while the livelihoods of the latter ones are often more vulnerable in front of the measures of green transition programs. In the face of this, the leftist discourse of “just transition” has called the ecological restructuration of production to be sensitive in not pushing into deprivation the workforce which is put to go through it. Here the green transition is still held in high importance, but it is demanded to be carried out in a way that does not increase social inequalities.

But does this leftist plea achieve what it aims to, that is, to both protect workers from hardship and to guarantee a smooth progress for green transition? It looks likely that it doesn’t, in either case. When the left speaks of justice and inequality, it tends to do this from the viewpoint of bourgeois society and the norms it sets for a valued life. The mode of living facilitated by wage labour is taken as an eternal standard for all, only to be made a little more welcoming so that the lost sheep deviating from its average can be shephered safely to the promised new eden of just dispossession and equal exploitation. What gets missed here is the autonomy of the working class in setting its own values and objectives which do not necessarily match with the ones of the bourgeoisie. Without this autonomous capacity of the working class and the potentiality of dismantling capitalism it entails, the green transition cannot be anything else than capital-driven, and hence not green and sustainable enough, given that capital’s imperative for never ending growth and expansion appears not to fit to a planet with a limited carrying capacity. And even if the left would be content in operating within the boundaries of green faced capitalism, the failure to grasp the autonomy of the working class translates into an incapacity in building a force capable of compelling capital and state into concessions and hence in safeguarding a decent standard of living through the so-called “green” transition.

When the left demands a “just transition”, it acts like us workers would have lost every piece of our agency in determining how the ecological class struggle is fought. The “just transition” plays here as just another phrase for handing the initiative over to bosses and state authorities. The green transition of production gets accepted as a necessarily top-down process that only has to be made “fair” for the workers, who in this design are granted the role of mere passive recipients of what is at each time thrown at them. And as it happens that the hopes of “fairness” are not met – as it usually does – all that is left are the bitter but oh so righteous cries for “justice”.

Enough with this miserable cult of victimhood. Enough with the equation of working class desires to bourgeois metrics of fairness. To counter the leftist discourse on inequality which tends to treat divergences from bourgeois valuations as deficiencies that need to be neutralised through social inclusion, we turn to a concept of disequality which refers to an active refusal of evaluating our lives on the basis of what is at each time esteemed by capitalist society. The bourgeois way of life has brought the Earth as we have known it to the brink of terminal crisis. There is nothing in that shit to plead to be equal with, no justice but the one that is granted by the interminable subjugation of our world-making capacities under the rule of capital.

Our green transition is disequal. A disclusion of expectations from bourgeois sociality and a proud affirmation of proletarian difference. A de-integration from work that is making the planet uninhabitable and a constitution of new modes of being that know no common denominator with the ones of capitalist civilisation.

V

The material groundings of the strived for sustainable forms of life are, we have to admit, still to be found from the present conditions of production. The technical class composition refers to abilities that make us productive subjects for capital and to means deployed that keep us subordinate within its regime. At the same time, however, the technical composition points to skills and cooperative capacities that bear within them a possibility for new worlds, where our productive potentials would be used to other ends than serving the perpetual accumulation of capital.

Herein lies the only utopia we know and care of. When they come to repeat, again and again, that “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism”, we reply that we do not have to imagine either. The end of the world is already here, it is in our hands that make forests burn and glaciers to melt, as is the end of capitalism, right there among us in the class, in the potentiality to live and produce without capital, in the tendencies within the class that orient to break free from capital’s command and from the class relation itself. When they say there’s a need for “political imagination” to outline alternative futures beyond capitalism, we say that the imagination we are after regards the capacity to sketch organizational tactics that could nourish the futures sprouting from the here and now of disobedient grounds of living labour.

Over the past years we have heard numerous stories of people who rearrange their lives to have more space and time for environmental activism. Studies have been lightened or ceased, careers given up, work refused. In addition to the dedication to activism that it enables, this act of defection from work-oriented life can be taken as a form of environmental struggle itself. When we take distance from the life courses that make us successful persons in the eyes of capitalist society, we undermine capital’s capacity to harm the environment through our labour. This is degrowth from below: a downshift in the power of capital, an uplift in the time and energy to build modes of living that escape its order.

