Judgements on an Inquiry

by

Jamie Woodcock (@jamie_woodcock),

Tanzil Chowdhury

May 12, 2025

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

Conclusion to the collection

inquiry

Judgements on an Inquiry

Conclusion to the collection

Underlying all workers’ inquiries is a practical commitment. The ‘goal is not to understand work, but to inform the struggle against it’.1 The hope is that this collection of essays can serve that function in some small way by helping workers to make sense of their differentiated work places, the abstract domination of their work contracts, and how they may organise, resist, refuse, and care for one another. Readers will be able to draw their own conclusions from this book, but the following are some patterns in legal workplaces that we have identified as significant.

Many things unite our writers and their experience of their workplace. In particular, for many of the writers, their legal practice is oriented around advocating on behalf of those that are exploited, made vulnerable, precarious, and marginalised. In other words, they have deeper political and moral commitments to the areas in which they practice, whether that is in immigration, housing, employment law, or actions against the police. This presents two issues for legal workers. The first is that this capacity for goodwill and political commitment provides a well-worn opportunity for bosses to stretch workers to work long hours or increase the intensity of their work. Marx captures these different strategies of capitalists to increase their surplus value; what he calls absolute (increasing the length of the working day) and relative surplus value (increasing productivity, typically through technological changes). The goodwill and political commitment can be mobilised for either of these strategies. They appear to underwrite both and offer different ways in which bosses can increase the rate of exploitation of their legal workers. The application of these methods represents an important way in which the legal labour process is increasingly subsumed under capital.

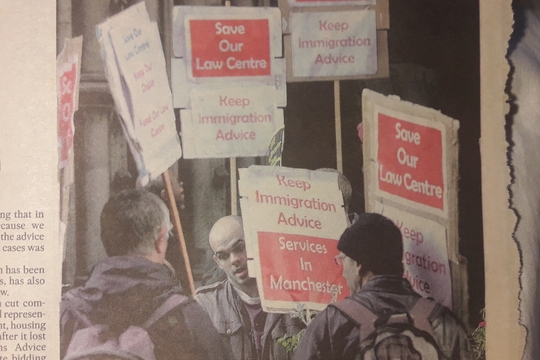

The second is that goodwill and political commitments present many legal workers with a conundrum. As one of our writers Oliver Conway expressed in a discussion with the other authors of this book: withdrawal of labour could have a directly damaging effect on vulnerable people. Legal workers can therefore be faced with a serious moral quandary when withdrawing our labour. This is a challenge that also confronts health and education workers, necessitating a clear strategy communicating the temporalities of worker’s struggle that places the immediate, proximate future (needs of patients/students) within the context of longer-term structural change which benefit all. Indeed, what such a strategy demands is connecting legal service provision to working conditions (such was the refrain of education workers that their ‘working conditions were connected to their students’ learning conditions’). But what does this mean for a client with an impending eviction or deportation order? Khadijah, another of our contributors, mentioned that navigating these issues requires establishing networks and organisations, beyond the Law Society and other professional associations, in which to discuss tactics and strategy.

Another interesting observation from these essays revolves around the perennial challenges in raising worker consciousness among legal workers. In Capital Vol. 1, Marx spends some time describing capital’s organisation of the labour process through co-operation, a way of organising ‘many workers working together side by side in accordance with a plan’ under the authority of the capitalist. But this also contains a contradiction. While it may increase productive power and surplus value for the capitalist, it also brings previously atomised and individualised workers (Marx was also making an historical point about the ‘formal subsumption’ of guild labourers and other labourers that worked at home) together under one roof (what Marx termed ‘real subsumption’) which offers the potential for developing class consciousness and organising. Marx writes, ‘as the number of the co-operating workers increases, so too does their resistance to the domination of capital, and, necessarily, the pressure put by capital to overcome this resistance’.2 Something that Roger Bravo points out however, is that despite working in the same offices, private law firms are highly individualising and competitive workplaces. We might partly attribute this lack of collective consciousness to a rigid hierarchy (especially the partnership models where senior lawyers invest their own capital into the firm), and a clear incentive structure. However, there appears to be something especially distinct about legal practice’s socialisation of its workers as atomised and perhaps even not as ‘workers.’ The problem of this socialisation arguably begins earlier, as Kate Bradley discusses, in legal education.

There are also problems with how we align the interests of different types of legal workers in the legal workplace, from lawyers to paralegals, to support staff and clerks. This is something not unique to the legal workplace, but found across sectors and kinds of work. It is, perhaps, made harder by the question of ‘exceptionalism’ with legal workers, especially those that practice law. One might understand them as functionaries of capitalism, guardians of a form of social regulation that is unique to capitalism. Even in a more charitable reading, legal workers that deliberately orient their practice in the service of the working class are in some ways softening the harsher edges of capitalist immiseration.

One of our writers, John Nicholson, a former immigration barrister, was very frank about not wanting his job to exist. So should we be organising to defend these jobs? In some ways, that might confuse the temporalities of worker struggle, which defends legal worker jobs and better conditions, but can also organise around summoning and building another world. However, if we do not struggle in the here-and-now, there is little prospect of getting to any alternative future. This belief that some legal jobs should not exist is arguably analogous to the discussions around jobs in the arms industry. One response to which has been a return to alternative proposals like the Lucas Plan.3 How might we repurpose the skills of legal workers for other activities?

Many of the writers said they had found great solace in reading the contributions of others. It is through seeing these common patterns of exploitation and degradation, the challenges in workers coming together and organising despite being in different places, that we make sense of what connects their material realities and how they might change it. Given the accounts of legal workers, as well as their attempts to unionise, the need for worker organising is as important now more than ever. This is not just because of deteriorating working conditions, but also because of the huge disruptive potential that organised legal workers could have. They are increasingly connected with other workers. What happens in the legal sector could have important knock on effects for other parts of the class.

So where next after this collection? We hope that it provides a starting point for further discussions about class composition and organising in the legal sector. Although there have been experiments with LSWU within UVW, many of the legal workers have since left the union. As mentioned earlier, over the last year, some legal workers have steadily been moving to instead actively organise within their workplaces under Unite the Union (albeit there remain political disagreements), whilst encouraging other workers to join in the latest foray into organising across the sector. We intend this collection also as a moment of collective reflection about what has worked, what has not, and what steps (small or large) legal workers can take next.

We welcome further responses and reflections that can be published in Notes from Below.

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Introduction to the Legal Workers’ Inquiry

by

Jamie Woodcock,

Tanzil Chowdhury

/

May 12, 2025