One may point out that the refusal of career and work-oriented life is a marginal phenomenon and a realistic option only for a small minority who can afford to make such a move. And maybe this is at the moment indeed the case. But one can also take the explicit examples of career defection as a visible peak of a wider development emerging beneath the surface. The current ecological situation makes the old certainties of studying and working tremble. Securing a position in the labour market does not guarantee a steady life to the same extent as it perhaps once did, as it is exactly our work and the mode of living it facilitates that endangers any kind of vision of a stable future. The anxieties raised by this state of affairs rage all over in the contemporary forms of life. We are defectors restless to get going, looking for freedom over the walls of employment offices and career planning centres, but there is yet no firm land in sight where to defect to.11

In this situation, the task of the organisational initiative of the ecological worker would be to generalise the urges to desert the bastions which oblige us to sacrifice our lives and the planet to work. To organize conflicts where the desire to liberate our capacities from the pliers of career would gain a mass character. To formulate demands that would articulate a framework for a worker initiated green transition; demands that could consider, for example, a drastic reduction of work hours and a basic income that would guarantee material protection through the ecological restructuration of society and function as a resource to experiment new sustainable forms of production. A struggle for basic income, if launched not just as a technocratic demand for a social policy reform but as a wage struggle that makes the unwaged work we do outside wage labour a visible point of conflict, would also undermine the strict binary of work/non-work that helps capital to leech in the unwaged reproductive work and social cooperation we engage in.

An organisational approach such as this diverges from the mainstream line of contemporary environmental movements of the Global North, of which main focus can be said to have been in putting pressure on policymakers in the chambers of institutional power. Most of the numerous blockades, sit-ins and other forms of direct action of the past years have had a more or less shared common objective: to hasten the environmental reforms executed through governmental bodies. As understandable and perhaps also necessary as this kind of way of proceeding is, it tends to truncate the space of change making to the sphere of institutional politics. When the planning and carrying out of ecological restructuration is mainly reserved for state authorities, the agency of the movements is reduced to a subsidiary role of trying to impact these authorities – the so-called “decision makers” – from the outside. In the worker initiated green transition, by contrast, the point of departure is not the field of bourgeois state institutions situated above us, but the abode of production that enables these institutions to function in the first place. On the level of this abode there are no other “decision makers” but ourselves as workers. The thrust towards sustainability develops from below; from the workers’ love for good life and from the hatred of the noxious regime of work that stands in front of it. Here we find a transition which does not descend from the governmental institutions to the rest of society but a one that, in a reverse order, ascends from the point of production to the overall social relations and then finally onto the plane of the state; and which, because it carries within itself the productive and antagonistic force of living labour on which the capitalist social relations rest on, holds the keys to compel the bourgeois state into green reforms, or better, to dismantle it for good, to make way for new institutions which are not constructed from the need to safeguard the accumulation of capital but from the urge to secure habitable living conditions on Earth.

A way to proceed that builds up from the desires for better life might also help in getting rid of some of the sad passions that have for so long plagued environmentalist sentiments. The environmentalist discourses are often characterized by a tone of reduction, abandonment and restriction. The demands for emission cuts or changes in lifestyles are presented as sacrifices that must be made to protect the environment. This strategy of renunciation seems to be based on an expectation that scientific evidence on the unsustainability of contemporary modes of living would oblige policymakers and people in general – if they just get persuaded enough – to take ecological issues more seriously and then to act accordingly. And when this does not take place, when no amount of information on the current and coming impacts of the environmental crisis appear to be sufficient in changing the course, what remains is moralistic indignation and resentful guilt tripping.

This deadlock takes place within a setting in which ecological destruction is posed as a cause that obligates interventions into the ways how people live their lives. A way out points to a reversal of order where we begin from the state of our living and then approach the environmental crisis from the perspective of making our lives better. This reversal of order would not reduce the importance of ecological matters, but positions the environmental crisis as an obstacle for our life forces, not as a starting point dictating their course. From this point of view, it is not the resisting of the environmental crisis that instructs us to live in certain manners, but our conception of a good life that necessitates fighting against ecological destruction. Here we are aligned with an intuition that a desire for a better life is in its joyfulness more powerful than a life driven by duty and guilt.

VI

The histories of western labour movements teach us that the arrival of new subjects of production and resistance – such as the ecological worker – can sometimes entail a direct contestation of the older worker figures and their organisations. The “industrial worker”, for example, was in the early twentieth century championed by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) as an ascending revolutionary subject that posed a serious challenge to the position of the “craft worker” in the hierarchy of production. Assembled together by the increased mechanisation of production as a figure of labour-power with no specific set of skills required in the labour process, the industrial worker did not have a similar social position determined by profession as the craft worker did. In the conditions of rapid mechanisation, however, the IWW considered the productive significance of the industrial worker to be on the rise and the one of the craft worker to be in decline.

Prominent amongst the ranks of industrial workers were people positioned at the lower ladders of the North American social order of the time, such as black, immigrant, itinerant and women workers. The revolutionary industrial unionism advocated by the IWW was presented as an organisational form for those who had not much to lose but all the world to gain, whereas craft unionism was portrayed as a mode of organising for those whose position in society was threatened by mechanisation and the new workforce coming into the labour market in its wake. The struggles of the IWW were hence thought to contest the old order, and the struggles of craft unions to defend it.12

A somewhat similar setting can be found in the emergence of the “mass worker” to the field of open class struggle in 1960s Italy. The mass worker was born at the assembly line in repetitive and massified factory work where all the work performances that could once have constituted a recognisable trade had been shred to pieces by automation. This contrasted the mass worker with the “professional worker” whose specialised skill deployed in the labour process made possible a certain kind of established position in industries. In general terms, the mass worker gave work only instrumental value or openly loathed it, whereas the professional worker took pride in craft, and by this aligned with the work ethic celebrated by the then prevailing labour unions and parties.13

A major proportion of the mass workers of the North Italian industries was comprised of immigrants from Southern Italy. In the eyes of the mainstream of the official labour movement, this unsteady subject uprooted by both the monotonous factory work and the itinerant status in North Italian cities did not carry a revolutionary potentiality. The mass worker did not show much interest in the traditional iconography nor even in the organisations of the old labour movement and was hence perceived to lack an adequate “class consciousness” for fighting capitalism. Due to its distance from the official labour movement and in line with the humanist Marxism prominent at the time, the mass worker could be lamented as an “alienated” figure inclined more to consumerism than to organising matters.

This standpoint on the mass worker was, however, not shared by all. The writers and militants gathered around the journals Quaderni rossi and Classe operaia and over time labelled as “operaists” saw in the rootlessness of the mass worker a tendency towards autonomy from capitalist production and sociality. If the mass worker really was “alienated”, this alienation contained a potentiality for an active and positive estrangement from the order of exploitation. And from the Piazza Statuto revolt of 1962 to Italy’s hot autumn of 1969, the mass worker indeed turned out to be truly capable of organising such an estrangement – and at times to a great dread for the officialdom of labour unions and parties.

Compared to the industrial worker of the early twentieth century and the mass worker of the 1960s, the ecological worker of the 2020s does not face an opponent such as the craft and professional worker beyond its own ranks. Instead, the dividing line between the emerging worker subject that poses a challenge for the prevailing order and the worker subject that aims to preserve the status quo, and its own established position in it, goes through the ecological worker itself. The inclinations of defecting towards more sustainable modes of living and the tendencies of sticking with the prevailing ones traverse our lives, both collectively and individually. But the orientation on the line of sustainability is not a matter of mere choice. It is conditioned by the ingredients for a dignified life at hand in a determinate moment. This is not only a matter of what kind of modes of living open up in a given situation, but also of our different positioning in hierarchies that shape our possibilities to grasp the chances each time available. We situate differently within the class based on how our differences in terms of, for example, age, gender and race facilitate our role in the hierarchy of production and in its contestation.

One clear point of division unfolding across the ranks of ecological workers stands out as generational. It appears – on average – to be more difficult for older people to re-evaluate their way of life and the work that enables it in the face of the environmental crisis. If a lifestyle and a social status have been for a long time guaranteed by a certain kind of employment, the threshold for defecting from unsustainable forms of working can be high, despite the possible concerns on climate change and biodiversity loss one may share. Younger people, on the contrary, have the privilege of not being accustomed to the prevailing modes of working and living in decades of participation in fossil fuelled capitalist production. It can be easier to refuse a career when you have not ever started one.

Another apparent factor causing breaches within the ecological class composition in the global north is determined by gender. The rearrangements and restrictions in the human use of the rest of the environment, and hence in the way how production is constituted, seem – on average again – often harder to swallow for those who are categorised as men in the contemporary gender order. In a situation where dominant masculinities have for long been partly constructed through patriarchal control over non-human environment, the initiatives contesting this control can come out as a threat for men who benefit from the patriarchal organisation of environmental relations. It looks therefore inevitable that the attempts to confront the working regime resting on patriarchal commodification of the environment will come to face the objections of men who are feared of losing their position in the social hierarchies of capitalism.14

In the midst of crisscrossing tendencies across the ecological class composition, the organisational initiatives to generalise the inclinations towards defection arrive at a question regarding the relation between the ecological worker and the prevailing institutions of the labour movement. Are contemporary labour unions and parties adequate for enhancing the strength of those currents within the class that strive for a sustainable subversion of the working regime, instead of preserving the positions of those worker groups who are satisfied with their position in its hierarchy? Or are the old worker organisations irreversibly adjusted to safeguard the concessions drawn from the unsustainable utilisation of environment (humans included), and hence incapable to do more than to negotiate the share of plunder within the limits of the existing ecology of production? If the latter, the new organisational forms of the ecological worker will have to fight not only capital, but also the labour movement institutions that inhibit the developments of mass defection.

In the attempts to speed up green reforms within capitalism and to contest capitalism altogether, it is not uncommon that environmental movements seek allies from workers and organisations representing them. Despite the examples of successful alliances between environmental and labour movements, it is equally common that those aiming to bend the perceived power of labour movements for environmentalist causes find themselves disappointed. The labour union structures, built for other kinds of purposes than dealing with ecological issues, can turn out to be slow or impractical in fostering sustainable change. Or the union administration or membership, or the perceived workforce in total, may become hesitant to heed the environmentalist call in the first place.15 The concept of ecological worker blurs the division between environmental and labour domains, and therefore might help in avoiding such disappointments by putting into question the need to approach “workers” as separate entities from the environmental struggle. If environmental activists urge to connect with workers, they can most likely start from themselves, taken that they too need to make a living in a society subjugated for the valorisation of capital, and contribute, in one way or another, to the unwaged reproductive work and social cooperation that enables the capitalist mode of production to function. And if we look at the environmental movements of the past years and decades from this perspective, it seems clear that a vivid and visible part of the workforce is not hesitant to fight against ecological destruction and for a sustainable mode of living.

However numerous the forces pointing towards an ecological defection are, the obstacles ahead seem enormous. The currents within the ecological workforce that cling to the fossil way of life cannot be said to be decreasing in magnitude. Even if the severeness of the state of the global environment can make it tempting, the premonitory consciousness raising is most likely not sufficient on its own to make a sustainable change within the ecological class composition. But what environmentalist education cannot teach, struggles of the ecological worker perhaps can. If the organised initiatives of ecological class struggle would manage to open up a horizon where workers’ strive for better life conjoin with environmentalist objectives, this could have impacts back to the political class composition as a whole. That is, if the ecological workers’ struggles were able to demonstrate the potential for a transition where, for example, the reduction of work hours, a green basic income and a quest for taking over the means of production are not only paired with but also manifest themselves as measures that slow down the environmental crisis, the aspirations for good life that emerge from the workforce as a whole might take a turn towards more sustainable directions. The alteration of course would in this case result not from converting people to support some environmental program or goal, but from organising conflicts which materialise the possibility to transform our lives in manners that both cultivate our autonomy and cherish the environment we live in; from conflicts through which we can experience the world and the preconditions of acting within it in novel kind of ways.

It is in the distant clamour of these coming struggles that we can, already, hear the wind of change blowing.

-

Karl Marx, Capital, A Critique of Political Economy, Volume One, translated by Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin Books, 1976), 270. ↩

-

For a conception of capitalism as “a historical system of the reproduction of the working class”, see Mario Tronti, Workers and Capital, translated by David Broder (London: Verso, 2019), 222, and Mario Tronti, The Weapon of Organization: Mario Tronti’s Political Revolution in Marxism, translated by Andrew Anastasi (Brooklyn, NY: Common Notions, 2020), 177. ↩

-

For a perspective highlighting working class struggles as a motor of development for capitalism, see Tronti, Workers and Capital. ↩

-

Marx, Capital, Volume One, 342. ↩

-

For example, in the widely read work of Andreas Malm, the historical role of workers in shaping capitalism so marvelously captured in Fossil Capital (London: Verso, 2016) seems to be unfortunately mostly forgotten in Malm’s books addressing the contemporary ecological conjuncture, that is, for example, in The Progress of This Storm (London: Verso, 2017), Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency (London: Verso, 2020), and How to Blow Up a Pipeline (London: Verso, 2021). For a more thorough critical scrutinisation of Malm’s oeuvre, see Bue Rübner Hansen, The Kaleidoscope of Catastrophe - On the Clarities and Blind Spots of Andreas Malm (Viewpoint Magazine, https://viewpointmag.com/2021/04/14/the-kaleidoscope-of-catastrophe-on-the-clarities-and-blind-spots-of-andreas-malm/, 2021), and Between Sabotage and State Power (https://buerubner.medium.com/between-sabotage-and-state-power-147120ac9176, 2023). ↩

-

For operaismo and the concept of class composition, see, e. g., Steve Wright, Storming Heaven: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism (London: Pluto Press, 2017). ↩

-

For the concept of ecological class composition, see also Nick Dyer-Witheford, Bue Rübner Hansen, and Emanuele Leonardi, Degrowth Communism: Part III (PPPR, https://projectpppr.org/populisms/degrowth-communism-part-iii). ↩

-

See, e. g., and especially for an emphasis on the positioning of women in the unwaged reproductive work, Mariarosa Dalla Costa & Selma James, The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1972); Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012). ↩

-

See, e. g., Antonio Negri, The Politics of Subversion, translated by James Newell (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989); Antonio Negri, “Interpretation of the Class Situation Today: Methodological Aspects”, Open Marxism, Volume 2: Theory and Practice, edited by Werner Bonefeld et al. (London: Pluto Press, 1992); Antonio Negri, Marx in Movement: Operaismo in Context, translated by Ed Emery (Cambridge: Polity, 2022); Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life, translated by Isabella Bertoletti et al. (London: Pluto Press, 2004). ↩

-

Ulrich Brand & Markus Wissen, The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism, translated by Zachary Murphy King (London: Verso, 2021). ↩

-

The discussion on defection here has been influenced by KAMV, Eriarvoisuuden puolesta, oikeudenmukaisuutta vastaan (Komeetta, https://komeetta.info/2025/02/06/eriarvoisuuden-puolesta-oikeudenmukaisuutta-vastaan/, 2025). ↩

-

See, e. g., Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Volume IV: The Industrial Workers of the World, 1905–1917 (New York: International Publishers, 1965). ↩

-

See, e. g., Wright, Storming Heaven. For the difference of alienation and estrangement in the operaist lexicon, see, e. g., Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy, translated by Francesca Cadel and Giuseppina Mecchia (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2009). ↩

-

For the relation of white patriarchal rule to fossil fuels, see, e. g., Cara New-Daggett, “Petro-masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire”, Millenium: Journal of International Studies, Volume 47, Issue 1 (2018). ↩

-

For examples where the environmental and workers’ struggles have explicitly conjoined, see, e. g., Stefania Barca, Workers of the Earth: Labour, Ecology and Reproduction in the Age of Climate Change (London: Pluto Press, 2024). ↩

author

Joel Kilpi

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Political Economy of Hospitality

by

Callum Cant,

George Briley

/

Aug. 21, 2024